As 70 mm film sees a comeback, who’s running those projectors?

As 70 mm film sees a comeback, who’s running those projectors?

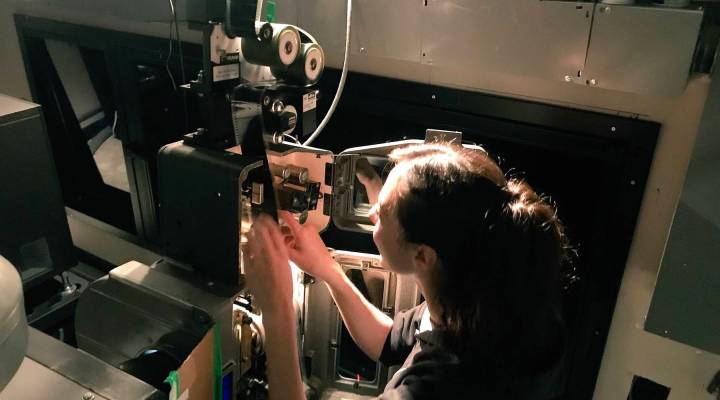

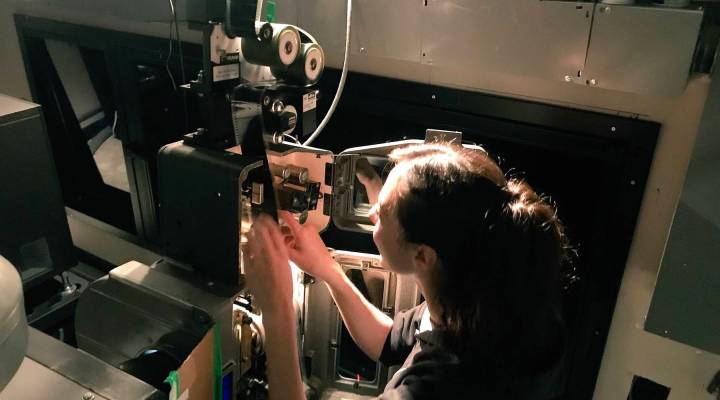

Up in the projection booth at the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Brooklyn, head projectionist Tanner Agle tinkers with a 70 mm projector.

“I’m hitting this green button start,” he said, as the projector starts up a familiar whirring sound. “I’m just gonna run this a little bit.”

He’s leading a training on the theater’s 70 mm projector. It’s a one-on-one lesson on how to thread 70 mm film through hanging rollers, get film to and from the projector without tangling and, importantly, how to time the projector’s startup to seamlessly begin the film after the theater’s in-house “turn your cell phone off” announcement. This 70 mm film is thick — twice the size of typical 35 mm film — and means more color, more detail, more everything on the screen.

Over the past few years, a string of high-profile directors, including Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson and Steven Spielberg, have spearheaded a resurgence of the medium. Films ranging from the Academy Award-winning “Dunkirk” to popcorn flicks like “Wonder Woman” have been released on 70 mm. But a resurgence in 70 mm’s mainstream popularity comes just as the ranks of film projectionists is as depleted as it’s ever been.

In the past five years alone, 12 major blockbuster films have been released in 70 mm. So for people like Agle staffing up movie theaters, it’s led to a need for projectionists who know how to work with the format.

“It is a little hard finding people that are capable,” Agle said. “I do find that now there’s an excess of people who want to work in projection, but there’s not many people who have touched a projector before.”

Two years ago, Agle’s theater screened no 70 mm films. This year, they’ll do seven — and a projectionist needs to be at every screening.

Agle’s teaching Genevieve Havemeyer-King, an archivist at the New York Public Library by day and arthouse projectionist by night, how to use the 70 mm equipment. Havemeyer-King’s been projecting film since 2011 — just not 70 mm film. Recently, she’s been getting calls from theaters asking if she could.

“I get so many calls to run film in New York City because it seems like there’s a shortage,” she said.

So, why the surge in 70 mm’s popularity? Agle, the head projectionist, said it’s a back-to-basics approach after an explosion of digital filmmaking.

“I do think it’s comparable to seeing an HD, 4K picture of the Mona Lisa and seeing it in person,” Agle said. “And seeing the brushstrokes.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, 70 mm film had its first huge splash. Hollywood was competing with TV for attention and cash. Studios began to release bright 70 mm epics like “Ben Hur,” “Lawrence of Arabia” and “The Sound of Music.”

“The sound is going to be amazing, the picture is going to be huge,” said Wade Major, a Los Angeles film critic. “I’m going to get a really theatrical experience.”

An experience, studios hoped, families would be willing to leave the house and pay for.

Today, Hollywood’s fighting a similar economic battle, this time against Netflix and YouTube. Directors again hope 70 mm films will be seen as something you can’t get at home.

But Major said, “You have to have a projectionist who’s schooled in being able to thread them up, treat the prints accordingly. That’s institutional knowledge that’s faded over the last 25 to 30 years.”

The average projectionist is 36 years old today, according to the American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census. No colleges or trade schools offer a degree in film projection. Potential projectionists generally find someone to teach them the ropes.

A few days after her 70 mm training at the Alamo Drafthouse, Havemeyer-King said she hopes to master the craft.

“It’s definitely a labor of love,” she said. “I don’t do this for the money.”

Today, most of the films projectionists work with are digital. That makes the trade vulnerable to automation. Almost a third all projection jobs, digital or film, have disappeared since 2015. One in 10 of the remaining jobs are expected to disappear in the next decade.

“I want film to survive, and I want people to be able to see film,” Havemeyer-King said.

She might get her wish from the projection booth — 70 mm film, one of the industry’s oldest mediums, could be the savior for some of those projection jobs.

“I want it to become normal, I would prefer it to not be, like, too gimmicky,” Havemeye-King said. “I feel like gimmicks die off.”

Ultimately, it’ll be up to whether consumers continue to pay to see 70 mm films.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.