With daycares still closed, child care providers and parents are grappling with who pays the bill

Share Now on:

With daycares still closed, child care providers and parents are grappling with who pays the bill

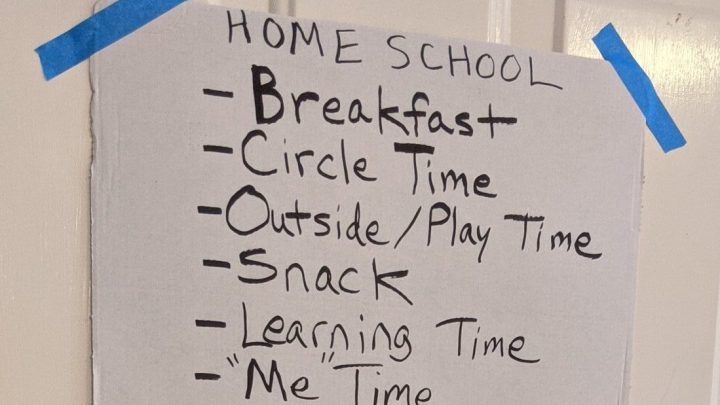

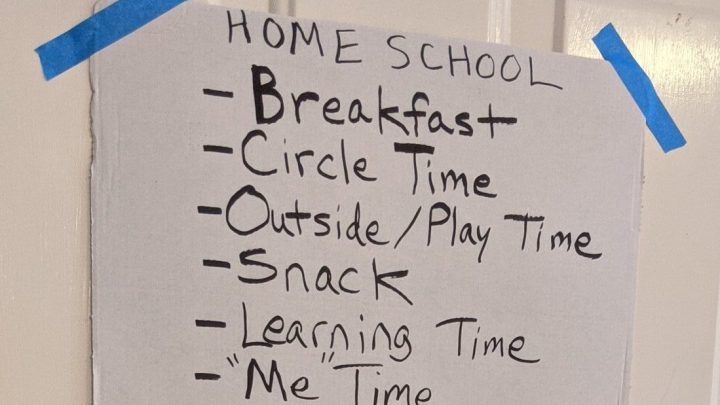

Back at the end of March, shortly after her daughter’s daycare closed for the foreseeable future, Allyson Criner Brown predicted that without clear guidance from city or state officials, it was soon “going to feel like the Wild West” as far as who was paying for child care and who wasn’t.

“These aren’t decisions that individual parents should have to make themselves, or that the daycare should have to figure out,” Criner Brown, who has a 2-year-old and a 6-year-old, said at the time.

Five weeks later, that is still what’s happening: parents and child care providers across the country are having to figure out for themselves, on a case-by-case basis, what to do about tuition while shelter-in-place orders remain in effect. Just about half of child care centers and nearly 60% of home daycares are still charging parents full tuition, and another 22% are offering reduced tuition, according to a survey out this month from the National Association for the Education of Young Children. More than 75% of families, though, have stopped paying.

That means, for the most part, there is “no income into child care programs, except for that little income that some parents, who can afford to, are willing to pay for services that they’re in fact not getting,” said Kim Kruckel, the executive director of the Child Care Law Center. “That’s basically what child care centers and programs are relying on.”

Many parents are acutely aware of that and feel varying degrees of responsibility to support the programs and teachers that care for their children. But with more than 30 million people newly out of work and 50% of American households having lost some or all of their income, it is getting increasingly difficult for many to justify paying hundreds or thousands of dollars a month for child care they’re not getting.

Criner Brown, who lives in D.C. and is worried about job security, pulled her daughter out of daycare soon after it closed in March.

“We just can’t take the risk that we make all of these payments and then we’re not able to get them back for not having our child go to daycare,” she said. “We’re not in a position to get months into this and then they say we need to do all these back payments if you want to come back to the daycare.”

Lauren Gard, a single mom in suburban Philadelphia, feels like continuing to pay her son’s daycare in full, even though it’s closed, and even though it’s a stretch, is the right thing to do. And she’s planning to — unless the daycare is able to get a loan from the federal Paycheck Protection Program or find another way to keep its teachers on staff.

“My key priority in thinking about paying is that I want to make sure the teachers and everybody else is paid,” said Gard, whose small public relations agency has lost about a third of its business in recent weeks. “My parents were both teachers, both of my siblings are teachers, it’s important that teachers get paid, and I’ll do whatever I can to make sure that happens on my end.”

Shane Slone is inclined to keep paying, too, if his sons’ daycare asks. At least for now.

“For us it’s a balance of trying to support the school — we want them to be there when all this is over — but also we have to make sure, with all the uncertainty, that we stay financially stable,” said Slone, who lives in Lexington, Kentucky with his wife and 2-year-old twin boys and runs a company that offers online continuing education for nurses.

“We’re paying for daycare that we’re not receiving, we’re paying for a gym membership, I have an office space that I can’t use,” Slone said. “There’s a lot of money going out of our household right now that we’re not getting anything in return for. And it’s just a little bit hard to swallow.”

It was one thing to keep paying for the first month or so that daycare was closed. That felt reasonable, especially after the school sent a note saying it was still paying teachers and rent, and asking parents to pay what they could afford — Slone and his wife decided to send in half tuition for April. But with the prospect of the school being closed for another month or two or three, he is starting to wonder where the line is.

“We’ve paid for six weeks of services now, and it’s hard to say, can you pay for six months of services? Or where do you draw the line on that? On something that you’re not able to utilize?” Slone said. “I want to think that people could support their schools and support their communities. But at the end of the day, I’m not sure that it’s 100% the parents’ role to support the business. There really should be government monies for these folks like there are a lot of other entities.”

Child care providers — 97% of whom are women, 40% women of color — are eligible for small business Economic Injury Disaster Loans, and for the new federal Paycheck Protection Program created under the CARES Act. But so far, it seems few have been able to secure that funding.

“A lot of talk has been made about the small business loans that became available through the CARES Act, and that was definitely a tremendous step in the right direction for many businesses,” Kruckel said. “But most child care centers and home-based child care programs do not have the business bank accounts, relationships with bankers, and professional support to navigate the Small Business Administration’s loan programs.”

Only about half of child care centers and just a quarter of home providers have applied for PPP loans so far, according to one survey. Nearly 70% are wary of taking on debt, worried they would end up having to pay it back.

Of the 300 or so providers Kruckel has heard from in California, only one has received a PPP loan. Ana Andrade, who runs her own home daycare and is president of the Marin Family Child Care Association, also knows just one person who has gotten a PPP loan, of the 40 she’s spoken to recently.

Andrade tried to apply herself, “but what I’m getting from my bank is, ‘we are trying, we are trying, we can’t get through.’ This PPP loan has been a fiasco,” she said. “Because all the big companies were allowed to apply for it, and no funds are available. It isn’t an easy thing, and I’m still waiting to hear from the bank to see if we can get through.”

Donna Mason wasn’t able to get through either, when she tried to apply for a PPP loan for the St. Albans Early Childhood Center in Washington, D.C., where she is executive director.

“It was just heartwrenching, to be honest,” she said. “We were so excited that the CARES Act was passed, and that this opportunity would be available. It was like a lifeline. And then to go through the process, in my particular case, being a part of a banking institution that had over 100,000 applicants with only 2,000 people processing these applications, it was just unbelievable.”

After being shut out in the first round, St. Albans applied again for the second round of PPP funding, this time through a smaller bank, and Mason is hopeful it will come through. In the meantime, the center is also seeking out other sources of funding and credit, from the SBA, the city, the bank, and has been asking parents to continue paying partial tuition, if they can — 75% for April, 50% for May. So far, most are.

But Mason recognizes that her school, in an affluent neighborhood in D.C., is in an unusual position.

“We’re in a community that has resources. That’s not the reality in the city,” she said. “I am concerned about the industry.”

Kruckel is, too. She and other child care advocates, she said, “are more concerned than ever that child care programs will not be able to reopen.”

Most programs are small, and operate on thin margins to begin with. Many providers, like Andrade, live paycheck-to-paycheck. Nearly a third of providers, both in-home and center-based, said in March that they would not survive a closure of more than two weeks without some kind of financial support. And while self-employed providers are now eligible for the expanded Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, many states, like California, are just starting to accept and process applications, six weeks into the crisis.

Andrade said she’s not counting on it. She’s heard what it’s like to apply for unemployment these days — busy signals, crashing websites, long waits for checks.

“We’re kind of learning not to rely on … any of those on the loans or unemployment or any of that because it’s just not happening, it’s not flowing,” she said. “It’s definitely not reliable.”

Instead, for now, she’s relying on the four families of essential workers who are still dropping their kids off every day. On the handful of families who are continuing to pay 70% of their normal tuition, even though she’s not able to care for their kids right now. And on the hope that eventually, maybe soon, she’ll be able to re-open again.

Though, she’s not sure what that will look like.

“I have no idea what’s going to happen when we open again,” Andrade said. “How many kids I’m going to be allowed to take. The families we’ve had on waiting lists, the children were supposed to start in summer or fall, what is going to happen? Nobody knows, not even the families themselves do.”

So for now, as she has since mid-March, she’s taking it day-by-day. And she’s improvising, trying to figure out what child care looks like in the age of social distancing.

Things like, “washing your hands, when to wear masks and gloves, and social distancing,” she said. “How do you practice social distance with a bunch of two year olds?”

Mostly, Andrade does it by having the kids spend a lot more time outside in her backyard, and very little indoors in the playroom.

For the time they do need to be indoors, she said, “I taped squares on the floor, and the children know that that’s their square. And they have a box with all their art supply and toys and stuff.”

It’s working with four kids. It’ll be harder, she knows, with more.

“Being a daycare provider right now goes against everything I’ve been about,” she said. “I cannot hug my children. We cannot hug, we cannot be together. And these children need to be hugged. They are little.”

They are also resilient, and they can get used to a lot, she’s found — like her wearing a mask — but the no hugging rule, that one’s tough.

“Last week we made masks because they were talking about my mask, so we made masks out of cloth, and they wanted to try them on. And the first reaction from one of the little girls said, ‘oh can I hug now?’ And she ran and hugged her friend because she was wearing a mask,” Andrade said. “That’s how they understand the world.”

Are you stuck at home with kids right now?

Check out our brand-new podcast “Million Bazillion.” We help dollars make more sense with lessons about money for the whole family.

Each week we answer a new question from a kid, like where money comes from, how to negotiate with parents, why things cost what they do and how to save up for something you want.

Listen here or subscribe wherever you get podcasts!

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.