Mixed feelings about China’s new river

Kai Ryssdal: The interesting tidbit from the European debt crisis negotiations today goes a little something like this. It’s gotten so bad that French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s been reduced to cold calling, like a bond salesman. Which, come to think of it, is a pretty good description.

Bloomberg News reports Sarkozy’s going to put in a call to Chinese President Hu Jintao to try to talk him into contributing to an expanded European bailout fund.

China, of course, has the money because its economy is growing at 9 percent a year. It’s growing so fast, in fact, that China’s running out of water. Scientists say Beijing and Tianjin — two cities in the north with more than 34 million people between ’em — will run dry within just a couple of decades.

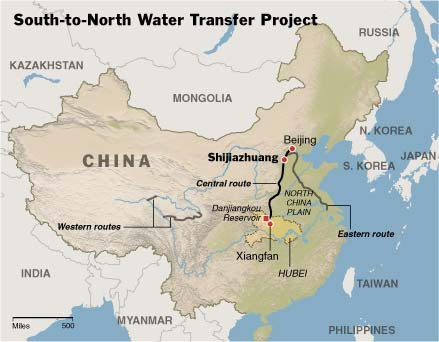

The proposed solution turns out to be the biggest public works project in the world. Our China correspondent Rob Schmitz has the story.

Rob Schmitz: Tens of thousands of workers are constructing what is essentially a concrete river 800 miles long through central China. In three years, China plans to release water from one of its largest reservoirs into this new waterway.

Credit: JapanFocus

Hardly anyone’s questioning whether it will get to Beijing. But China’s top scientists and policy makers are debating whether diverting all this water is worth the potential damage to the environment — and whether it’s wise to spend $62 billion to build a project dreamed up by a dictator who died 35 years ago.

Dai Qing: Mao Zedong’s philosophy was that man can conquer nature. But if you act against nature, you will be punished.

Dai Qing is a former communist party member who’s written books criticizing China’s water policies. She says a big problem is China’s communist party. It’s always been ruled by engineers. Dai happens to be an engineer too.

Qing: Our leaders think that this project is a simple matter of mathematics. It’s much more complicated. How will it impact the environment and climate of the Yangtze River region? That’s a problem that can’t be solved with a calculation by engineers.

Taking water from the Yangtze and carrying it to Beijing is like diverting the Mississippi River to Washington D.C. Some Chinese scientists warn that taking so much water could destroy the ecology of China’s southern rivers. What’s clear is that it’s already taken a toll on the people.

Ji Guimei picks peanuts at her farm in the village of Shilin in Henan province. Three hundred and fifty thousand people have been forced to move from their homes for this project. She and her husband are among the last remaining holdouts.

Ji Guimei: None of my neighbors have moved either. The government wants us to pay a huge sum of money for our new home. We can’t afford it, so we’re staying here.

Ji says the local government has offered the equivalent of a $1,000 for her old home, but has asked them to pay 16 times that for a new one. Ji admits she doesn’t even know anything about the project she’s moving for. Her husband, Sun Bencheng, does, though. He says if the money’s right, he’s willing to move for it too, but it won’t be easy for this 75-year-old farmer.

Sun Bencheng: My family’s lived in this village since the Ming Dynasty. We have a saying here: Neither a silver nor a gold house is better than our own poor house.

The local government official in charge of this area is Xiao Yaodong.

Xiao Yaodong: We don’t consider those villagers migrants. They’re not moving as far as many others are. So we’re not compensating them as much.

But in general, China is giving out more to migrants than it has for past mega-projects, much more than it gave to those who moved for the first phase of this project — a huge reservoir China built in the 1950s.

Author Mei Jie wrote about her family’s relocation back then. She was away at college when her family had to move.

Mei Jie: When I returned home, I couldn’t find the place where I had grown up. It was underwater. I miss my hometown so much. I felt I had to tell the world about the suffering of the people in China’s south so that the people in the north would cherish their water.

But Northern China has been too busy growing to take notice. Now, nearly 200 million people live on the North China Plain — a place where desert gobbles up an area the size of Rhode Island each year.

Back in the southern Henan, a family of pigs sleeps on top of each other in their new home. This is the new village of Jiawa a hundred miles away from where it used to be — a memory that will soon disappear underwater. The new village consists of drab cement buildings painted bright yellow.

Farmer Li Jinrong used to make $5,000 a year in her old village. That’s 25 times more than what she’s made this year. She’s dipping into her savings to afford electricity and running water — luxuries she’s never had before.

With a crooked smile, she recites a popular phrase written on communist propaganda posters throughout China: She Xiao Jia, Wei Da Jia — sacrifice the small family for the big family.

Reporting from Henan province, I’m Rob Schmitz for Marketplace.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.