Would you take a 1 in 1,000 chance to own a real Warhol drawing?

Would you take a 1 in 1,000 chance to own a real Warhol drawing?

A New York-based art collective called MSCHF — pronounced like the word “mischief” — made headlines recently for a project they dubbed the Museum of Forgeries.

MSCHF says it acquired an early sketch by artist Andy Warhol, made 999 copies of it, mixed in the real drawing with the fakes, then sold all 1,000 without knowing which was the real Warhol sketch, “Fairies.”

Undermining a Warhol artwork’s value via its perceived authenticity and scarcity might not have offended the late pop artist, according to art critic and Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik.

Gopnik recently spoke with “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio about the Museum of Forgeries project, what Warhol’s reaction to it might have been and ultimately how MSCHF’s attempt to undermine the idea of artistic authenticity may have only reinforced it. Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: Help me understand this. So this group got ahold of a real Warhol, and they figured out [how] to make, like, supergood copies?

Blake Gopnik: Yeah. Let’s be careful to say they “claim.” You know, they’re radical artists, they’re not members of the Better Business Bureau, so you have to take everything they do with a grain of salt. But yeah, they claim they bought this $20,000 Andy Warhol drawing, they say it’s from 1954, but they’re probably wrong. I found out it’s probably from 1958. It’s a picture of a bunch of fairies playing skip rope, and then they had a robot arm copy it 999 times, or that’s what they claim they did. Then they distressed all of those copies so they looked exactly like the original. They shuffled those 999 copies and the one original into one big pile, and they claim they don’t even know, you know, which is the original now and which are the copies. And then they sold all 1,000 for $250 each, and now they’re sold out, actually, or so again they claim. Which means they made a nice, little profit, right, $250,000 and spent $20,000 on the drawing.

Brancaccio: Yeah, if this is all true. But also, I guess, for the buyer, there was about a 1 in 1,000 chance that they got a real Warhol.

Gopnik: Yeah, but I guess I’d say, you know, do you want the real Warhol, which is, you know, kind of a semitrivial object, right? It’s a Warhol from the 1950s, before he becomes an important artist. Or do you actually want one of the copies, which is an interesting work of 21st century conceptual art?

Brancaccio: That is something Blake Gopnik would say. And, you know, we don’t have Andy Warhol around to ask his opinion to this, but he might not be — having read your biography of the man — he might not be totally offended.

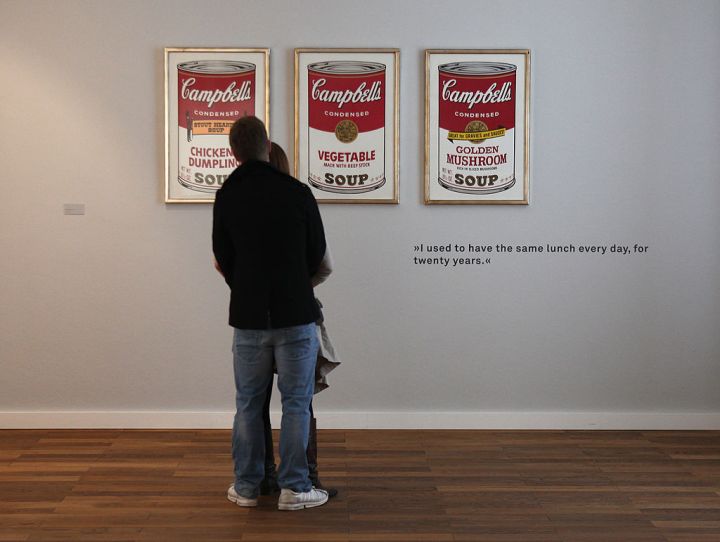

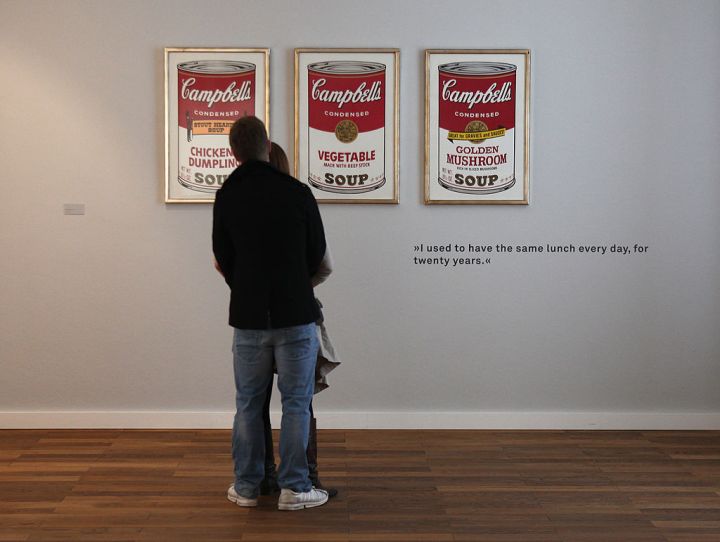

Gopnik: No. A lot of his art, once he started making pop art, a lot of the art is about, you know, reproducing things, about making silk-screens that, you know, can be made, at least similarly, again and again. The kind of funny thing is that in order to make their piece, this collective from Brooklyn, it’s called MSCHF, but they actually had to use an early Warhol when he was still a hand maker of art objects because that’s what they needed in order to make their project mean anything. If they used one of his late silk-screens, right, it already is something that’s about mass production, so it wouldn’t work. They needed something that was obviously handmade so that their robotic reproductions of it could be in a sense sufficiently different from that original.

Brancaccio: Yeah. I mean, and when Warhol was alive, even some of his acolytes were trying to use the silk-screens to make copies of Warhol, sometimes without his permission.

Gopnik: Yeah, occasionally. Probably not as often as people say. I mean, one of the funny things about Warhol is people always imagined that he actually mass-produced things, but he really didn’t. He pretended to, but really, his studio was like any other artist’s studio, it was pretty artisanal. Most of those, you know, silk-screen paintings were actually made by hand, by his hands. But he was talking about mass production, and that’s what MSCHF is doing too.

Brancaccio: And you love thinking about this, right Blake? This whole idea of, is it worth more or less, if somehow it’s a copy or a digital representation?

Gopnik: Yeah, I mean, it’s funny, you know. MSCHF says that their piece is very much about the fact that the art world, that collectors, care more about having a work that’s really just a commodity, that’s in limited supply, that, you know, exists in a copy of one, than they do about the aesthetics of the object. But I actually am thinking a different way these days. I think their piece actually reinforces the idea that authenticity matters. After all, it’s built on the idea that this one drawing isn’t original and that they make copies of it. If it didn’t have that magical status of the original, their whole project would be meaningless. If they had chosen, you know, the label from a jam jar and copied that 999 times, their project wouldn’t have meant anything at all. They had to be invested in this notion of the unique original in a way for their project to mean anything at all.

Brancaccio: It’s also, I suppose, another reminder that it’s not just about how an artwork looks, right?

Gopnik: Yeah. MSCHF is kind of up in arms that people care about things other than what they themselves called the aesthetics of the object. But in fact, the aesthetics are always a kind of small part of what an object is about. There’s always what I call an information cloud that floats around every object and really tells us what it means. I mean, that’s especially true today, right? In this age of Me Too and Black Lives Matter, we’ve discovered that who makes an object matters a whole lot. I mean, there’s a new show of works by this artist in New York, they’re videos of black men running through city streets. And the reason they’re especially meaningful is because they were made by a black woman, this woman called Steffani Jemison. If they were made by someone else, if we didn’t have that information about her, they mean something’s completely different. So the information about a work of art, like, for instance, that [it] was made by Warhol’s own hand rather than a robotic arm, that matters. That’s how art gets meaning.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.