Earmarks make a comeback in a closely divided Congress

House Democrats are leading efforts to bring back so-called earmarks in hopes it may help them move legislation in the narrowly divided Congress.

While some legislation, like the latest COVID-19 relief bill, can be pushed through using the congressional maneuver of budget reconciliation, other major bills, such as the infrastructure legislation introduced this week, are likely to require more bipartisan buy-in.

Congress banned the practice of allocating federal discretionary funds to specific projects based on member requests after 2010. Now the House Committee on Appropriations is aiming to bring them back as community project funding, with new limits on the types of groups eligible to receive such funds and greater transparency on who gets the money and why.

Earmarks became something of a dirty word at the height of their use, thanks in part to loud complaints from small government groups like Taxpayers for Common Sense, which tracks the thousands of line items in congressional appropriations bills.

“If you go back to the early 1990s, you had about 3,000 earmarks in the spending bills that fund government,” said Steve Ellis, the group’s president. “By 2005, there were more than 15,000 earmarks that were funding government.”

Ellis’ group identified and nicknamed the infamous “Bridge to Nowhere,” a regular target in the stump speech of 2008 vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, who originally supported the infrastructure project.

Ellis said the old system left a lot of openings for abuse, and he is concerned that bringing earmarks back, even with greater oversight, will still lead to government waste.

“Anytime you’ve got money that’s able to be thrown around, you’re going to have lobbyists that are going to try to get that cash on behalf of their clients,” Ellis said.

But earmarks were also very popular with many voters, since they often supported local projects that might not otherwise get a piece of federal funding.

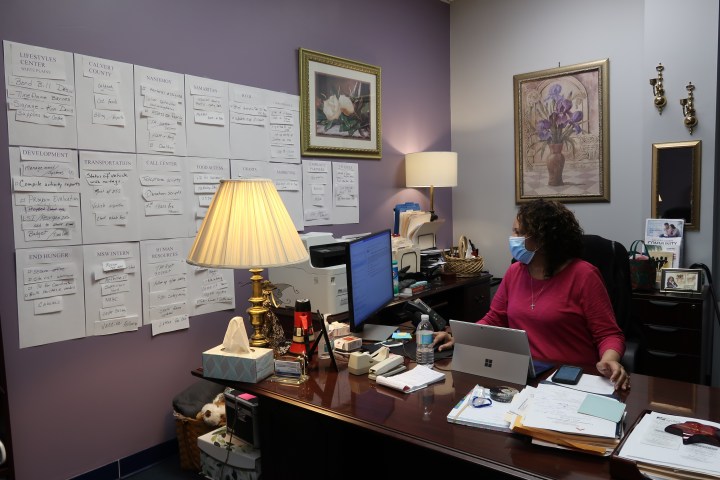

Sandy Washington runs the nonprofit social service provider LifeStyles in La Plata, Maryland. The group received a $60,000 earmark in 2010, just before the ban.

“And we actually set up our Homeless Services Center, where we put in showers, laundromat or laundry room, all of that,” Washington said. “So people can come and take their showers and do that type of thing. That [money] was tremendous.”

Another reason why proponents want to bring back earmarks is because they say they’ll make Congress more productive by giving members more incentive to compromise.

“I think this is, of all the different congressional reforms that you could pass, the lowest-hanging fruit that has the greatest capacity for positive change,” said Laura Blessing at Georgetown’s Government Affairs Institute. “Particularly for [members of Congress] who are expecting a close reelection fight and want to credit claim that they got something important for their district.”

Blessing found in her research that since the earmark ban, getting spending bills through Congress, which was tough even in the best of times, became basically impossible.

And for small nonprofits like LifeStyles in Maryland, which received a total of about $660,000 in earmarks in the years leading up to the ban, according to Sandy Washington, the ban was devastating for their funding.

“You feel kind of, you’re lost in a crowd,” Washington said of competing nationally for federal grants and funding. “We’re serving anywhere from [13,000] to 15,000 people a year. So when I look at that, and I look at the services that we’re providing, I have to yell the loudest.”

Proposed rules for the return of earmarks include stricter limits and more transparency. In the meantime, Washington already has a plan for her first request if earmarks do come back. She said she’ll ask her representative for $700,000 to finish converting an old hotel to a new homeless shelter.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.