Discovering hidden languages in centuries-old writing

If you were around during the ’80s, you probably remember the Indiana Jones movies—the swashbuckling archaeologist traveled the world digging up ancient treasures.

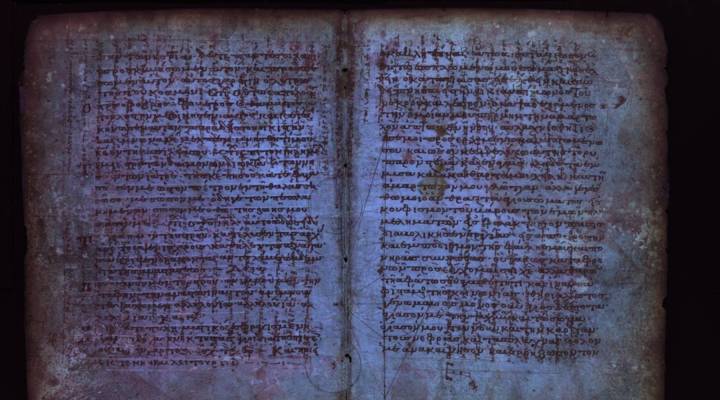

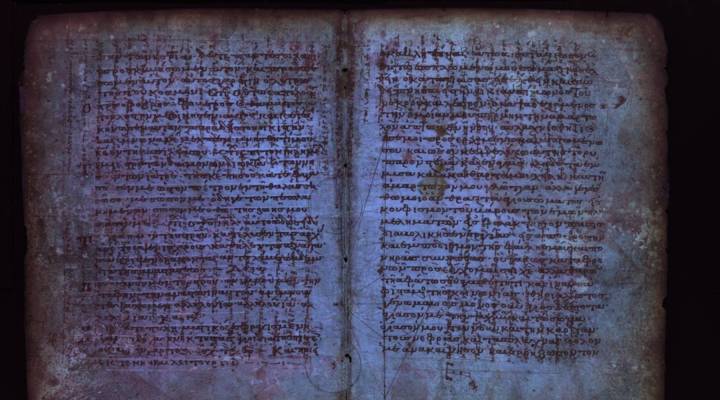

If you were to go looking for a real-life, present-day Indiana Jones, you might get someone like Michael Toth. He travels with his teams around the world using modern technology—lasers, high-tech cameras—to unearth treasure. It’s centuries-old writing that appears in very faint form on manuscripts called palimpsests. Along the way, they’ve discovered everything from lost languages to some very mysterious fingerprints.

You’re not discovering ancient manuscripts; you’re working to read what’s buried in them. Tell me a little about the work you do.

We work on a range of manuscripts—the earliest copy of Archimedes work, David Livingston’s diaries—and we use spectral imaging to reveal that text which is not seen by the naked eye.

Why isn’t that text visible? We’re talking about two different layers of writing here, right?

That is correct. It’s usually on parchment. And they’re written initially with an ink made out of the galls of oak trees, and that’s been scraped off and overwritten. And in doing so, it’s preserved that text underneath it.

And the process you use is something called spectral imaging. Tell me about that and what kind of technology is involved in that.

So we shine lights on the object to bring out that ink which responds best to, say, the ultraviolet in the case of iron gall, or a modern carbon black ink in the infrared.

You and I met in the Sinai Desert, when you were working at Saint Catherine’s Monastery to look at some of the ancient manuscripts that have been held in the library there for over 1,000 years. Tell me a little about the work you’ve done at Saint Catherine’s and some of the things you found.

Some are historical texts. Some are medical or mathematical texts. We’re still assessing what is underneath this rich trove and, ultimately, are going to make this available to the world.

Do you have a favorite moment of discovery?

Oh, yes. The work on Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Gettysburg Address. And as we were imaging it, at the bottom, on a blank part of the paper, the ultraviolet light came on and there’s gemlike glow at the bottom. And we said, “Hey, we’ve gotta look at this,” and we saw a thumbprint. And then on the back three fingerprints. As if someone was holding that paper, which is folded in thirds, as if it’s in a coat pocket, had held it up to read.

And is it Abraham Lincoln’s fingerprints?

We don’t know. We know there’s enough of the whorls and loops to be able to assess the fingerprint. But of course there was no FBI fingerprint lab, much less West Virginia back then. So they are working with various forensics experts to try to assess that compared to other documents.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.