Is this what the “metaverse” looks like?

When Facebook rebranded itself as Meta in October, CEO Mark Zuckerberg described his vision for the “next chapter of the internet.” People would work, socialize, shop and live much of their lives in an immersive digital world called the metaverse.

Other tech giants, including Microsoft, Google and Apple — alongside video game companies, fashion brands, entertainment companies and numerous startups — have invested billions into metaverse technology and applications as well.

In an effort to better understand what could be the next evolution of the internet, “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal explored a virtual world with Rabindra “Robby” Ratan, an associate professor at Michigan State University’s department of media and information.

Using a Quest 2 virtual reality headset purchased from Meta for $299, Ryssdal met up with Ratan in a simulated conference room.

“Small movements,” Ratan said while explaining how to navigate. “You don’t want to vomit.”

This virtual conference room was created by a company called Engage, which advertises itself as a ”metaverse platform” for immersive meetings and events. “It’s one of many,” said Ratan.

“I think this is an uninformed question,” Ryssdal said. “How many metaverses are there?”

“I would say there are zero at this moment,” said Ratan, who has been studying virtual worlds for about two decades. “That’s kind of like the question, how many internets are there?” he said. “In the year 1988, there were zero. Maybe by ‘92, you would say, ‘OK, there’re some internets. There’s an internet forming.’ So this is like a little oasis in the three-dimensional internet.”

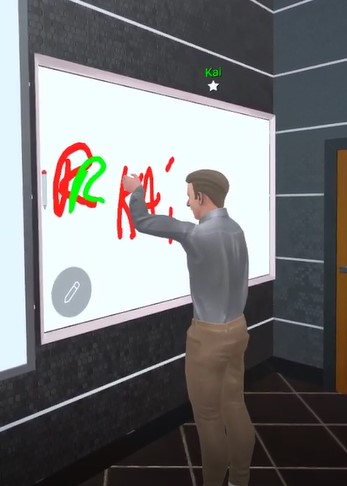

Ratan uses Engage regularly to meet with undergraduate college students for his classes in virtual reality. For Ryssdal, Ratan demonstrated drawing on a whiteboard and “spawning” virtual objects, such as a dinosaur skull.

In the screenshot on the left, a virtual Tyrannosaurus rex skull chomps on a computer-generated meeting attendee. At right, Ryssdal’s avatar draws on a whiteboard in virtual reality.

“I often will have my students spawn virtual objects like this, and we bring them up as a piece of our discussion,” he said. “For example, if it’s an architecture-related class, we could bring up buildings. People could bring things in that they design, we can look at them from different angles.”

Some observers say “metaverse” is essentially a marketing term used by companies building anything related to virtual and augmented reality or immersive digital environments. “One day, we’ll be able to just easily jump between these virtual platforms, [but] right now, you have to install it like an app on your phone,” Ratan said.

Within the Engage app, Ratan took Ryssdal to another, much bigger virtual space with multiple levels, seating areas and a stage.

Screenshots of a simulated “expo hall” on the immersive meeting and education platform Engage.

“This is actually one of my favorite places to hold class,” Ratan said. “I will have students set up in different booths and put together a small presentation. And then as a class, we move around and hear them present, but you could also imagine this for business meetings, of course. For conferences, any type of event convention.”

Ratan helped Ryssdal “spawn” a life-size virtual helicopter.

“Say we’re selling helicopters,” Ratan said. “I could, as you can tell, very easily create a helicopter for you to see … and fabricate pieces of equipment based on custom orders that people actually experience inside a virtual space like this.”

Between the hardware, software, events and advertising opportunities in virtual environments, Bloomberg Intelligence estimated that the metaverse could be an $800 billion market by 2024.

But Ratan said some of the economic potential of the metaverse lies in platforms becoming more interoperable, or easier to move between. Right now, it’s difficult to take digital possessions from platform to platform.

“Do you think the challenge is technology, or is the challenge scale, in getting wider adoption?” Ryssdal asked.

“Generally, when we’re looking at mass media, historically, the technology is the scale issue,” Ratan said. “We need to be able to standardize across the different technologies in order to produce at a low enough cost … and we also need them to be less of a walled garden.”

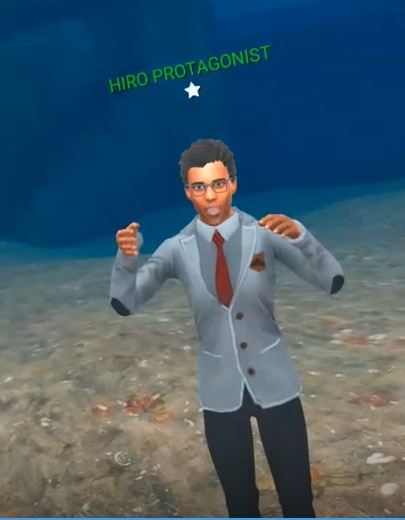

Ryssdal explores a simulated underwater environment in virtual reality with Rabindra Ratan, associate professor of media and information at Michigan State University.

In another virtual environment — meant to resemble the bottom of the ocean — Ratan and Ryssdal discussed the concept of avatar identities, or the visual representations of people in digital spaces.

“There’s this phenomenon called the Proteus effect, which is one of the main theories that I’ve studied as a media researcher,” Ratan said. “It’s the notion that when you use an avatar that has certain characteristics, it influences your behavior.”

For example, “if you use a taller avatar, you’ll negotiate more aggressively. If you use an avatar that’s more attractive, you’ll have more social confidence,” he said. “My favorite one: If you use an avatar that looks like an ‘inventor’ compared to a street-clothed avatar, you’ll actually come up with more creative ideas during brainstorming.”

Ratan’s own avatar, the one he used to speak with Ryssdal, is named Hiro Protagonist. That’s a reference to the 1992 science fiction novel “Snow Crash,” in which author Neal Stephenson coined the term “metaverse” to describe a 3D virtual world.

Ratan said he’s been using that name for about two decades. “I was just so inspired early on by these technologies.”

Although a 3D internet that seamlessly blends virtual and digital life is still science fiction in many ways, companies are already hosting virtual concerts, buying virtual real estate and creating merchandise specifically for the metaverse, which they’ll often call the Metaverse.

Ryssdal pointed out similarities to the film adaptation of another science fiction novel, “Ready Player One,” which takes place largely inside an immersive virtual reality video game. In terms of technology, Ratan said, “many pieces of that vision for the future are likely to be true.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.