How do song royalties for live performances work?

This is just one of the stories from our “I’ve Always Wondered” series, where we tackle all of your questions about the world of business, no matter how big or small. Ever wondered if recycling is worth it? Or how store brands stack up against name brands? Check out more from the series here.

Listener Paul Lusnia from Santa Rosa, California, asked:

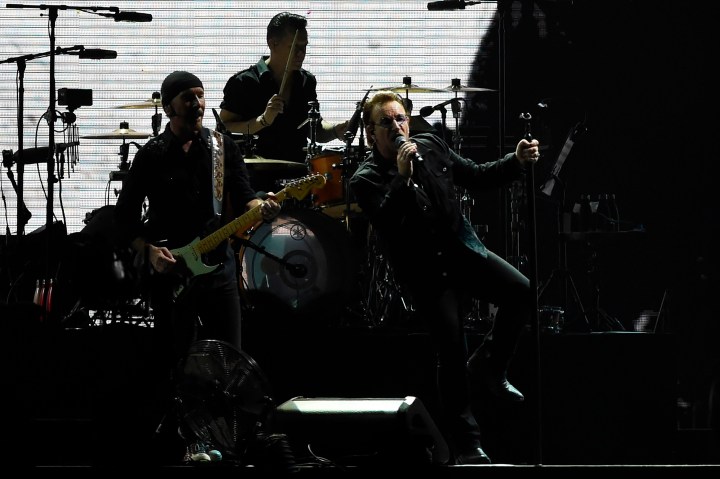

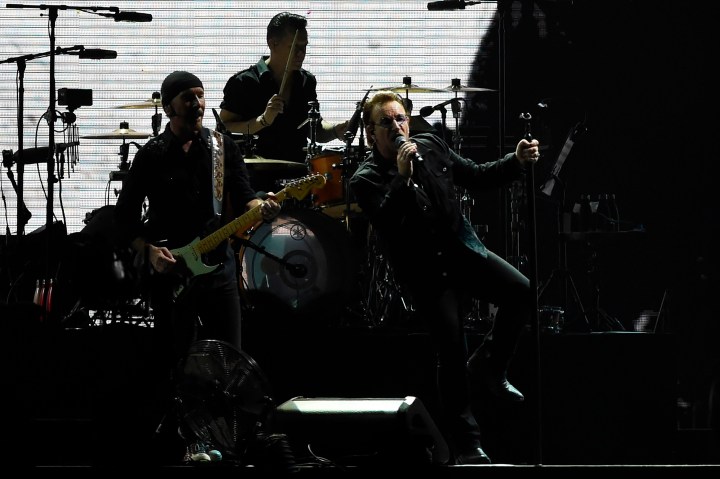

How do “royalties” for music (songs) work? I used to attend many live shows and often would see bands play other bands’ songs live, for example I saw U2 play a portion of Lou Reed’s “Sweet Jane.” If they do so, do they owe the other artist/band money for doing so? Also, do they need permission to do so before performing the song? If an artist sells the rights of their own music, then tours, do they have to pay for the right to play their own songs? Do songs eventually go into public domain like books?

Even when artists pay homage to other artists, there’s a price tag.

Songs and the rules governing the right to use them can get complicated really quickly — there are several different types of royalties spanning music on streaming services, social media and stages.

In the world of live performances, as Lusnia pointed out, artists will often do cover songs. (BBC Radio has a “Live Lounge” segment dedicated to this very premise.)

Here’s how it works. Almost all artists are signed with a music publishing company — prominent publishers in the industry include Warner Chappell, BMG, Sony, Kobalt and Universal, according to Don Franzen, a lawyer who specializes in entertainment and business law and is an adjunct professor with the music school at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Franzen said sometimes an artist will enter a deal in which the publisher controls the copyright and in turn makes a deal with a performance-rights organization like the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers or BMI.

These music societies, which represent copyright owners, then issue licenses to performing arts venues, like Walt Disney Concert Hall or Staples Center in Los Angeles.

Franzen added that the organizations have formulas for paying royalties to the songwriter and publisher. (The performer does not get a royalty unless he or she wrote the song.)

Venues pay an annual fee for a blanket public-performance license, granting them access to any of the society’s works, which can range into the millions.

Tobi Parks, the owner of a live music venue called xBk in Des Moines, Iowa, and a copyright and entertainment lawyer, said licensing costs are based on either your capacity or a percentage of your revenue.

An ASCAP spokesperson said that for its licenses, the rates can depend on how the music was performed, the size of the establishment and whether admission was charged. Licenses for smaller establishments, like bars and restaurants, generally cost about $2 or $3 per day.

The fee they collect, known as the public-performance royalty, applies to live venues, bars, restaurants, television networks and radio stations, said Benom Plumb, the program director for music industry studies and music management at University of the Pacific.

Plumb, who served as vice president of licensing at Bluewater Music, said it’s the venue that pays the fee, not the artists themselves. He noted that music publishers and their songwriters will affiliate with a society, register their song into the organization’s system and let them know what percentage of the song they own.

This would also apply when an artist is performing her or his “own” song, whose rights belong to someone else. The venue they’re playing should already have a license in place, giving him or her the right to perform the song.

Payment for performance

The amount a songwriter and publisher get paid for an artist’s live performance can vary wildly, with some songs garnering a couple of bucks or hundreds of dollars. Plumb said the two generally split this income 50-50.

He recalled that he represented a songwriter who wrote a hit for a well-known artist who played that song every night of a big summer arena tour. He registered the song for each of those performances with ASCAP and input information such as the date it was played, the size of the venue and the admission fee.

“When you register those songs for the live performances, then they know the song’s already in their system, they know it was performed at this place, and then they run it through whatever crazy royalty formulas they have. And then they pay that out in their next distribution,” Plumb said.

Plumb said that on the low end of the spectrum, a $2 to $10 royalty per song is common for smaller venue performances. But in the summer arena tour example, Plumb said he was looking at hundreds of dollars per performance, adding up to around $5,000 for the entire tour.

Questions and reform

One of the tricky things about royalties is that different music societies might represent a single song.

“If that song that was performed in your venue is partially represented by the [Society of European Stage Authors and Composers], then you’ve infringed, technically, on the public performance right of the SESAC portion, but not the ASCAP and BMI portion,” Plumb said.

Plumb thinks the licensing process should be streamlined and business owners should be educated about how it works.

“The problem with this publishing stuff, with these royalties, is that the amount that you get is dependent on the percentage of the song that you claim,” Plumb said. “It’s not very transparent, and they don’t really give you answers as to why you get paid what you get paid.”

Parks, of xBk, echoed those sentiments and said there may be entrepreneurs who don’t quite understand what they’re paying for.

In an emailed statement, ASCAP said it is “fully committed to transparency.”

“We recently launched Songview with BMI, a comprehensive data platform that provides music users with an authoritative view of copyright ownership and administration shares in the vast majority of music licensed in the United States,” the spokesperson said.

Parks said venues are paying for a blanket license for millions of compositions, but they might only use a handful of those songs. She would like to see a process where venues can report what’s actually being performed in their rooms.

“Most of the [performing-rights organizations] have a mechanism where artists can go in and enter their playlists, wherever they’ve been touring from, and the [PROs] come up with some kind of calculation and pay them a royalty,” Parks said. “But that’s up to the artist to manually enter that data.”

An economic downturn

The COVID-19 crisis was particularly challenging for the music industry, shutting down many venues.

“COVID really exposed how at risk and fragile the live music industry is, not only for venues — but for the performers that are making their living in our venues,” Parks said.

Parks said she understands that venues need to have licenses, but wonders whether the methodologies that performance-rights organizations are using to calculate royalties is optimal, given that shows have been on hold for so long.

In a statement, the ASCAP spokesperson said: “We view venues as our partners and understand how the pandemic has affected many of their businesses. Venues were not charged a license fee for periods they were closed and we made accommodations if they were operating at reduced capacity or without live music.”

Public domain

Like books, songs enter the public domain. Their copyrights expire eventually, decades after they were published. Back on Jan. 1, 2019, copyrighted works from 1923 began entering the domain — the first time works had done so in two decades.

Since then, a new batch has entered the public domain each year. All music, film and literature published in 1924 entered the domain in 2020, and all works from 1925 entered in 2021. That will continue as the years go by.

Why the gap? Previously, published material from 1923 was supposed to enter the public domain in 1999, instead of 2019. But in 1998, Congress passed a bill that extended copyright protections for 20 years.

Now, we’re finally getting the chance to use this material. In 2021, music by George and Ira Gershwin became available, along with lots of jazz music, “The Great Gatsby” and a trove of early 20th century American creativity.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.