Pandemic innovation: High-tech family doc brings back the house call

Pandemic innovation: High-tech family doc brings back the house call

Work from home. Shop from home. See the doctor from home, permanently?

One Southern California family physician is betting on the old-school house call (and virtual visit) model, ditching his office space in favor of health care on the go.

And yes — he carries a black bag.

“Medical equipment, wipes, injection, stethoscope,” said Michael Kurisu, a family doctor in the San Diego area, during a home visit to a patient last week. Those were some of the contents of his bag. But he was also armed with high-tech diagnostic tools: wearable smart watches and rings for his patients to continually collect biometric data.

“Here’s a few Oura Rings that I’m going to be giving to a few patients later,” said Kurisu, whose solo operation is called Measured Wellness. “This is a wearable device that’s mainly used for sleep. But it’s also tracking your heart rate, your heart rate variability and your respiratory rate, and your core body temperature.”

So by the time he walks into the home of a patient, in this case Dennis O’Connor, Kurisu has plenty of vital-sign info. “I know what his sleep has been over the last week. I know what his heart rate has been.”

Kurisu and O’Connor go over what they call medical dashboards — charts of O’Connor’s blood pressure, weight and physical activity, among other biometric indicators — before the examination.

“So I did some dancing in the shower this morning,” O’Connor said, “a little bit of walking, and [it] measures my fitness level.”

Seeing patients at home, whether in person or on a screen, gives family doctors clues to their eating habits, cleanliness, medicine routines and risk of falling. Integrating tracking data from the wearable devices, Kurisu adds a layer of technology to the country doctor model, keeping regular tabs on all his patients and making them happier than they were under the old, office-based system.

“Health care, like the rest of the economy, is moving to being consumer directed,” said Dr. Randolph Gordon, a primary care and public health physician as well as a consultant at Deloitte. “It’s a matter of convenience. It’s a matter of expectation. And we are at a point with the pandemic that technology enables us to do that.”

“Health care, like the rest of the economy, is moving to being consumer directed. It’s a matter of expectation.”

Dr. Randolph Gordon, Deloitte

Gordon said the broad use of telemedicine during the pandemic lockdown represented a five-year jump on an already accelerating trend.

“So it’s a forced experiment, if you will, to give us a chance to evaluate those outcomes. And that’s a great thing,” he said. “It just makes sense because it’s what the consumers desire and what health care leaders think the future should be.”

To be clear, Kurisu’s new business model has yet to be proven, but he’s all in on the venture. He ended his office lease during the pandemic, saving $7,000 a month in rent and overhead. He’s now entirely on his own, practicing what he calls “high-tech, high-touch” medicine.

“I don’t need nurses. … I need a data scientist … to go dispatch me.”

Michael Kurisu, family doctor, Measured Wellness

“The doctor of the future is datacentric,” he said. “I don’t need nurses or [medical assistants] anymore. I need a data scientist who is looking at the data, who is looking at the trends going on, seeing where the red flags are, to go dispatch me. ‘Hey, you need to go make an intervention on this patient.’”

Like many innovations, Kurisu’s came out of necessity. For years he worked at a University of California, San Diego, clinic and a private practice. Both shut down last spring.

“There was no revenue stream coming in for me, so that pressure-cooker situation allowed me to be really creative.”

Kurisu began to see patients online and at their homes — which he’d never done. Most of his patients are on Medicare, which during the pandemic emergency is paying doctors for these services.

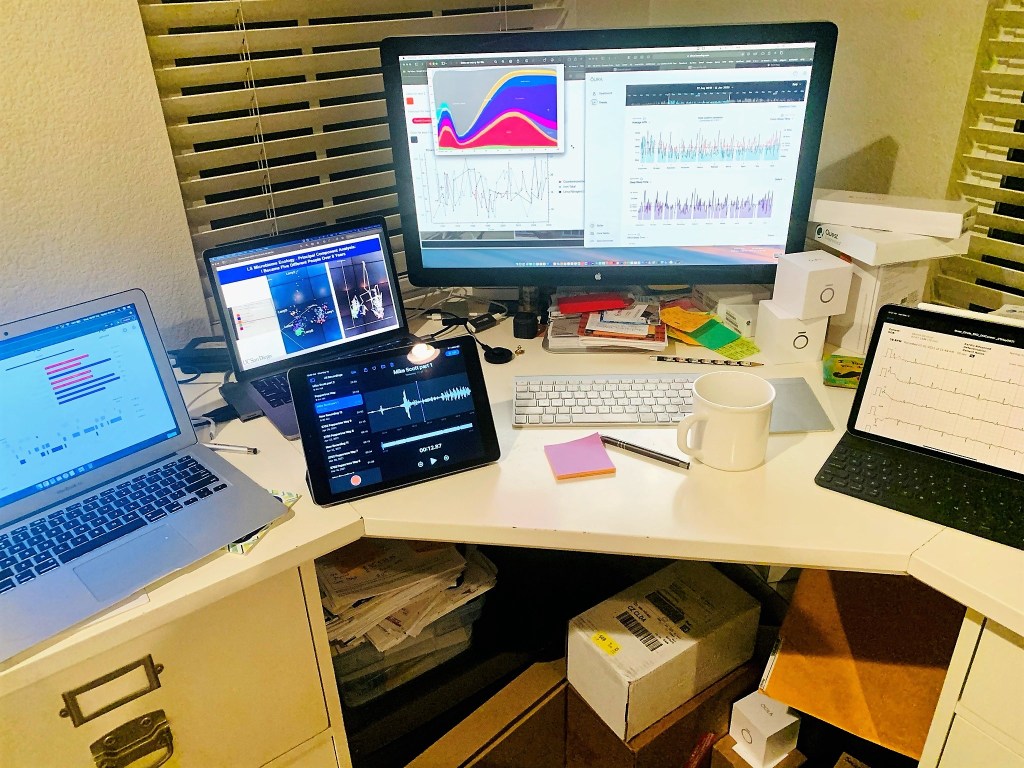

From his own home, Kurisu logs on regularly to check patient data at what he calls “Command Central”: three laptops, two giant monitors and one iPad.

“I have the dashboard of data from a particular wearable device,” he said. “Then I have another screen where I’ll bring up the electronic medical record. And then another one where I can communicate directly with the patient, and, you know, another that’s just for telemedicine.”

Tracking patient data through wearables falls into a broader category of what many providers call precision medicine, which includes genome sequencing to hunt for data-based clues to disease. Still, it may be a little early to depend on data from smart watches and rings.

“We’re going to be making a whole bunch of spurious associations, or thinking that the data mean something that they don’t,” said Dr. DeAunne Denmark, a neuroscientist and geneticist affiliated with the California community practice Altum Medical. “And we constantly need to be on the lookout for that. If the signal looks too good to be true, then it probably is.”

The coming years will likely provide more answers and published studies on the utility of patient data, and Denmark is looking forward to it.

“My feeling is, let’s collect as much data as we can on the people we can do it for and start asking these questions,” Denmark said. “What is the value of doing this? How many adverse outcomes can we prevent? Can we get a better idea for people earlier about what sorts of interventions they can start doing so that they don’t end up with a bigger event down the line that is more costly and more impactful?”

Later in his day, Dr. Michael Kurisu pulls up to the home of another patient, Tyler Orion. She has mobility issues. This being Southern California, they opt to conduct the appointment in her backyard, next to her tomato and collard plants. Dr. Mike is pleased with her data.

“I see you’ve been keeping your swims up,” Kurisu said.

“Oh yeah, and I love it when I get an attaboy from you when I finish,” Orion said. “I finish my swim and I immediately get a text from Mike that has something cute.”

For all the smiles, Kurisu’s venture faces an iffy future. Medicare could reduce payments for home visits and telemedicine when the pandemic subsides, and private insurance companies could follow suit.

For now, though, this doc says house calls, and virtual house calls, are good for him.

“I’m getting more deep sleep. I mean, here and there. I still have two young boys, so that remains to be seen.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.

It’s the last day of our March Fundraiser. Every donation makes a difference.

It’s the last day of our March Fundraiser. Every donation makes a difference.