The Cassini mission has ended, but its legacy remains

At 7:55 a.m. EST on Friday, September 15, NASA scientists at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, received the final whisper of data from the Cassini spacecraft as it entered Saturn’s atmosphere. Called “the plunge,” this marked the end of Cassini’s 20-year career, with 13 years spent in orbit around Saturn.

“Cassini completely blew our minds,” said Jim Green, the director of Planetary Science at NASA. Green spoke to Marketplace Weekend host Lizzie O’Leary just before Cassini’s final moments.

For Green, and the over 250 people who worked on Cassini, the images and data captured by the spacecraft were a revelation. Much of what we know about Saturn and it’s many satellites came from Cassini.

“The observations that are being made by Cassini tells us much more about the moons and how they could potentially harbor life,” Green said. “This is just tremendously exciting. It was really unexpected, and it really took the Cassini spacecraft to uncover that.”

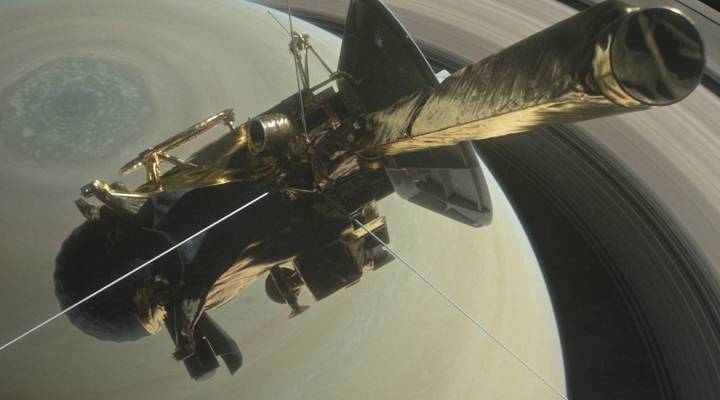

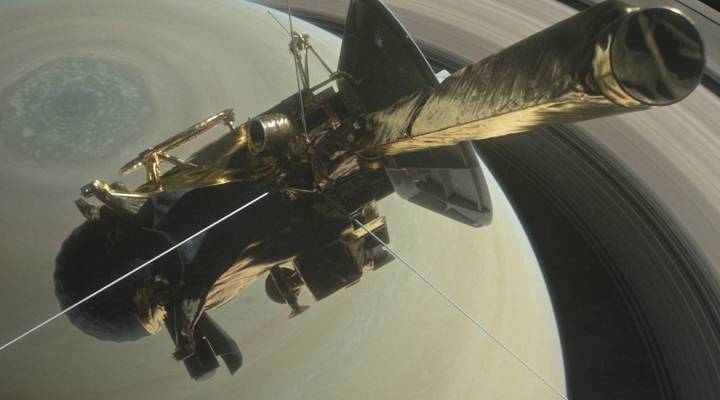

One of Cassini’s final images, taken of Saturn’s rings.

“Cassini is sending our people into the unknown”

For the team behind Cassini, the end of a two decade-long mission is the end of an era. While some have moved on to other missions, others may not do so — and may not want to.

“You know, we’ve sent Cassini into the unknown and it is really surprised us,” Green said. “And now with the death of Cassini, you know, with its plunge, Cassini is sending our people into the unknown. What will they do next?”

While the future is uncertain, working on Cassini has made these people incredibly valuable; according to Green, they understand how to plan orbital missions, and have come up with new ways to measure data gathered in these missions.

“Cassini has developed a workforce that is just so important to planetary science,” Green said.

Jim Green, Director of Planetary Science at NASA, speaks at NASA HQ on September 24, 2009.

Space isn’t cheap — but the tech may be our future

Supporting that staff is only one of many costs that a mission like Cassini incurs. According to NASA, Cassini cost about $3.26 billion over it’s lifespan — and almost half of that was spent before it even launched.

“You know, operationally, Cassini was running around $50 million per year,” Green said. “And so you can see that the major cost is really the upfront development, and the mission building. And then, of course, the launch.”

Yet, the high cost to the taxpayer doesn’t intimidate Green because space exploration tends to pay back in dividends. The data and tech developed for space exploration often finds other uses — like monitoring climate change. In fact, NASA is the reason we understand the primary mechanism of climate change in the first place.

It started, not on Earth, but on Venus

“We’ve applied to Earth some of the original research on why doesn’t Venus have much of an ozone,” Green said. “We spent time and research and discovered that it was the chlorine.”

“And then, we found in the 80s that the earth was losing its ozone. [Climate researchers] turned immediately to research that was done by planetary scientists and recognized that the culprit, once again, is chlorine, and it’s coming from CFC [chlorofluorocarbon gas].”

Green isn’t worried about funding further planetary missions — at least for now. In May, NASA received its highest budget boost in years, and the planetary division received about a $1.86 billion increase.

For Green, investing in planetology is much more than mere exploration. The applications we learn from studying other planets can help us understand what could happen to Earth.

“I firmly believe the survival of our species depends on us doing that,” Green said.

“Human exploration is not ‘Star Trek’”

For his next destination, Green is looking a planet that is little closer to Earth: Mars. Based on our current level of knowledge about the planet, he thinks we could send humans there within the next several decades.

“Human exploration is not ‘Star Trek,’” Green said. “It’s not, ‘Go where no human has gone before.’ And so, that means before humans go to Mars, we must really understand that environment.”

As a planetary scientist, Green’s role won’t be to send humans to Mars, but to gather all the necessary data about Mars beforehand. One of his projects? Figuring out where people could potentially land.

“We are the pioneers. We’re leading the way,” Green said.

Above is a livestream of Cassini’s final moments, filmed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA. Courtesy of NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory

| How to get to space without NASA |

| What Trump’s presidency could mean for U.S. strategies in space |

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.