With international student enrollment declining in the U.S., intensive English programs feel the pinch

With international student enrollment declining in the U.S., intensive English programs feel the pinch

Ali Ashkanani started studying English in elementary school in Kuwait, more than 6,000 miles away from where he now lives in Philadelphia.

He said he realized quickly that the English pronunciation he learned in Kuwait wasn’t going to cut it, if he was going to pursues a degree in industrial engineering in the United States.

Take the common phrase — “bottle of water.”

“In our country we say, ‘bottle of water,’ ” he said, shortening the vowels and pronouncing a hard ‘t’ in both words. “But here, you should say ‘boddle of wooder,’ ” he said, mimicking the confident slur of a native English speaker. To bridge those gaps, Ashkanani, 19, began an intensive English program at Temple University last fall. Each 14-week session costs about $5,800.

During the 2016-2017 school year, more than a million students from abroad came to take higher education courses in the United States, injecting nearly $40 billion into the economy, according to Open Doors, a group that tracks international student enrollment for the U.S. Department of State.

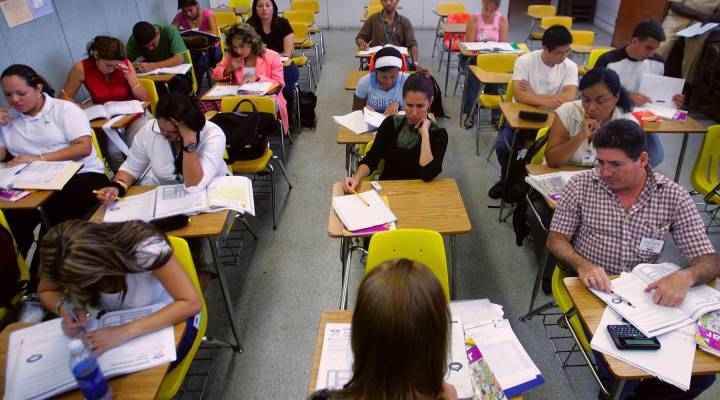

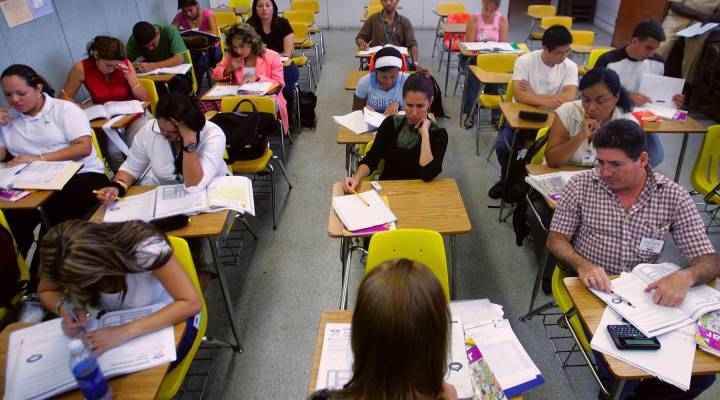

In many cases, those students need to perfect their English before moving into a degree-granting program, leading to a boom in intensive English language programs in recent years. These programs provide international students with full-time English language instruction, geared at getting them through English language placement tests and into college in the United States. After a period of rapid growth, those programs and the teaching jobs they support have declined sharply in the last couple of years.

Ann Draemel, Ashkanani’s instructor in Advanced Listening and Speaking 1, said when she first started working at Temple in 2013, many of her classes had more than 20 students. Now, the smallest has fewer than 10 students.

“It makes the classes interesting. I kind of prefer them to be smaller, but it’s also a little bit alarming,” Draemel said.

That story — of intensive English language classes shrinking by half — repeats itself around the country.

“Language programs, the majority of them, are experiencing decreases in enrollment,” said Cheryl Delk-Le Good, executive director of EnglishUSA, a trade association for intensive English programs. Overall enrollment in intensive English language programs declined by 26 percent in the 2016-2017 school year — the second consecutive year with a large drop. At the same time, total new international student enrollment in the U.S. declined by more than 3 percent, the first such decline in more than a decade, according to Open Doors.

Enrollment in intensive English programs can be an omen — for good or bad — of what’s coming in overall international student enrollment, according to Delk-Le Good. She said a combination of factors have contributed to the recent downturn.

“The dollar is so strong right now in the States … it makes it much more expensive to come,” Delk-Le Good said. English programs in other English-speaking countries, such as Australia and Canada, are more affordable — and perhaps more attractive — as a result.

Countries including Saudi Arabia and Brazil, which had been spending big on scholarships for their students to study abroad, have also cut back in recent years.

There was kind of a “bubble” driven by those scholarships, said Jack Sullivan, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s English Language Programs. At the peak of enrollment, around 2014, “we fought for more teachers and more classrooms, more teachers, more classrooms,” he said.

Taken together, these factors paint a bleak picture for Americans who teach international students. Down from a peak of more than 20 guest lecturers a few years ago, Drexel’s program has largely stopped hiring adjunct faculty, according to Heitner. Temple also reduced its staffing levels, while Sullivan said Penn has not replaced staff who have left.

To cope with changing demand, some schools are adding new courses. “We’re shifting our focus to look at other types of programming where we’re seeing an increase in demand,” said Jacqueline McCafferty, the director of Temple University’s Intensive English Language Program. The university is expanding what are called conditional admission programs, which feed students directly from English classes into undergraduate or graduate degree programs.

As for students already enrolled in intensive English language programs in the U.S., they said they have no qualms about their decision. Ashkenani said he’s jazzed about how much English he’s learned in a short period of time.

“The first few weeks I understood nothing in the classes,” he said. “But now, I really love it. I have no problem to stay here for 10 years, until I go back to my country.” Learning English in the U.S. and earning an American degree will make him more competitive in the Kuwaiti job market, he said.

His classmate Abeer Alharbi, 26, wants to earn a master’s degree in pharmacology before returning to Saudi Arabia to work. Like a lot of American students who go abroad, she said coming here was as much about learning a new culture as going to school.

“When I came here, it’s like all the world in one place,” she said. “There’s a real diversity here, and I like that.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.