Changing the way we measure inflation could boost Social Security benefits

Changing the way we measure inflation could boost Social Security benefits

Florence Carlson moved to Florida 13 years ago with her husband. They were both Social Security beneficiaries.

“When he died 15 months later,” Carlson said, “I continued to take his Social Security, which was slightly more than one, I guess, at the time. And it probably was very little less than what I’m getting now, because, as you know, through the years, Social Security has not kept up with the cost of living.”

Carlson lives in a senior community, which she likes, but it isn’t cheap. She has to pay for internet, car insurance, homeowner’s insurance and her groceries. Her Social Security benefits don’t cover all of her expenses.

“I get about $1,150 a month,” Carlson said. She estimates that she receives about $14,000 a year, and her expenses are around $60,000. To pay most of her bills, Carlson has to dip into her savings.

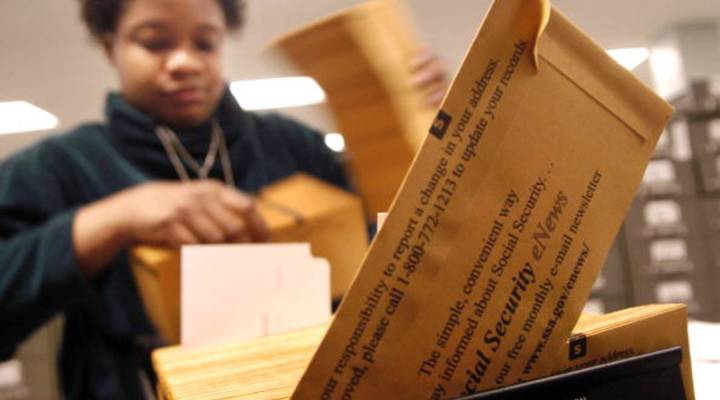

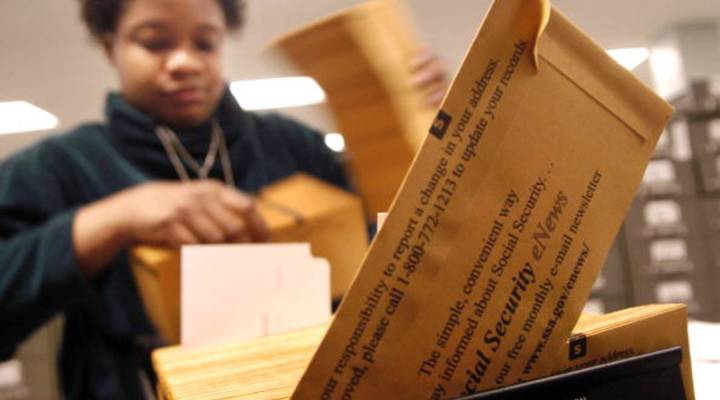

So how did the Social Security Administration come up with the number “$1,150,” anyway? Every October, the SSA calculates the cost of living adjustment, or COLA, to counteract inflation. And the way it calculates inflation is by using a measure called the Consumer Price Index for Clerical Workers and Wage Earners. The CPI-W takes a basket of goods and asks, all right, how much would someone who’s working pay for these goods?

“That really is where the issue about whether it’s appropriate for Social Security beneficiaries comes in,” said Gary Koenig, an economist with AARP. “Because the basket of goods that is made up of the CPI is reflective of the consumption patterns of workers and not retirees.”

Koenig said the CPI-W doesn’t take into account the things that Social Security beneficiaries are more likely to buy, like prescription drugs. Instead, he advocates for a different measure, one that focuses specifically on the needs of retirees. It’s called, appropriately, the Experimental Consumer Price Index for the Elderly. It also has a nickname: CPI-E.

| Six expert secrets to a successful Social Security strategy |

| With breach after breach, why are our Social Security numbers tied to everything? |

“If you look at someone who receives Social Security benefits for, let’s say, 20 years, moving to an index that is more reflective of the purchasing power of older Americans, like the CPI-E, would translate into about a 4 percent higher benefit than they would under the current COLA,” Koenig said.

While this sounds great on paper, it’s also a tough sell. The Social Security Trust Fund will run out by 2034 — there will still be money coming in, but not enough to pay out the benefits people are used to. Some economists see measures like the CPI-E as a little irresponsible, given the forecast for Social Security. Then there’s the fact that CPI-E is still “experimental.”

“[The Department of Labor Statistics] is clear that it is not a fully baked, official measure of inflation,” said Andrew Biggs, a conservative economist at the American Enterprise Institute. “There are other measures of inflation, including what’s called the chain-weighted CPI, that is superior in the sense that they better account for how people change their purchasing habits in response to changing prices.”

For Biggs, the CPI-E is just a benefits increase that hasn’t been fully thought out. For example, if one drug becomes more expensive, than someone might just switch to a cheaper brand. The CPI-E doesn’t measure this, and for Biggs, that’s a significant oversight.

What matters to Florence Carlson is that Social Security isn’t making her feel more secure under the current system.

“I feel as though my money is just diminishing monthly,” Carlson said. “I just continually have to draw on whatever capital I have left. And if I don’t live too much longer, than that I’ll be fine. But if I do, I actually could run out of money, probably in, I don’t know, maybe five to six years. Certainly I can’t think of anybody who could live on Social Security.”

If you want share your story about living on Social Security or how you’d change it, get in touch! You can leave a comment here or email us at weekend@marketplace.org.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.