Why University of California’s graduate workers are striking

Why University of California’s graduate workers are striking

On a regular weekday, Stephanie Redmond would be working in a neuroscience laboratory at the University of California San Francisco, trying to figure out what certain brain cells do – but, “that’s one of the questions that’s on hold right now,” she said.

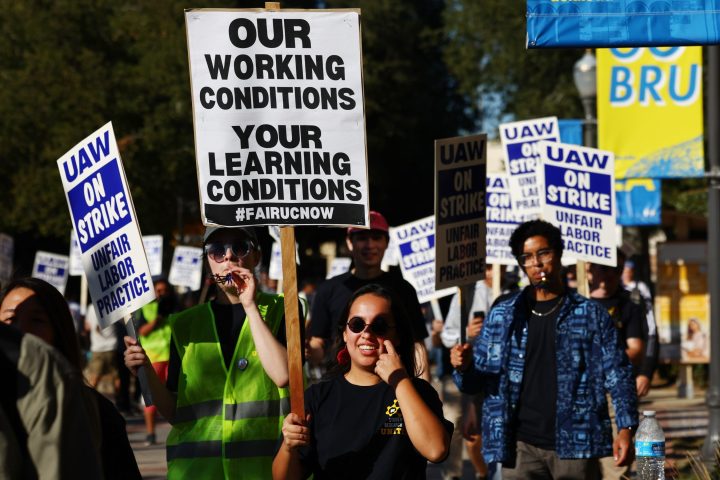

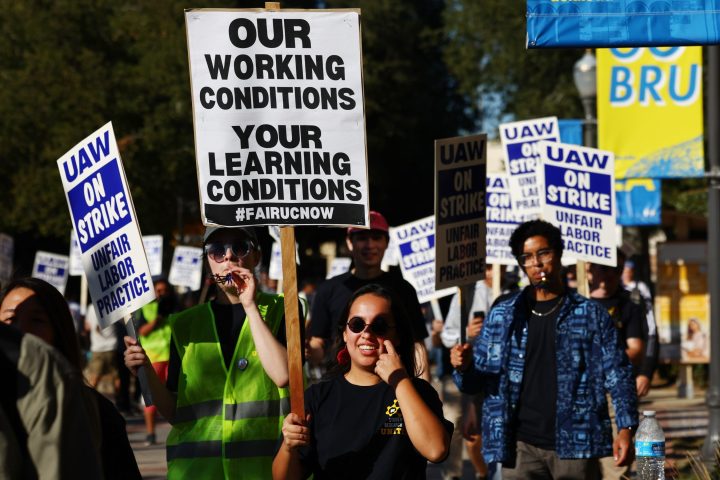

Redmond is one of the 48,000 academic workers in the University of California system who went on strike this week. Teaching assistants, tutors, and researchers didn’t show up for work in what organizers are calling the largest strike in the country’s history of higher ed. Workers say they’re not paid enough to live in the expensive locales where their schools are. Their demands include higher pay, subsidies for child care, and free public transit passes.

Redmond notes that the starting salary for postdoctoral scholars like her is about $56,000 at UCSF.

But in San Francisco, median rent on a one-bedroom apartment is over $3,000 a month.

Child care costs can run just as high. So, when Redmond had a baby, her family moved to a town 90 minutes away from the school.

“That’s how my family makes it work,” she said. “But it shouldn’t have to be like that.”

Organizers say that academic workers are an essential part of the UC system.

“We do the majority of teaching and research at the University of California. We grade papers, we teach classes, we teach sections, teach labs,” said Neal Sweeney, president of UAW Local 5810, the union that’s organizing the strike at UC, and a researcher in neuroscience.

The University of California said its working to try to minimize the effect of the strike on students, and that its proposed wages are near the top of the pay scale when compared to other public universities.

But, across the country, those wages are relatively low.

Dom Bouavichith was a graduate student who worked at the University of Michigan for six years, and is now a staff organizer for GEO 3550, a union that represents the graduate workers at the school.

“There’s a big misconception that because they’re students, they’re not workers,” said Bouavichith. “People really view graduate students as esoteric people who–the joy of learning is what’s driving them, not some sort of career path.”

One reason non-tenured academics are low-paid is that public colleges receive less government funding than they used to, says William A. Herbert, who studies collective bargaining among academics at Hunter College in New York.

“As a result that has caused there to be a push, trying to figure out ways to essentially save money,” he said.

Rutgers economist Paula Voos said many academic workers traditionally accepted lower pay in return for a chance to become tenured professors. But that tradeoff is not happening in the same way anymore.

“When it’s working well, it’s a kind of apprenticeship. Right now, it’s not working well in a lot of disciplines,” said Voos.

That’s partly because there are way fewer of those roles to apply for. According to the American Association of University Professors, less than half of all faculty positions in the U.S. are now on the tenure track.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.