Who owns the results of genetic testing?

Who owns the results of genetic testing?

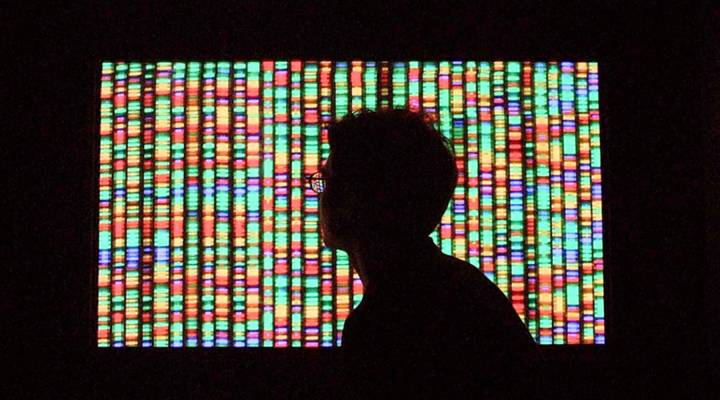

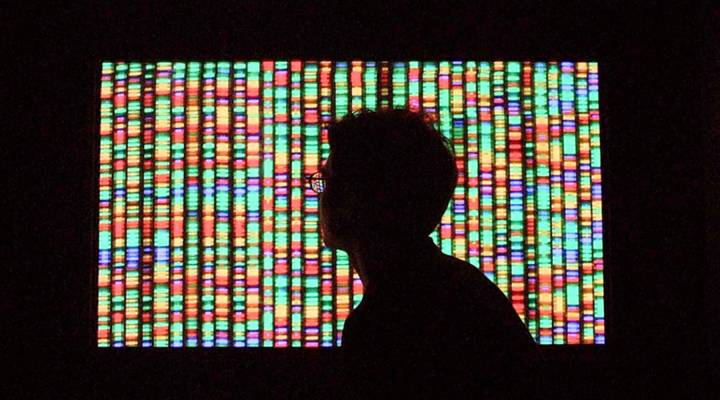

DNA and genetic testing are big business. But there are real questions about privacy and about what happens to your genetic information after you get tested. Recently the DNA testing company 23andMe partnered with pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline to develop personalized drugs and research treatment for diseases like lupus and Parkinson’s. Jen King, director of consumer privacy at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School, told Molly Wood that, surprisingly, most people who take DNA tests don’t think the data is all that personal. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Jen King: Most of them felt that their genetic data, while it was personal, at the same time it didn’t reveal who they really were. One of the other things in my study I looked at was search queries, so when people type a search term into Google, for example, did they consider that more personal than their genetic data? In some cases they did because it really revealed something more about what made them tick, what they were concerned about, what they thought about, what they cared about, whereas their genetic data doesn’t tell you anything about that.

Molly Wood: But then you get the news that 23andMe is partnering with a pharmaceutical company to develop drugs based on the DNA data that they got from 23andMe. Do you think that changes the calculation for people?

King: I think it can because one of the things I discovered is while people were motivated by the idea that their data could be doing good, that often wasn’t very critical. People hadn’t spent time to really dig into what that meant. And so while there’s probably an assumption that, “Well, you know, I’m going to help make a drug that could help a disease I know nothing about and maybe I’ll benefit because I have that disease,” no one, at least of the people I talked to, really sat down and thought about, “Well, wait a second, the company isn’t obligated to give that drug away for free.” They can charge as much as they want for it. So there was this sense of “Yeah, I’m helping the public,” but it wasn’t very critical and really wasn’t carefully thought through just exactly how that might happen, it was more of a check the box, going, “Yay, I can do something good.”

Wood: This is a little sci-fi, I know. As we are also exploring gene editing, is there an argument that we should start to consider patenting our gene profiles? Should we start having an ownership conversation about our most basic identity?

King: That’s a really interesting question. If you look at the customer agreements of these different online genetic testing companies, it’s kind of a big open question as to who owns your data. And the agreements today I think are pretty clear that at least with 23andMe that, you know, once they do something with that data, in this case, partner with a pharmaceutical company and develop a drug on its basis, you sign an agreement saying you have no rights to it, or you have no property interest in the outcome of it, so you can’t go to them later and say, “Hey you need to compensate me for this blockbuster drug that you developed using my data.”

And now for some related links:

- Even though the future of the International Space Station is currently sort of in doubt after a Soyuz rocket malfunctioned last week and two astronauts barely survived, NASA is trying to figure out when it can send astronauts to the ISS again. They’re also trying to decide whether the ones who are already there will have to abandon the space station completely for a while. The Russian rockets are currently the only way to get humans to and from the ISS, and they’re grounded because of the accident.

- Jeff Bezos’s aerospace company, Blue Origin, put up a video today, promising to send millions of people to space. And look, I’m not trying to be down on big ambitions. But we seem to be doing a lot of fast forwarding to the future, and I’m kind of wondering: What’s the plan for now?

- Another thing I’m intrigued by today? A new little phone called the Palm. The company bought the rights to the old one. It’s meant to be an accessory phone to your big everyday Android smartphone, so you have a little add-on gadget that does just simple stuff like texting and calls and music. It also fits in your pocket. Sounds kind of like the Apple Watch … except a phone … that goes with your other phone.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.