San Francisco area voters pave the way for climate adaptation

San Francisco area voters pave the way for climate adaptation

Climate change has largely been ignored in conversations surrounding the presidential election. Local elections have been another matter, however, with many cities and states talking about how to deal with it.

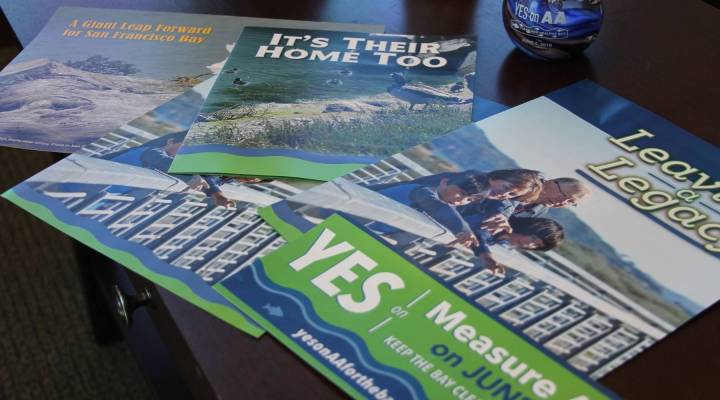

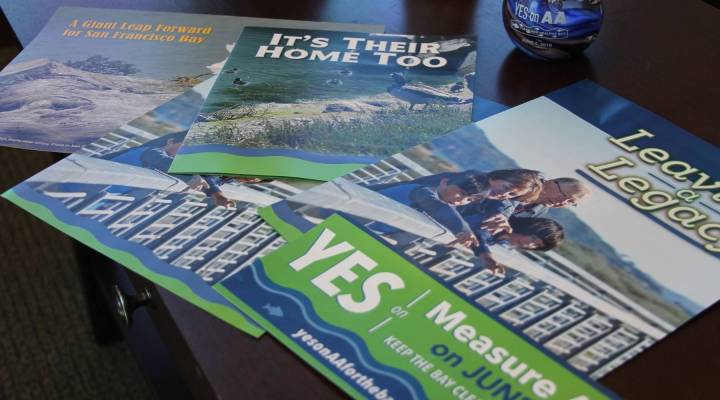

Last June, San Francisco area voters took a major step in adapting to sea level rise by approving a Measure AA, a $1-a-month parcel tax that will raise $500 million over 20 years, with the purpose of funding wetlands restoration.

Because of state requirements, the measure needed to secure 66 percent of votes in order to pass. Such a majority can be difficult because many object to parcel taxes, since single family homeowners pay the same amount as, say, Google. It got 70 percent.

David Lewis, executive director of Save the Bay, which spearheaded the funding effort, said part of the reason the measure got so much of the vote was there’s so much love for the bay.

“When you say San Francisco Bay you’re saying the Bay Area, and Measure AA — which is a very small tax shared by a lot of people to raise a lot of money together for a big benefit — that felt like doing something for the place we live,” Lewis said.

David Lewis, executive director of Save the Bay, stands in his office in downtown Oakland. His organization spearheaded the effort behind Measure AA.

Environmentalists have long touted the benefits of healthy wetlands: cleaner water, habitat for species and carbon sequestration. These days, however, more focus is put on their ability to slow storm fronts and absorb flood waters.

“The business community here has come to realize that part of the solution for addressing climate change and adapting to sea level rise in the Bay Area is restoring wetlands where we can do that,” Lewis said.

Estimates for the Bay Area put the financial costs of higher sea levels at tens of billions of dollars by century’s end. Spots on Highway 101 along the bay see more than 100,000 vehicles each day. At Google’s headquarters, some buildings lie within a 1,000 feet of the shore. Meanwhile, people keep building on the bayfront.

Restoring wetlands is a strategy to adapt to the higher sea levels and increased flooding associated with climate change. On a recent Wednesday, San Mateo County Supervisor Dave Pine was touring Bair Island, the site of a restored salt pond.

Trail signs along the boardwalk discussed the return of animals such as the leopard shark.

Dave Pine, chair of the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority, observes the restored Bair Island.

“As the bay ecosystem improves, more and more species are coming back,” said Pine, who is also chair of the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority.

As important as the habitat is for animals, it also serves the humans whose housing is being built right next door.

“Tidal wetlands provide natural flood protection for the bay shore, so by restoring these wetlands, we can help protect communities from storm events and from sea level rise, which is a reality we have to face,” Pine said.

Lewis said the eventual goal — if enough money can be raised — is to restore 100,000 acres of wetlands to keep the bay’s ecology healthy while putting a natural buffer between the ocean and development. He estimated the effort could cost $2 billion.

The plan is to leverage Measure AA’s $500 million to get federal and state grants. Depending on how things go from here, other areas could follow, restoration advocates said.

“Now that there is an example of this out there that was successful, I think that there are other candidate areas throughout the country, be it Chesapeake Bay, Galveston Bay, Tampa Bay — there would be the opportunity for others to sort of emulate this,” said Allison Colden, Senior Manager of External Affairs at Restore America’s Estuaries.

Actually emulating the regional funding strategy would require appreciating the sheer amount of planning that went into the effort. Measure AA was in the works for 13 years, giving organizers a lot of time to build support among the bay’s counties and cities, community groups and businesses.

Lewis said they performed extensive polling and waited until after the recession to make the push. He said it was also a matter of picking the right election.

“One of the one of the smart choices was to put this on the June ballot when there wasn’t a lot of competition for people’s attention,” Lewis said.

Kristina Hill, a professor of landscape architecture and environmental planning at University of California, Berkeley, said similar ballot measures will pretty much be a must for major adaptation projects to happen elsewhere.

“Who else is going to pay for it?” she said. “The federal government only bails us out when we have a disaster. So if we’re talking about adaptation rather than resilience to a disaster event, we have to figure out how to use our tax bases to pay for these things.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.