Barriers to homeownership still exist for people of color

Racial discrimination in the home loan industry used to be explicit and legal: Redlining indicated neighborhoods where African-Americans and other people of color lived, and encouraged banks not to lend there. Now it looks a bit different. Aaron Glantz, a reporter at Reveal, from the Center for Investigative Reporting, talked with Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal about his new piece, “Kept Out,” exploring how redlining lives on in this economy (you can listen to the podcast this weekend). The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: There was an amazing story in this piece. A woman of color goes to apply for a mortgage to buy a house. She’s working at a university at a good job. She can’t get the loan until her partner, who is working at a grocery store for $145 every three weeks or something, co-signs the loan. And of course, the partner is half-white, half-Japanese.

Aaron Glantz: Yes, one of the people we interviewed for this story, Rachelle Faroul, spent two years trying to get a mortgage. First, she was teaching computer coding at a university. She was turned down because she was a contractor. So she went and got a job managing a million dollar grant at an Ivy League college and went back, tried to get a mortgage again. Got turned down again. Eventually, she said, well what if I bring on my partner? And her partner was half-white, half-Japanese and her most recent paycheck was for $144. And the lender said, OK, now we can go for it now. Now this is good to go. Now you can buy the house.

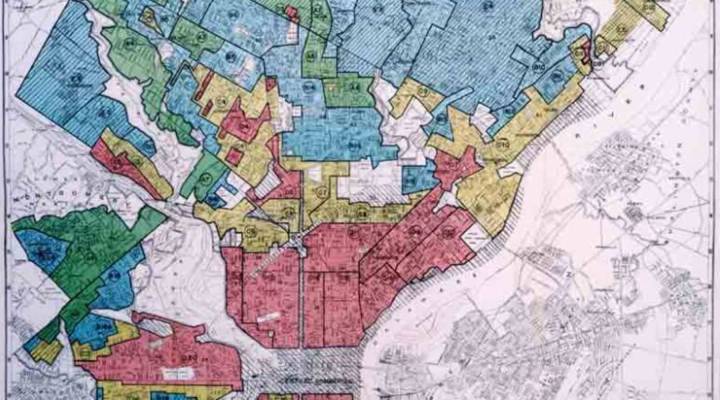

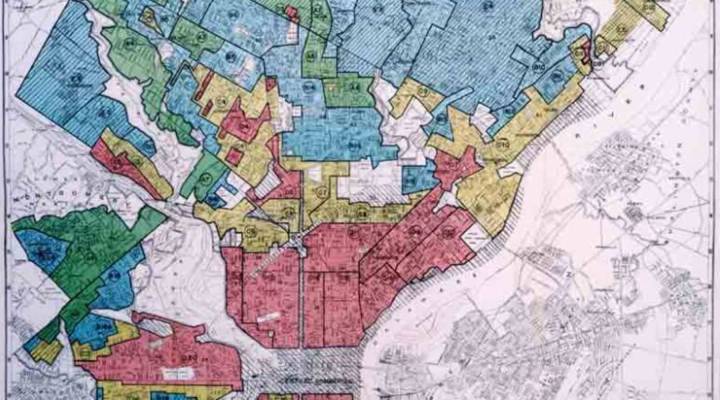

Ryssdal: There is an urban decay part of this story as well, and that is that redlining, when it went into effect in the ’30s, excluded a lot of those areas from development, and the relic of that development, the lack of investment, continues to this day. And you can see it when you go around to cities in this country.

Glantz: So back in the 1930s, the government literally drew lines on maps, identified the neighborhoods with large numbers of African-Americans or immigrants, colored them in red and said they were hazardous and that banks should not lend there. Even after discrimination was banned, banks were still not lending in these communities. So in 1977, Congress came back again and Jimmy Carter signed the Community Reinvestment Act. And it said banks have an affirmative obligation. They have to try to lend in these communities. What we found in our investigation is despite this pervasive disparity across the country that 99 percent of banks are getting a satisfactory or outstanding rating from the federal banking regulators who enforce this law.

Ryssdal: Well, what do they say? What do the regulators say and what do the banks say when you go to them and say what?

Glantz: The regulators say that no bank is forced to make any particular loan, and you have to look at the underwriting. And, of course, we don’t have the access to the underwriting on every particular loan. But it doesn’t make any sense. Are you telling me that on a systemic basis black people and white people who make the same amount of money that the white people on a systemic basis are more creditworthy? Maybe there’s something wrong here. But there’s another aspect to it, which is that this law — the Community Reinvestment Act — did not foresee a lot of the urban dynamics that we have today. I mean, they were worried about urban blight, and the whole phenomenon of gentrification that we’re seeing now, it just didn’t exist. And one of the things that we found in our reporting is that there are a lot of neighborhoods where banks are making a ton of loans to white newcomers at the same time that they’re denying a large proportion of people of color who want to buy or refinance or get a home improvement loan to stay in that same neighborhood.

Ryssdal: One of the things we haven’t talked about is the more big-picture socioeconomic thing, which is one of the ways you build individual wealth in this economy is by home ownership. And part of the reason that there’s such a gap in black and white wealth in this country is because blacks have been excluded from buying homes, in part because of redlining like this.

Glantz: Right. So today, according to the Census Bureau, the average white family is worth about 15 times the average black one. Fifteen times. And a lot of that has to do with the homeownership gap that we talked about earlier. That the homeownership gap in America today is wider than it was when segregation was legal and discrimination was legal. Our investigation found that in 61 cities across America — Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Detroit, Chico, California — that in all of these places, even when you control for income and the size of the loan and the neighborhood that somebody wants to buy in, that people of color are more likely to be turned away. And then we turn and we say, “Well, we have this huge racial wealth gap. Are these two things connected?” You tell me.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.