How ‘Ivy’ clothes became a century-spanning fashion mainstay

How ‘Ivy’ clothes became a century-spanning fashion mainstay

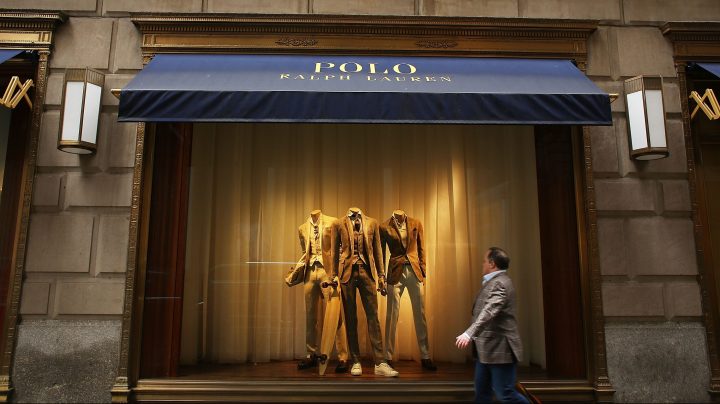

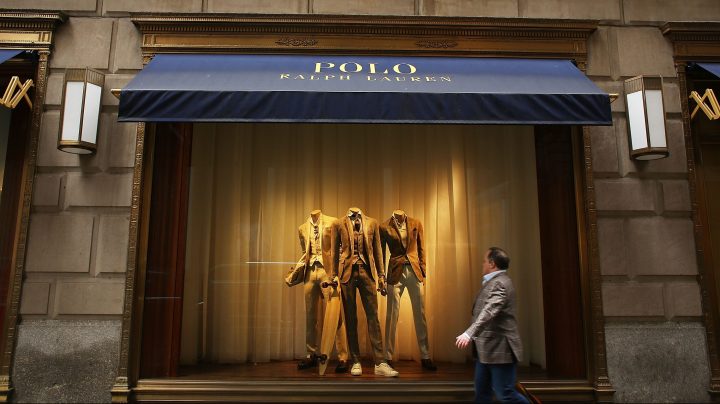

A Ralph Lauren polo shirt. A varsity jacket. Khakis and loafers. Are these clothes business casual? Date night attire? Is this a “preppy” look? As it happens, the answer is kind of all of the above, and it’s because they share a common fashion ancestor: Ivy.

Based on mid-century apparel worn on Ivy League campuses, Ivy is a fashion trend that’s stood the test of time. In her podcast, “Articles of Interest: American Ivy,” journalist Avery Trufelman traces the globetrotting history of the Ivy style, from its roots at Princeton University to its modern iterations by brands like Uniqlo.

Trufelman spoke with “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal about Ivy and its legacy today. The following is a transcript of their conversation.

Avery Trufelman: Ivy was a super duper huge clothing phenomenon in the mid-20th century. And over time, it evolved into what was in the ’70s and ’80s called “preppy style,” and what I argue now almost has no name at all. I mean, as menswear writer Derek Guy says on the program, you know, a button-down collared shirt is just a shirt. Khaki pants are just pants. But once upon a time, this was all part of a style known as Ivy.

Kai Ryssdal: Okay, so this is gonna get a little meta here, but this entire season kind of is — and as I said before we turned the microphones on, I don’t know exactly how this interview was gonna go — so I need to stop here for a minute and talk about this idea that you’re talking about in the first episode of this season about trends, because that kind of is what has happened here. Ivy was a thing, it became a trend, and now it is — correct me if I’m wrong — ubiquitous in what we wear.

Trufelman: Yeah, I think if you want to wear something to a job interview, if you want to look good on date night, this is a standard clothing style. You know, if we really trace the origins of where this comes from, it comes from the campus of Princeton, and it comes from Brooks Brothers. And it was once very much about looking white and looking rich and looking male. But this is where the study of trends comes in. In the 20th century, we went from wanting to look rich to wanting to look cool. And the weird thing about it is like preppy clothes have changed with all of these trends. If you track it over the 20th century, it really says so much about the state of American desire in this fascinating way.

Ryssdal: Which is really interesting, because the roots of what we see now as Ivy started in Japan.

Trufelman: Oh, yeah. Ivy was exported to Japan by this one guy named Kensuke Ishizu. And it really kickstarted the contemporary fashion industry in Japan, and Japanese brands then started to make American clothes better than American companies. And this is seen in very niche Japanese brands like a Evisu and Kapital, but most notably Uniqlo. If you look at it closely, is really doing an iteration of American mid-century preppy style, which they then exported and sold back to us. And we love it!

Ryssdal: We do. But on that idea of us loving it and trends growing and becoming everything everywhere all at once — not to mix my media, if you’ve seen the movie — somebody in one of your episodes says the thing about trends that is so corrosive is that they get so capitalized because this is it’s all a business and you got to make money. And that’s kind of why and how this happens.

Trufelman: It is why and how this happens. But I really think trends are, to some degree, innate in human nature. And yes, I think they can be corrupted by capitalism, just like love can be corrupted by capitalism, you know, for Hallmark Valentine’s Day cards. And I think at the same time that Ivy style, preppy style, basic style — whatever you want to call it — has been sort of propelled by trends across the decades. Weirdly enough, it is also a way of resisting trends. And one person I interviewed said, “You know, it is so cool, because it is so, so dorky.” And you look at pictures of like Miles Davis wearing button-down collared shirts looking so cool.

Ryssdal: He looks so good.

Trufelman: I mean, he looks so good. It’s like, the coolest way to be cool is by wearing dorky clothes and pulling them off. I think we’re seeing a return of Ivy style now, you know, I know the pandemic isn’t over, but as we’re sort of emerging from our pods and looking around, the simplest thing that you can always return to to make sure you look sort of baseline-acceptable is Ivy. It’s a trend that also resists trends.

Ryssdal: We’re kind of all reverting to the mean, right?

Trufelman: Yeah, in a way.

Ryssdal: This gets us chronologically out of order, but children of the ’70s and ’80s will not forgive me if I don’t mention the name Ralph Lauren here.

Trufelman: Oh, Ralph Lauren is a huge part of the story. I mean, Ralph Lauren began by working at Brooks Brothers. He was a salesman when he was like 20 years old for one year. And he sort of got an idea of what the style was, but he realized [the clothes] were sort of boxy. And he was like, what if I take this look and make it sort of body-conscious, make it sort of sleek? And he did that. He made an updated version of Ivy and really summoned in the era of the preppy by introducing the polo shirt to the canon of Ivy clothes. And one of my favorite fun facts is what we now call the polo shirt was truly a tennis shirt. It was invented by a tennis player. And now we call it after Ralph Lauren’s company, we call it after a different sport, which I think is very funny.

Ryssdal: At the end of this podcast, you sort of come clean a little bit. And you say, you know, you’d always thought of yourself as an outsider to this Ivy thing, but you looked around a little bit and discovered you you were actually in and of it. And I guess I wonder, can the rest of us — can we all get away from it if we wanted to?

Trufelman: I mean, it’s such an interesting thing, right? Because these clothes are so tied up with notions of class. And, yeah, I really had a reckoning at the end of it, which is that, you know, I went to prep school. And I really did not like this style, because I did not like what the private education system that I was a part of represented. And, you know, my theory that I have about it is that Ivy clothes represent everything that the Ivy institutions themselves are not: It is a relatively affordable, accessible look, that really is open to so many people. And it’s so potent. I mean, that’s why, you know, the far-right were wearing khakis and polo shirts at the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017. It’s because this was a look that communicated openness and friendliness and, you know, they sort of took that power of Ivy clothes and perverted it. But that’s the fascinating thing about these clothes. They really have a power to them that’s open to everyone — including me — and I realized instead of just denying it or trying to get away from it, maybe I should just embrace it.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.