Companies like Amazon spend millions on anti-union efforts. Where’s that money going?

Share Now on:

Companies like Amazon spend millions on anti-union efforts. Where’s that money going?

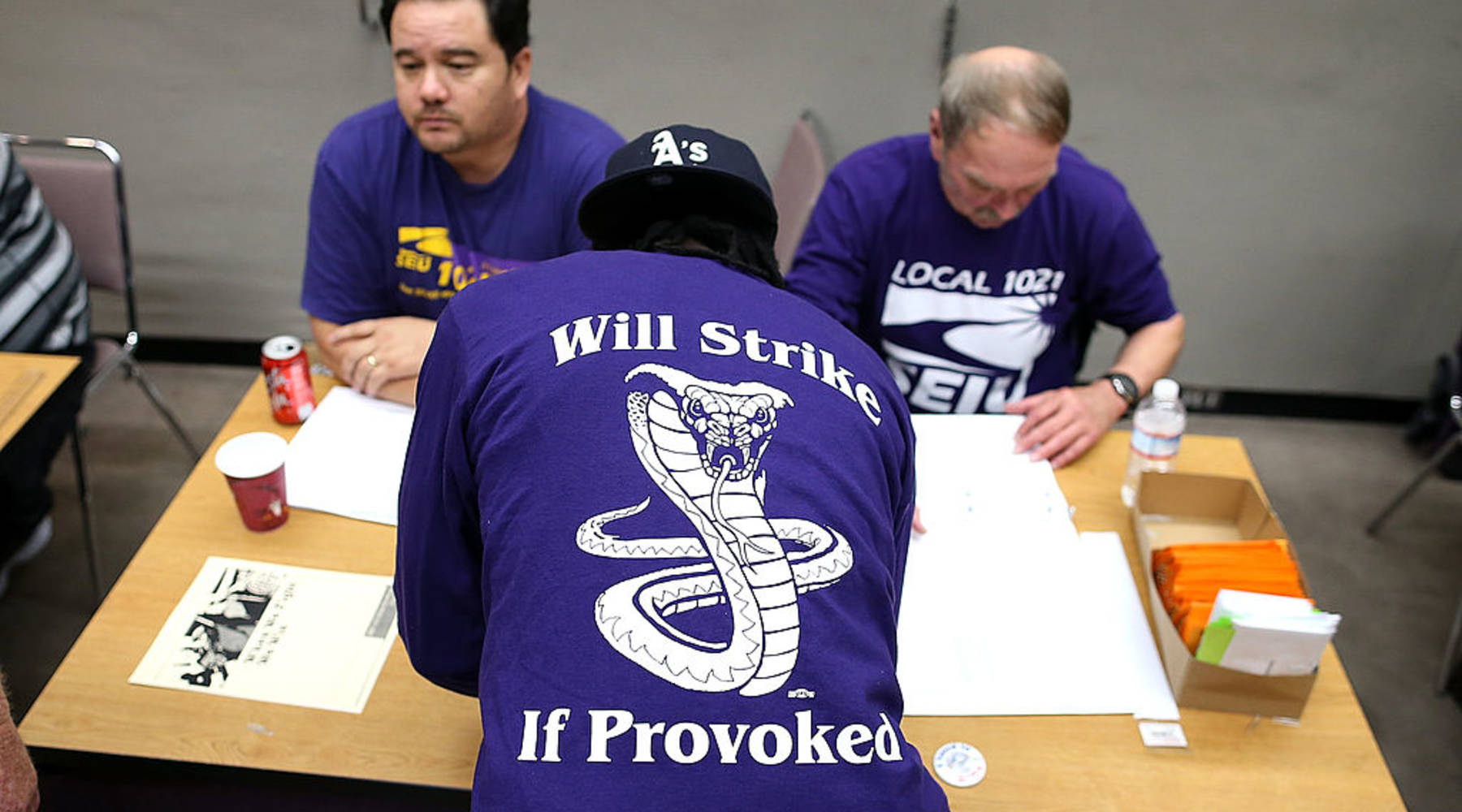

The millions of dollars companies spend on anti-union consultants haven’t been enough to stop some workers from unionizing.

This month, Amazon workers at a warehouse in Staten Island, New York, beat the odds and formed the first union in the retail giant’s history. Amazon spent nearly $4.3 million in 2021 on labor consulting firms to fight unionization efforts, according to filings with the U.S. Department of Labor.

By unionizing, Amazon employees are fighting for higher wages and better conditions, which would include longer breaks, paid sick leave and paid time off work for injuries. These moves may cut into the company’s profits and give workers a greater voice in decision making.

Although membership has declined to record lows, with the private-sector rate dropping to 6.1% in 2021, unions have gained growing support from the public. Sixty-eight percent of Americans approve of labor unions, the highest rate since 1965, according to a 2021 survey from Gallup.

Strong unions push for higher wages and benefits that can ultimately improve workers’ lives across the economy — even if they’re not unionized.

A coalition of investors has also advised Starbucks — which is seeing a wave of unionization — to remain neutral in response to these efforts because of growing public support, CNBC reported.

President Joe Biden himself has encouraged unionization, saying he intends to be “the most pro-union president” in U.S. history.

“The choice to join a union belongs to workers alone,” Biden said at a national trade union conference last week. “By the way, Amazon, here we come. Watch.”

What are companies spending this money on?

Employers spend about $340 million a year on consultants to prevent union elections, according to a 2019 report from the Economic Policy Institute.

Laboratory Corp. of America spent $4.3 million on these efforts between 2014 and 2018, while FedEx spent $837,000 over the same period and Quest Diagnostics (one of America’s largest COVID-19 testing companies) spent $200,000 between 2015 and 2017. The EPI also found that consultants can get paid $350-plus an hour or $2,500-plus a day.

Amazon, Labcorp, Quest and FedEx did not return requests for comment by publication time.

Jeffrey Hirsch, a law professor at the University of North Carolina, said that consultants help craft and implement the anti-union messaging deployed by companies. Companies will make presentations against unionizing, train managers on what to say and put up posters, among other tactics. He said you can almost think of these anti-union efforts as a political campaign.

Legal advice is one of the most costly expenses, he noted.

“You’re hiring attorneys who specialize in this work, giving advice to companies about what they can do, what they can’t do,” Hirsch said. “Or, to be perfectly blunt, sometimes I think even what you can’t do — but you might want to do anyway.”

That’s because companies incur “significantly lower fines” for labor violations than for financial and corporate law violations, according to the EPI.

One frequent component of anti-union campaigns is captive audience meetings, which are mandatory events during which employers or consultants discourage employees from unionizing.

“Sometimes these meetings can skirt the law with implied threats,” explained Joshua Freeman, a history professor at the City University of New York’s School of Labor and Urban Studies.

Freeman said a common phrase you might hear is: “We can’t afford to keep this place open if it goes union.”

Labor experts say the tactics these companies use are often taken from the same tried-and-true playbook.

“This is one of the reasons why you almost wonder why they get consultants because it’s sort of obvious the kinds of things to do — many of which are still quite effective,” said Adrienne Eaton, dean of the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations.

Profits, power and control

With all the money that companies spend on anti-union consultants, why not just let workers unionize?

That’s a question that Eaton also sometimes asks herself, although she pointed out that not all companies engage in the practice.

“Some employers will reach agreements with unions to be neutral in the election, or to not have an election, but just recognize the union with a simple card check,” Eaton said. Through card checks, unions are entitled to recognition if a majority of workers sign cards indicating they want to be represented by one.

She pointed out that while Amazon spent at least $4.3 million, the retail giant has more than 1 million employees in the U.S. That’s roughly equivalent to $4 per employee — a drop in the bucket for the company. “It looks like a lot of money, but actually it’s probably not given the size of Amazon,” Eaton said.

In 2021, Amazon raked in nearly $470 billion in revenue.

Freeman said unionized workers, compared to nonunion workers in similar jobs, generally make more money and reap greater benefits. Those benefits can include greater access to health care and retirement plans.

“A lot of unionists will argue that unionized workers are more efficient. So maybe some of those costs are returned to the company in terms of a more productive workforce, or a more loyal workforce, or a workforce with greater longevity,” Freeman said. “But it’s often the case that the wage bill goes up. And that’s going to come from someplace. If you can’t raise prices, it might reduce your profits.”

Many labor experts agree that there’s also an ideological component underpinning companies’ opposition to unionization, and that they’re concerned about losing control of their workforce.

“American employment law is very pro-employer. There are obviously some exceptions, but there’s a lot you can do without worrying about anything,” Hirsch said. “That changes pretty dramatically when a union comes in. In particular, you can’t make changes to the terms and conditions of work without bargaining with the union.”

Even without a financial cost-benefit analysis, Hirsch said, the “lack of unilateral control is a big, big deal for those who are running the company.”

Freeman said the heads of some big corporations have “a very particular ideological formation and psychology” and don’t want unions interfering with the way they run their business.

“They think, ‘I created my company because I’m a special genius. We live in a meritocracy. My success proves I know more, I’m better at this than other people,’” Freeman explained.

He pointed out that in the case of Starbucks, while some of the company’s outlets have started to unionize, many Starbucks stores run by other firms at hotels, airports and colleges are unionized.

“These companies would not be running Starbucks branches if they weren’t making money. I can guarantee you that,” Freeman said. “So we know for a fact that you can make money with a unionized workforce in a Starbucks.”

The future of unionization

After the Amazon Labor Union’s victory, organizer Christian Smalls, now the group’s president, said more than 50 warehouses have contacted the union.

Eaton said that while there’s excitement and elation about the drive at Amazon’s Staten Island warehouse, workers face a long haul to getting a contract, which can take years if it happens at all.

She said she hopes Amazon sees that having a successful business model is not incompatible with having a union.

Hirsch said, “Success breeds success,” with Starbucks being a recent example.

“It started with a couple stores in Buffalo [New York], and now it spread all across the country,” he said. “And I think that’s almost entirely because other employees are like, ‘Oh, wait a minute. Our colleagues elsewhere were able to do it. Maybe we can too.’”

Freeman said that in the history of American labor, unionization tends to come in spurts, not incrementally. He thinks that the victory at Amazon will encourage other attempts across the U.S. But he’s not sure how far they’ll get.

The Staten Island warehouse workers organized in a “very favorable political and cultural environment for unions,” he explained. New York has the second-highest unionization rate in the country, after Hawaii.

Although he’s not sure of the odds, Freeman said we could see “the beginning of what could turn into a new birth” of unionization.

“And that would be a big turning point in American economic and social history,” he said.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.