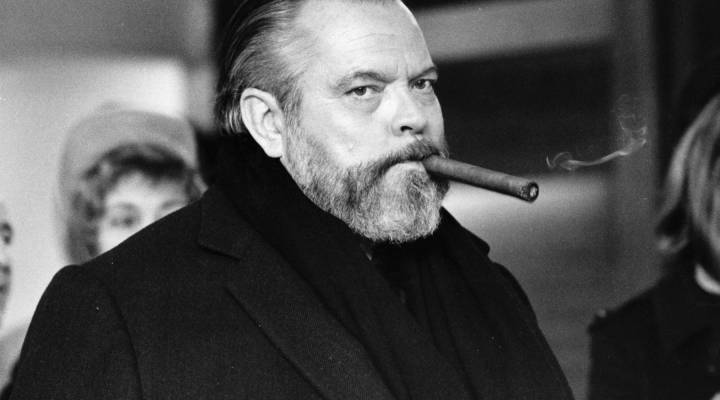

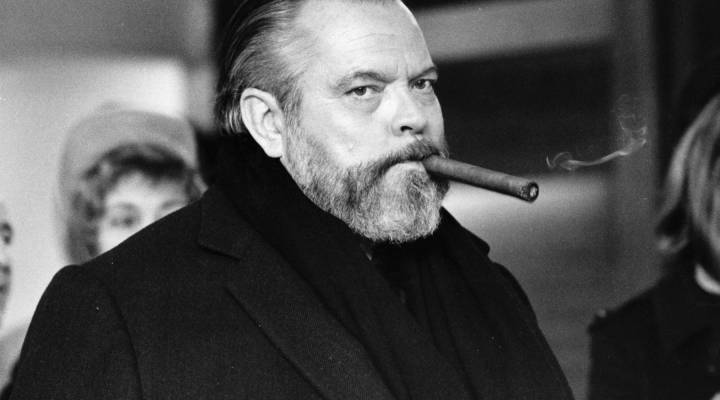

What Orson Welles and "War of the Worlds" taught us about economic panic

What Orson Welles and "War of the Worlds" taught us about economic panic

Eighty years ago Tuesday night, Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater went on the radio and panicked people coast to coast with these words:

“I can see peering out of that black hole two luminous disks … are they eyes? It might be a face. It might be … (shout of awe).”

It was just a radio play, a dramatization of the science-fiction story “War of the Worlds.” But many listeners freaked out, thinking it was either an actual Mars invasion or some other real disaster unfolding. Today, I’d like to think we’re more media savvy and could never be fooled by a radio play. But something about the original broadcast got us thinking. Here’s how Orson Welles set the stage:

“It was near the end of October. Business was better. The war scare was over. More men were back at work. Sales were picking up. On this particular evening, Oct. 30, the Crosley service estimated that 32 million people were listening in on radios.”

Consumer spending up, unemployment down. He’s almost doing a business report. What if you turned on the radio here in 2018 and they were not talking about civilization crushed by Martian invaders, but instead financial markets crushed by Wall Street technology, trading algorithms run amok?

What if instead of this:

“Professor Farrell of the Mount Jennings Observatory, Chicago, Illinois, reports observing several explosions of incandescent gas, occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars. The spectroscope indicates the gas to be hydrogen and moving towards the earth with enormous velocity.”

You heard this?

“Professor Farrell at the Financial Systemic Risk Bureau in Washington reports observing unusual trading volume pushing down bonds in five separate Asian markets overnight, causing a spreading liquidity crisis in European capitals.”

A radio drama of a financial crash, caused by technology we don’t fully understand, rolling across time zones headed for Wall Street. It’s fiction, but it’s somehow scary, right? It triggers a reflex to run for it. Especially given this is also the 10-year anniversary of the 2008 financial crisis. What we have here is a teachable moment about how we humans sometimes lose our minds in the face of the financial unknown.

Hersh Shefrin, behavioral economist and a professor of behavioral finance at Santa Clara University in Northern California, agreed during a discussion with Marketplace Morning Report’s David Brancaccio. Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Hersh Shefrin: So I think that it is an overreaction to particular situation simply because the need to survive has led us to having to react quickly when we perceive threats. So, panics effectively combine fight or flight reactions with crowd psychology and those panics are in some sense problematic but in some sense, but if we didn’t have them, the alternative could be worse if we sort of sat around when the threat loomed and didn’t react quickly enough.

David Brancaccio: And in a financial crisis you don’t gather your data firsthand unless you’re actually working in financial markets, you’re getting it from other sources and it could be ridiculous stuff you half-saw on social media or whispered rumors that the guy in the next cubicle just shared with you or, in the case of the Orson Welles alien invasion broadcast from 80 years ago last night, you thought that the radio was authoritative and it turned out that the radio was messing with you.

Shefrin: Yes, we’re really vulnerable once we get into these situations and so we have some fear enter … our minds are predisposed to look for evidence that supports whatever thought we have in our mind and so for a little bit fearful when something that’s potentially believable that supports that thought, that thought tends to get amplified, that emotion tends to get amplified. And if we’re in a social situation, then our feelings of fear get transmitted onto somebody else.

Brancaccio: So when the guy comes on the radio and says “sit tight with your portfolio, don’t do anything rash until you calm down,” it’s sometimes a little hard.

Shefrin: Oh, it’s tough. You know by that time the adrenaline has kicked in. But after a while, if our brain tells us, “you know what, this is short term, this is potentially long term.” That’s when cortisol kicks in and when cortisol kicks in, we’re dealing with a completely different ballgame and cortisol is what eventually degrades your ability to think rationally.

To that end, we leave you with a few more words from Orson Welles.

“So goodbye everybody, and remember the terrible lesson you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian … it’s Halloween.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.