How the election certification process works, and why it matters

Election certification happens after every general election. This year, it’s looking to be costly.

It’s been nearly a week since the Associated Press officially called the 2020 presidential race for former Vice President Joe Biden. But the election won’t be certified for weeks to come.

While President Donald Trump’s refusal to concede is unprecedented, the certification process is not. It happens after every general election to ensure the accuracy of the vote count. But certification is getting a lot of attention this election, with the Trump campaign filing lawsuits in key states in an attempt to slow the process. So what is election certification, when does it end and will the lawsuits have any effect on the outcome?

What is election certification?

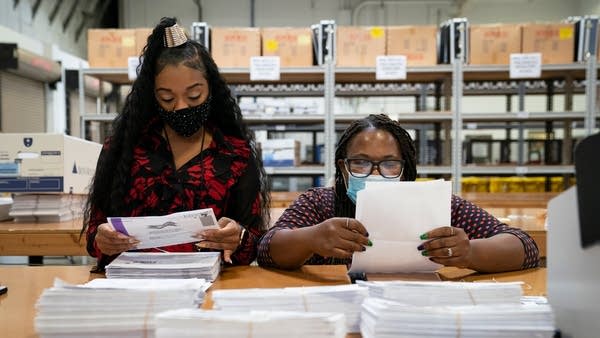

The results we see on TV on election night — or in this year’s case, the Saturday after — are not official. They’re projections made by news outlets based on modeling. Official election results don’t come until days or weeks after Election Day. A process called canvassing takes place in every state by which officials ensure that every valid vote is counted. This includes absentee ballots, early voting, Election Day votes, votes from overseas and challenged votes. It also allows time for any recounts to happen.

“It culminates in having designated state officials provide a formal stamp of approval for the election,” said Robert Yablon, associate professor of law at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and expert on election law. Depending on the state, that official could be the secretary of state, an elections commission or a board of canvassers created for this purpose.

The state governor then prepares a Certificate of Ascertainment, which is sent to archives at a federal level.

The process is the same this year as it is any other. Yablon said logistics might be a little different for states due to the record amount of votes cast before Election Day, but the process remains the same.

When do states finish certifying an election?

It depends on the state and its laws, but every state has to certify its election by the “Safe Harbor” deadline, which falls six days before the Electoral College votes. That deadline is Dec. 8 this year. Here are the dates in key states:

Georgia: The secretary of state has until 17 days after the election to certify results, Nov. 20 this year.

Pennsylvania: Nov. 23 is the last day for county election boards to file their results to the state.

Michigan: The Board of State Canvassers meets Nov. 23 to canvass the general election.

Arizona: The secretary of state canvasses on the fourth Monday after Election Day, Nov. 30 this year.

Wisconsin: The Chair of the Wisconsin Elections Commission has until Dec. 1 to certify statewide results.

How much does election certification cost?

Much of the cost of election certification comes from reviewing challenged votes and recounts. A general price tag for certification is hard to come by, but Yablon offers one example of the 2016 statewide recount in Wisconsin.

“It ended up being a little bit more than $2 million, and most of that is labor related costs,” he said. “Now you are going to have thousands of workers that have to come in to do this work.”

One recount that is looking to be particularly expensive is Georgia. The secretary of state has ordered a hand recount of the nearly 5 million ballots cast, an incredibly labor intensive process.

Who ends up paying for the recounts depends on a couple factors. In some states, a thin margin automatically triggers a recount. In other states, a campaign can request a recount, but then has to foot the bill. Even then, in some states, if a campaign requested the recount and there is a significant change in the outcome, the campaign is refunded and the state pays for it.

“In the states where the state absorbs the cost, actually a lot of that is down to the local level,” Yablon said.

“This can be a real budget hit to local governments,” he said, especially considering local governments are already slammed due to COVID-19.

What’s the effect of the Trump campaign lawsuits?

Trump’s campaign has filed lawsuits in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Arizona, calling for judges to stop states from certifying election results with claims of election fraud and limits placed on poll watchers. (To be clear, there is no evidence of widespread election fraud. A joint statement released Thursday from federal agencies states the Nov. 3 election “was the most secure in American history.”) If states don’t certify their election results by the deadline, it then falls to the state — usually the executive of that state — to choose electors. The thinking is that those states would choose electors sympathetic to Trump, said Casey Burgat, director of the Legislative Affairs program at the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University.

“It’s a really “House of Cards”-y maneuver in that it’s purposeful in overturning the will of the people,” he said of the strategy. “It’s about seven chess moves of garbage.”

But the likelihood of lawsuits working as intended is slim to none.

“I can’t imagine that across each of those three states, it would be done to that magnitude,” Burgat said. “You’d have to get all of them to make it worthwhile, and that [would be] a lot of votes and a lot of ballots just basically being thrown out.”