How to achieve vaccination equity? In Philly, the answer is walk-in clinics

How to achieve vaccination equity? In Philly, the answer is walk-in clinics

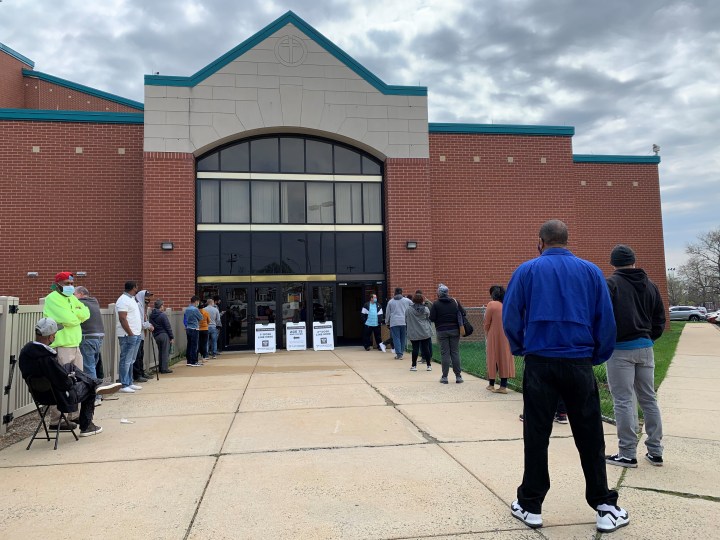

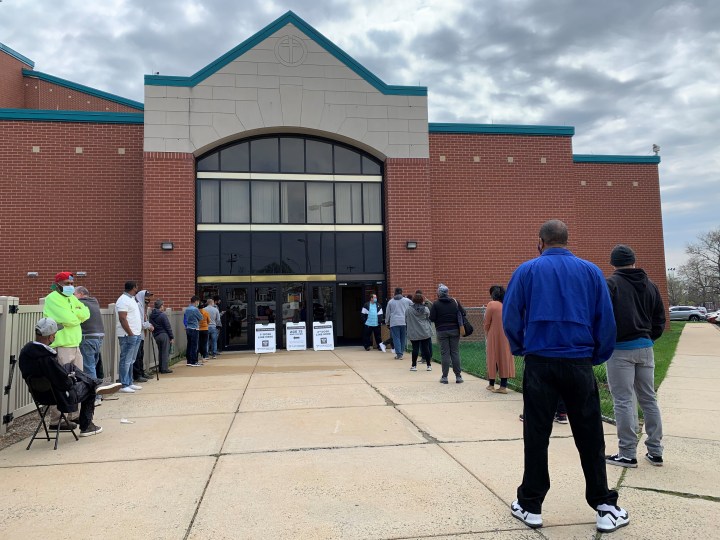

These days, there’s pretty much always a line in the parking lot outside Deliverance Evangelistic Church in Philadelphia. Five days a week, anybody who lives in any one of the city’s hardest hit zip codes can walk up and get a COVID-19 vaccine there — no appointment necessary.

Last Wednesday, Martin Valle was one of the people standing in that line. He came to church for afternoon service, looked over and spotted it. Out of curiosity, I said, ‘Let me try,’” said Valle, 49, who owns a janitorial company in the city. “Cut out of prayer service to come stand in line.”

Until he came down with COVID and was sick for three weeks, Valle hadn’t been sure he wanted to get the vaccine. “It was horrible, I lost 26 pounds,” he said. “So that’s the incentive. I don’t want it again.”

Other than his wife, who’s a nurse, Valle doesn’t know anyone who’s been vaccinated yet. Until the moment he saw the line, he didn’t know when or how he was going to get it, either. He said he found online sign-ups too complicated.

The church clinic, run by the nonprofit Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium was the first place Valle had seen where he could just walk up and get a shot. “I’m computer illiterate,” he said, “this is just simple.”

More than 123 million people, almost half of the adults in the U.S., have now gotten at least one dose of COVID vaccine and, on average, around three million doses are being administered every day.

Four months into the vaccination campaign, however, there are still significant disparities by race and ethnicity. In nearly every state that’s reporting data, white residents are being vaccinated at higher rates than Black and Hispanic residents, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation — more than 1.5 times higher, on average, in the 43 states Kaiser analyzed.

In Philadelphia, there is evidence that walk-in clinics can help reduce those disparities. For the most part, as in much of the country, if you want a vaccine you have to find an appointment and sign up online. That’s how the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium was operating at first.

“We started like everybody else, with this online registration system,” said Dr. Ala Stanford, a pediatric surgeon and founder of the Consortium. “Initially, greater than 90% of the people that were signing up were African American.”

Within a week, though, that number dropped to about 50%. “Then you could just look out the window and you could see Teslas and Mercedes and Range Rovers,” Stanford said. “In the area where I am, where the same people would never be caught in these neighborhoods, now they’re here.”

After just two weeks, she decided to scrap online registration and implement a walk-in model. “We made it first-come-first-serve. So if you were poor, you stood in line, if you were rich, you stood in line,” Stanford said. And you had to live in one of a group of the city’s hardest-hit zip codes.

“What we were doing was trying to level a playing field that has not been level for African Americans in the city, especially, since I was born and raised here,” said Stanford.

It’s working. More than 70% of the people the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium is vaccinating now are Black. Stanford attributes a lot of that to the clinic operating entirely on a walk-in basis.

A recent experiment the city did backs that up. Last month, Philadelphia reserved half of the doses at one of its FEMA-run vaccination sites for walk-ups, for six days.

“Walk-ups was kind of an eye opener,” said James Garrow, a spokesperson for the city’s Department of Public Health. “It was the first chance that we had had to do walk-ups at one of our clinics, and [we] saw a marked improvement in the racial demographics of the folks who had vaccine administered.”

In those six days, the number of Black and Hispanic residents getting vaccinated increased by more than 50%. Of all the ways the city has tried to improve racial equity in vaccine access so far, Garrow said, none have been so effective.

Now, the city is starting to do walk-ups again at another of its vaccination clinics. Dr. Stanford welcome the development, but wonders why it has taken so long. “We know what works for Black and brown communities,” she said. “It’s just frustrating, beating your head against the wall just to get what I feel like is basic equity.”

When the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium first started administering vaccines, it was doing about 1,000 a week; now it’s doing between 1,000 or 2,000 a day.

Barry Hopson got his first Moderna shot at the clinic about a month ago, in mid-March. For that one, he said, waited in line for about five hours.

“But that’s alright,” said Hopson, who’s 60 and retired. “I was very privileged to be able to be here. I’ve had a family member pass away from COVID-19. I said, ‘I’d rather wait in line to get the shot than wait in line for an undertaker that has to put me in the ground.’”

When Hopson came back last Wednesday, for his second shot, the wait was much shorter.

“Like anything that you do every day, you just get more efficient, right?” Stanford said. “Now, on average, we vaccinate about 150 to 200 [people] an hour.” Sometimes even close to 300 people an hour, if there’s enough staff. Which means the lines now tend to move fairly quickly.

For Martin Valle, it took about 45 minutes from the time he first saw the line in the church parking lot to the time he got the vaccine.

“It’s funny, now I’m going to be an advocate of it,” Valle said with a laugh, just after his vaccination. “I’m gonna let everybody know, go get your shot! Tell ’em to come right on down here and get your shot.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.