Two-thirds of people in advanced economies are poorer than their parents

Two-thirds of people in advanced economies are poorer than their parents

This interview is from our series Econ Extra Credit with David Brancaccio: Documentary Studies, a conversation about the economics lessons we can learn from documentary films. We’re watching and discussing a new documentary each month. To watch along with us, sign up for our newsletter.

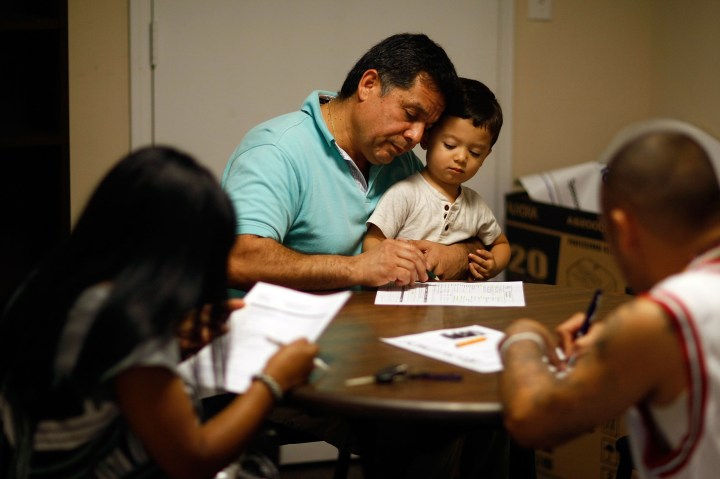

In advanced economies like the U.S., the 20th century was marked by steady income growth for the middle class. A 2016 report by the McKinsey Global Institute found that between 1993 and 2005, 98% of households in advanced economies saw their real incomes rise.

But the following decade, 65% to 70% of households in those same economies saw their incomes stagnate or fall. In the U.S., it’s more like 80%.

“Of course, we have to remember that that period, 2005-2015, included the 2008 recession. But the rest of it [was] the result of long-term trends that have continued even to this day,” said James Manyika, chairman and director of the McKinsey Global Institute, who co-led the 2016 report.

And since then, inequality has continued to accelerate — which Manyika said requires us to reimagine capitalism in countries like the U.S.

“We have to think about, how do we tackle these vastly unequal outcomes that we have in the way our economy works?” Manyika said in an interview with “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: No. 1 — what? Really? And No. 2, what’s causing this?

James Manyika: It was a staggering statistic for us, David. So this is from our 2016 study, which we called “Poorer than their parents?” And we had looked across all the advanced economies to see what had happened to incomes and economic well-beings for people. And we found that two-thirds of people living in the advanced economies had seen their incomes stagnate in the decade between 2005 and 2015. The reason this is such a staggering number is because if you had compared that to the decade before that, only 2% had seen their incomes stagnate. So in other words, in the decade before 2005 and 2015, 98% of people living in advanced economies would have seen progression, their incomes were increasing year after year after year. So the two-thirds stagnation is staggering.

How we work is changing

Brancaccio: What are some of the broad forces that lead to this?

Manyika: Well, I think there are several things at play here. Of course, we have to remember that that period, 2005 to 2015, included the 2008 recession. But the rest of it were the result of long-term trends that have continued even to this day. So we know that, for example, we’ve had the impact of globalization. We know that, for example, technology has started to change the workplace. We know that, for example, productivity, which has been the longstanding engine for economic growth, doesn’t lift up wages as much as it used to.

Brancaccio: And our relationship with work is just different than it used to be. I mean, you don’t know how long you’re going to hold a job. Often people are cobbling together many jobs in many of these countries.

Manyika: Yeah, and I think it’s been changing in several important ways. You just mentioned one. So one of the things that’s interesting in the 21st century is that while of course we have grown the number of jobs, a lot of the growth in jobs has been of the alternative variety. Something like two-thirds of the net additional jobs are alternative. By alternative, I mean they’re either part-time, contingent, independent work, so called “gig work,” etc. And that brings in a certain degree of work fragility. So incomes become a little fragile, you don’t know if what you earn this year is going to be what you’re going to earn next year or next month. The certainty of employment itself becomes a little bit more fragile. And also the traditional career pathways that allow people to progress from potentially being a janitor all the way to one day maybe even being the CEO, those pathways don’t exist as much as they used to before. So work is changing.

How the COVID-19 pandemic affects these trends

Brancaccio: The original report that you did is 2016. You say the trends continue, but with [the] pandemic, dare I even ask, it must be making things worse.

Manyika: So when COVID hit, it exposed these challenges even more. So while everybody is counting the number of unemployed workers, we should really look at a much larger number, which we call vulnerable workers. These are workers who have either been furloughed, laid off, have had their work hours or incomes and wages reduced. And if you look at it that way, it’s actually about a third of U.S. workers who are vulnerable in that way. And that’s a much larger number than just the unemployed. The majority of them, 80% of them, are low-income workers. These are workers who earn less than $40,000 a year, and a lot of those workers, again, are disproportionately women and people of color.

Focusing on education, distribution of job growth and inequality going forward

Brancaccio: So I know we could convene a symposium about the following question, but where might we focus our attention to reimagining an economy where the future for the next generation is not worse?

Manyika: I think one of those is to really think about the role that education plays. One of the things that has declined dramatically over the last 20 years especially is the amount of investment we make in public goods. Public goods is education, infrastructure and so forth, that allows people to be able to participate in the economy. I think we have to focus there.

I think we also have to focus [on] this question of geography of work. It’s striking that we’ve been celebrating job growth that has happened from the Obama years to the Trump years where we’ve created nearly 9 million jobs. Two-thirds of that job growth has been concentrated in 25 cities and dynamic hubs in America, while the rest of them have seen either flat job growth or even declining job growth. So the second place we have to focus on is this question of, how do we make sure that all parts of the country are seeing sufficient investment, there’s enough business activity that actually enables everybody across the whole country to fully participate? We can’t afford to have the kind of geographic concentration of economic vitality that we have right now.

The final one is to reimagine how we make sure that, as our economy does well, we don’t have the staggering inequality that we have. It’s quite striking, if you look at the United States, that over the last 20 years, if you were in the top two quintiles of workers — that’s roughly about 100 million people — this was wonderful. Innovators did well, entrepreneurs did well, investors did well. If you had high skill, high wages, you did well, But for the bottom three quintiles, and that’s about 150 million working-age Americans, this was mostly miserable, because the income inequality was quite staggering. The cost of living for these Americans became unbearable because the cost of housing, education and health care, in particular, went through the roof. So we have to think about how do we tackle these vastly unequal outcomes that we have in the way our economy works.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.