You can now own “authenticated” digital artwork. Is that a good thing?

You can now own “authenticated” digital artwork. Is that a good thing?

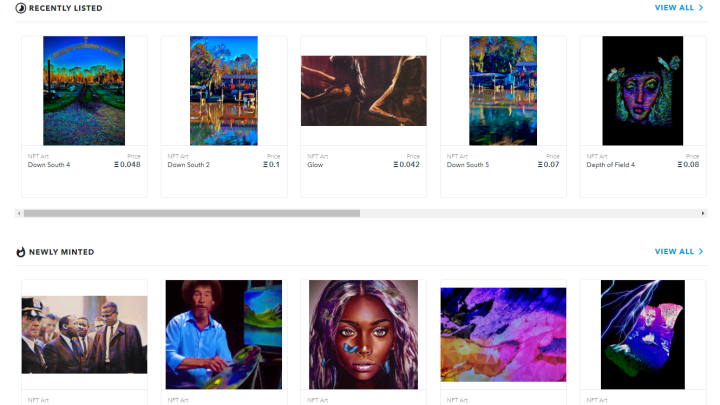

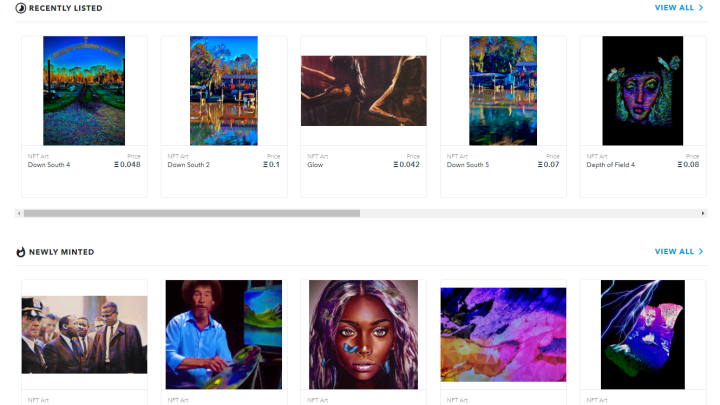

A 10-second video created by digital artist Beeple recently sold for $6.6 million in an art auction. But what made this one video different from any number of copies or “forgeries” on the internet that are otherwise indistinguishable from the original?

The video itself is a “non-fungible token” or NFT, a digital asset whose origin or ownership has been authenticated by blockchain technology, much like a digital “signature.” One NFT cannot be exchanged for another NFT, which makes each one uniquely valued.

While this is making it easier to assign monetary values to digital art, critics like Blake Gopnik are afraid this will replicate a problem that’s been affecting the physical art sector for generations: valuing art for its authenticity but not for the art itself.

“Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio spoke to Gopnik about the issues with authenticity in the digital art space. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: Non-fungible tokens with digital artwork. Blockchain says it is the original. Sounds very “au courant,” but no?

Blake Gopnik: No, it’s the way people have been thinking about art for about 500 years. We’ve all been completely obsessed with who makes a work of art and proving that it’s the real thing. You know, you want your Leonardo [da Vinci] to be by Leonardo, not to be by a follower, even if you love how it looks, when it’s by a follower. People who buy NFTs, or NFT-based art, just want to know that they’ve got the real version of the rainbow cat video that a million other people just have copies of. But, of course, they’re not copies, they’re exactly the same thing. So people are spending all this money just on these certificates, on these non-fungible tokens, that tell people that you’ve got the real thing. But the real thing isn’t real in any real way.

The art world and authenticity

Brancaccio: I mean, one of the things here through my non-critic eyes is if you go see the “Mona Lisa” in the Louvre in Paris, you can see brushstrokes, so the original is different from seeing the copy in the art book. In the case of this authenticated video, there is no difference looking at the original or a copy.

Gopnik: Yeah, it’s completely insane. But, again, that’s been happening for a long time in the art world, too. I mean, people produce prints, some of which they sign, and those are worth a fortune, and some of which they don’t sign, and those are worth much, much less or nothing at all. So the art world has always been weird about this. It’s always been trying to establish authenticity for objects that really aren’t that different from other objects. But this is just taking it to a new level where your video is absolutely the same as someone else’s.

Now normally in the art world, what you do is when you’ve got, say, a work of video art that you’ve got in a DVD, is you make sure that you don’t release it in a million copies. You just make five copies, and five collectors can own them, you know, for whatever, $100,000 each. But in this case, people are buying these things because they’re already famous, because they already exist in thousands and thousands or millions of copies. So it’s a really weird reversal. If you’re buying the Nyan Cat, this cat that’s dragging a rainbow after it, you’re only buying it because it’s so famous already, because so many other people actually own it. So it’s a very weird, really absurd, kind of ownership.

Brancaccio: And here we are talking about the system of authenticating the work, but not the work itself. This 10-second video by Beeple.

Gopnik: Yeah, video of a kind of putrescent corpse of Donald Trump lying on the ground. You know, no one in my world, no one in let’s call it the “serious art world,” would look at those things for a minute. And I don’t think that people buying these works are saying, “Wow, these are really major works of art that I want to stare at, you know, again and again, and try to figure out why they’re so magical.” They’re buying them really just because of the hype already attached to them. No one, I hope, no one is saying these are timeless works of human creation and ingenuity, because they’re just completely trivial as artworks.

“People are spending all this money just on these certificates, on these non-fungible tokens, that tell people that you’ve got the real thing. But the real thing isn’t real in any real way.”

Blake Gopnik, art critic

Brancaccio: That’s kind of too bad in your view, right? That we’re always worrying about ways to limit the supply of something, to boost value, and not having enough conversation about, is it good or not?

Gopnik: Yeah, it’s amazing how much people like to talk about whether something is really by someone or not. I mean, the case of forgery is kind of obvious, right? You have this work of art that everyone says is an amazing, fabulous work of art, and then one person comes along and says or proves it’s a forgery, and all of a sudden you don’t look at it anymore. You don’t care about it. Or, when a work by Rembrandt, like “The Polish Rider,” when a famous scholar comes along and says, “Oh, you know what? That picture we’ve all been liking so much? Turns out, it’s not by Rembrandt.” Then we’ll say, “Oh, what a shame! That used to be a good picture.” You know, it’s a crazy situation, and it’s always been there in the art world. But the NFT art is really, has gone crazy for it. But you know, I kind of like the idea that maybe they’re closet conceptual artists. Maybe they’re making us all think about the absurdity of authentication, when we wouldn’t normally think about it.

Brancaccio: And very effectively so. Now, you’ve spent recent years completely submerged in the world of Andy Warhol. You think he interacted with some of these ideas during his time?

Gopnik: You know, Warhol was obsessed with the issue of authenticity and its absurdity. So he placed ads in the Village Voice, saying that he would sign any object that you brought to his studio and turn it into a Warhol just by having signed it, by attaching a token to it, by attaching basically an NFT to any object that you chose. And, he would make silkscreen posters, some of which he would sign and some of which he wouldn’t sign, just to play with these concepts of authenticity to really underline how crazy they were. Now, that was 60 years ago this year that he started doing this. And it’s weird that people still don’t realize that there’s an issue there, that it’s kind of crazy to care so much about having the original, the authentic, the signed, the tokenized work of art.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.