Exploring the link between housing and health

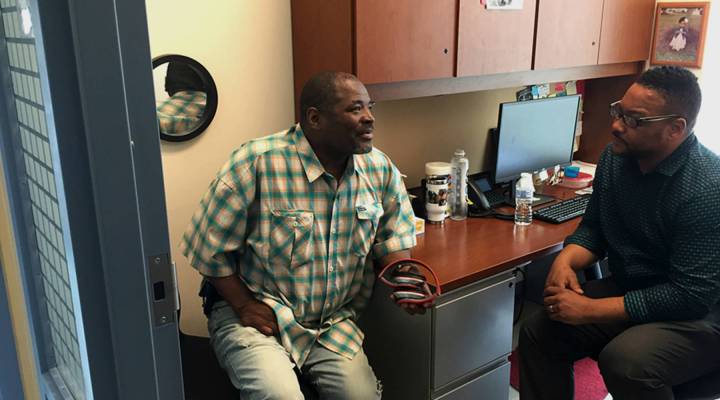

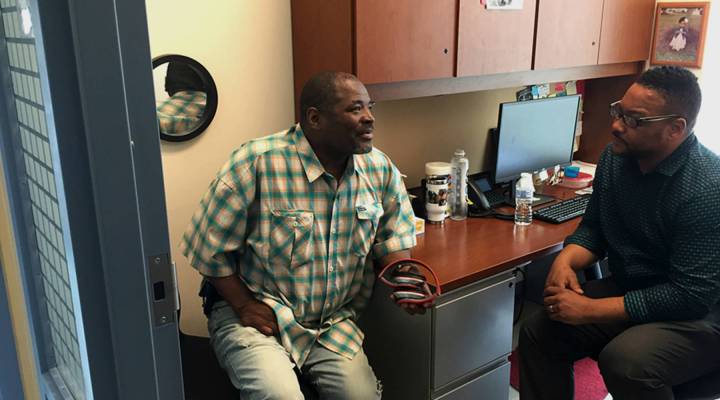

Sidney Bond had been homeless for five years, living between shelters and friends’ couches, when he got a call with good news. He’d gotten off a wait list to move into his own subsidized apartment.

“I’m glad he didn’t see me, because I was running down the street,” he recalled. “I almost tripped on my face because I was so happy.”

The call was from Health Care for the Homeless. As the name implies, the nonprofit group provides medical care to homeless people, at a clinic in downtown Baltimore. It also connects many of them with what’s called permanent supportive housing — a subsidized place to live, plus counseling and other social services.

When Bond was on the street, he said, his chronic asthma and high blood pressure would flare up. He also suffered from anxiety and depression.

“Being homeless can put a strain on a person’s mind,” he said. “I was constantly worried.”

Now, at 54 years old, Bond has been living in his own apartment for more than two years.

“I keep track of my medication, I go to my doctors’ appointments, I see my psychiatrist, I see my therapist,” he said. “It helps me to take better care of myself.”

More health care organizations are making that connection between housing and health. Hospitals subsidize apartments for the homeless in Chicago, Orlando and Portland. Insurer United Healthcare has invested millions of dollars in affordable housing projects in Michigan and Wisconsin. And last month Kaiser Permanente, the health care and insurance giant, announced a $200 million investment in affordable housing.

“The real significance is you’ve got a major corporation saying it’s within our business interests to recognize this relationship,” said Kevin Lindamood, CEO of Health Care for the Homeless in Maryland. “We are confident that that kind of thinking will catch on.”

Several studies have shown the economic benefit of supportive housing, for example a program in Los Angeles saved the county 20 percent on medical and social services for those who got housing, after factoring in the cost of the program.

Kaiser plans to focus not only on providing supportive housing for the homeless, but also on preventing the displacement of lower- and middle-income households. Rising rents have forced families to spend a larger share of their incomes on housing, said Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

“Over half of poor households pay more than half their income for rent,” she said. “That leaves very little for everything else. People can’t get healthy food, they can’t access health care as readily, they’re stressed, and all those result in poor health.”

Just building more affordable units isn’t enough, said Nathan Thomas, a peer recovery specialist at Health Care for the Homeless. “The majority of the work, I believe, is keeping someone housed,” he said. Many homeless people have mental health issues or disabilities that make it hard to live independently, he explained. Thomas helps clients like Sidney Bond navigate those challenges.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as a text: ‘How are you?’” he said. “A lot of times our clients don’t have anybody but us.”

| LA seeks permanent solution to homeless encampments |

| As developers eye valuable mobile park home land, some residents have found a way to fight back |

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.