Why clothing sizes are all over the map

Why clothing sizes are all over the map

Listener Caren Johannes of Westminster, Colorado, emailed this question to Marketplace: “I’ve always wondered how clothing manufacturers figure out what sizes of clothes to make. I’m very short and I have a terrible time finding clothes, as do many of my relatives and friends.”

This is a common experience, according to sociologist Amanda Czerniawski at Temple University. “Clothing sizes make no sense and they never have,” said Czerniawski, who recently took a deep dive into the fashion industry and published a book about her experiences: “Fashioning Fat: Inside Plus-Size Modeling.”

Czerniawski pointed out that until the early 1900’s, most people made their own clothes, or if they were rich enough, had a tailor or dressmaker do it for them. By the mid-20th-century, though, most people were buying “ready-to-wear” clothing mass-produced in modern textile mills. It was marketed to the growing middle class, sold at department stores and from mail-order catalogs.

During World War II, said Czerniawski, “the U.S. government was interested in standardizing sizing to conserve fabric.” The booming catalogue industry wanted size-standardization as well, she said. “It was costing them about $10 million a year not to have set sizes,” because so many people returned missized, ill-fitting clothing that they’d ordered.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which then had a Bureau of Home Economics, hired statisticians to analyze the body measurements of thousands of American women, and in 1958 issued the first standardized women’s size guidelines for the apparel market.

By the 1980’s, though, brands had largely abandoned the standards and developed their own. As a result, different brands of clothing that are marked with the same size, can vary by as much as three to four inches.

And Czerniawski said major apparel brands actually like having their own sizes: “Part of the reason is that it forges brand loyalty. If you find a pair of pants that fits you well, you’re going to continue buying from that same brand.”

Brands also exploit consumer psychology in sizing, said Tasha Lewis, an assistant professor of apparel design at Cornell University, by adjusting their sizes to make female customers feel thinner.

“Vanity sizing is very real,” said Lewis. “I worked at one company — and to make a customer who wore a size-2 feel like she wore a size-0, they shifted all the measurements down.”

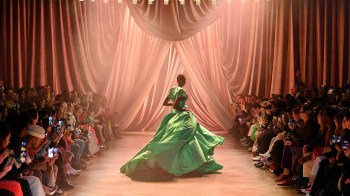

Lewis said that some brands won’t even make designs to fit bigger women — in the plus-size range — because they want to be associated with a “skinnier” image. “So if you’re not that size — a celebrity on the red carpet, maybe — they don’t have a sample for you to wear,” she said.

Big changes, driven by new technology, are on the horizon for the industry. New apparel startups are experimenting with the use of 3-D scanners and smartphone apps to take an individual customer’s precise body measurements, send the data to a small-batch textile factory, and custom-produce a garment sized to fit. Whether this can be done at an affordable cost, at sufficient scale to serve the mass-market, remains to be seen.

Read more from Marketplace’s series “I’ve Always Wondered…” here.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.