In China, chasing debt after the COVID-19 lockdown

In China, chasing debt after the COVID-19 lockdown

Factory equipment supplier Wang Xiaojian came out of China’s economic shutdown from the COVID-19 virus relatively unscathed.

The 40-year-old runs a company in Shanghai that provides pumps and pipes to food and pharmaceutical factories. Wang has not laid off any workers and said business has been pretty much back to normal since March.

One thing that has changed is that he now chases his clients to pay their overdue bills weekly rather than every three months.

“About a third of my clients do not pay on time. This was happening even before the pandemic hit,” Wang said. “Some won’t transfer the money unless I remind them.”

According to a study released in early June by credit insurance firm Coface, 66% of companies in China surveyed said they experienced payment delays in 2019, which is up from 62% in 2018.

“We currently don’t have a survey for North America, but the figures [for payment delays] are higher in China than they are … in other European countries,” said Carlos Casanova, author of the Coface study and the firm’s Asia economist in Hong Kong.

“If a company doesn’t pay you in 180 days, 80% of the time they don’t pay you at all.”

Of the 1,000-plus firms surveyed by Coface, 27% of them reported that more than 10% of their annual turnover in 2019 was tied up in payment delays of more than six months, which could create cash flow risks.

Chinese people care a lot about relationships. If I chase my clients too aggressively [to pay their overdue bills], it might hurt their self-esteem.

Shanghai businessman Wang Xiaojian

Fabric trader Zhang Baoguo, 37, in eastern Zhejiang province, was in the same situation heading into the pandemic.

“In 2014, payments would arrive one month after we delivered. That became 45 days, then three months. Now payments take six months or more,” Zhang said.

He keeps working with these clients because the business environment has not been as good in the downturn of the past few years. There is too much competition and less easy credit.

“Big brands won’t give us a down payment. There is overcapacity in the textile industry, and if I don’t accept their payment terms, other firms will. Then that will put small players like me out of business,” Zhang said.

Plus, leading up to the pandemic, all his clients paid eventually.

“My clients only need to pay back a portion of the overdue payments at a time, because as a fabric trader, I can also buy from my suppliers on credit. This is the pattern in the industry,” Zhang said.

That pattern has become riskier as China’s economic growth has slowed in recent years and the United States and China are locked in a trade war. Add the impact of the pandemic, and 2020 is working out to be a very challenging year for Chinese companies.

“Growth [is] expected to drop to 1% in 2020. That is quite unprecedented,” Asia economist Casanova said.

“Pockets of stress continue to be present in the Chinese economy, calling for even more insolvencies in 2020,” he wrote in the June report.

The COVID-19 crisis has wiped out overseas orders from Japan, South Korea and the U.S. for fabric trader Zhang. He has laid off one employee and downsized his office space.

Zhang said he has some domestic orders that should keep him afloat, though he admits, ruefully, that these days he has a lot more free time to go fishing.

Like many Chinese people, he has savings and has already paid off his home mortgage and car loan.

As for factory equipment supplier Wang, he is more proactive about chasing late payment during the pandemic.

“I told my staff that if they can’t collect overdue payments, I will deduct the money from their year-end bonus,” Wang said.

It is a way to put pressure on his staff to take payment delays seriously.

![A plea from light seller Zhang Peng on his WeChat social media feed reads: "Dear god, please pay off the debt you owe me whether the sum is big or small. My lunch consists of rice with a bit of Lao Gan Ma chili sauce. If I don't receive payments soon, I won't be able to afford white rice either!"]()

Light seller Zhang Peng wrote on his WeChat social media feed: “Dear gods [customers are sometimes called gods in China], please pay off the debt you owe me no matter if the sum is big or small. These days I eat rice with a bit of Lao Gan Ma chili sauce for lunch. If I don’t get paid soon, I might not even be able to afford the rice!” ![A plea on social media app WeChat: "Dear bosses, there's only two days left before the Lunar New Year. Please pay the overdue invoices. I also agreed to pay off my debts so, please don't put me in a tough spot. We still have to see each other during the holidays!"]()

Another entrepreneur wrote: “Dear bosses, there are only two days left before the Lunar New Year. Please pay your overdue invoices. I also agreed to pay off my debts so, please don’t put me in a tough spot. We still have to visit each other during the holidays!”

In the 16 years since he’s been in business, Wang said he has only had one client default on payment.

Wang took the firm to court and won. The company has since declared bankruptcy, and Wang still has not seen any money he is owed.

For Wang, doing business in China is all about what the Chinese refer to as ‘guanxi’ or personal trust and connections.

“We operate on mutual trust. Contracts are useless. The courts can’t do much for us either,” Wang said.

![]()

Fabric trader Zhang Baoguo has more time to fish with business plummeting during the coronavirus. ![]()

(Courtesy of Zhang Baoguo)

However, Wang said he cannot push clients too hard to pay their overdue bills.

“Chinese people care a lot about relationships. If I chase my clients too aggressively, it might hurt their self-esteem,” he said.

For him, it is best to have an excuse when chasing debt. A great time to do it in China is the end of the lunar year because businesses need to close their books.

This practice is so widespread that it is common to hear people chasing debt or being asked to pay up on public transport.

“You need to send me an invoice for 93 days. How much money is it per day? What is the total?” a man at the Shanghai Hongqiao railway station shouted into his phone back in January, ahead of the Lunar New Year and just days before the pandemic shut down much of China’s economy.

“You only sent me a picture of your bank card. How do I know how much money I owe you?”

His partner stood next to him punching numbers into a calculator.

“A contractor wants us to pay him, but we also need others to pay us,” he said without giving their names for fear that their clients would get mad and not pay up.

The two men said they have more than a million yuan ($140,000) in unpaid invoices and are chasing their clients by phone.

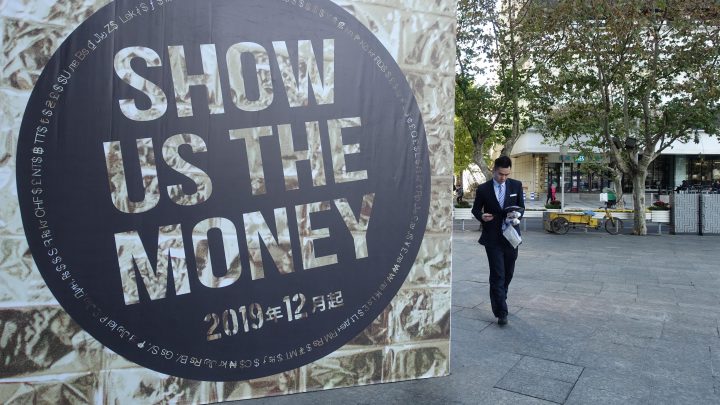

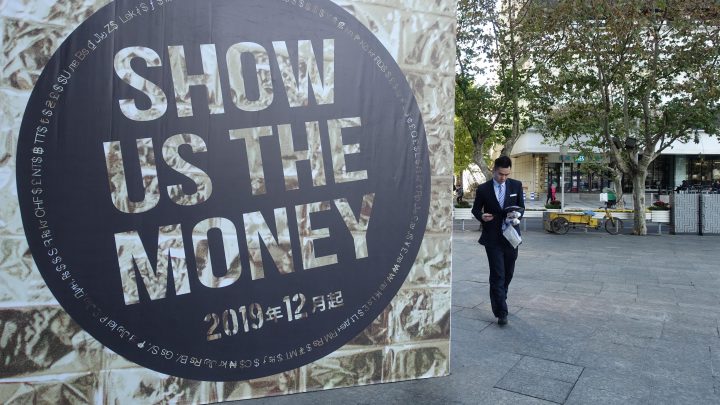

![]()

Professional debt collectors advertise across Shanghai. ![]()

![]()

(Charles Zhang/Marketplace)

Humor can help the process, too.

Businessman Zhang Peng sells lights. He posted a video on the Douyin app, which is the Chinese version of TikTok.

“Dear clients who owe me money, please send your payment to me,” Zhang said in the video and pointed the camera to a bowl of rice topped with a household-brand chili sauce by Lao Gan Ma.

“Take a look at this: Without money, I can only afford to have Lao Gan Ma chili sauce on my rice. I have no money to buy pork and vegetables. Please send your payment to me as soon as possible!”

Additional research by Charles Zhang.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.