Hurricane risk will grow in the coming decades, report warns

Hurricane risk will grow in the coming decades, report warns

In early October, Nina Migliaccio stood outside an emergency shelter in Venice, Florida, holding a black-and-white Chihuahua, Candy, and wondering how soon they’d be able to go home. In the aftermath of Hurricane Ian, Migliaccio had escaped her flooded and wind-battered house with her husband, Carl. A week later, she was still shaken thinking back to the storm.

“Oh, my God, I have chills,” she said, recalling the sound of the wind pounding against her large living room window. “Like pop-pop, pop-pop, pop-pop.”

She and Carl — both in their 70s — tried to brace the window with their bodies, she said, “because I think if this broke, we’re finished.”

That window eventually did break, along with two others. Their garage door was damaged, and parts of the roof were torn off.

“We cannot go back,” she said. “You must have a roof.”

It’s been five months since Hurricane Ian slammed into southwest Florida. More than 150 people died in the storm and its aftermath, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates the damage from high winds, storm surge and flooding at nearly $113 billion. The recovery is ongoing.

“It’s a slow process,” Migliaccio said when I called to check in with her this week.

Migliaccio was still waiting for workers to finish her new roof. Two broken windows had yet to be replaced. She was fighting with her insurance company to get reimbursed for a new garage door.

“If I have pocket money, I’d be doing so easy, but we don’t have pocket money,” she said. “We have living money, like most seniors.”

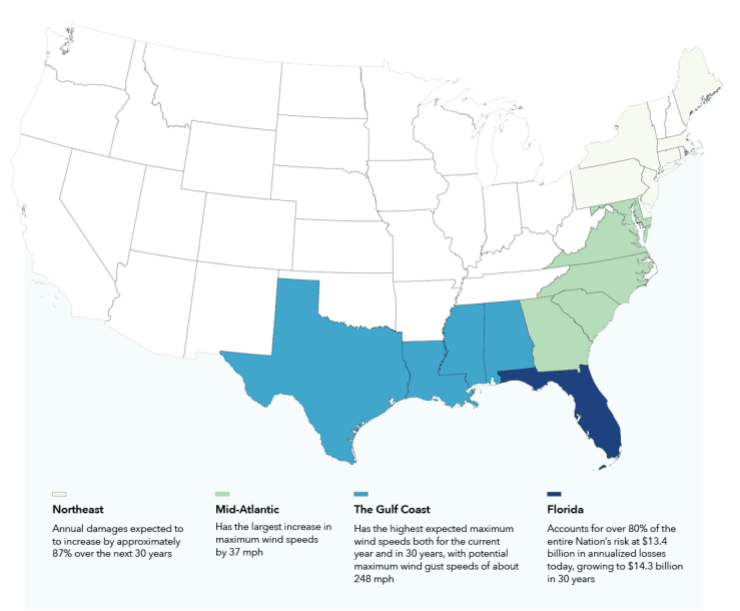

More people and properties will face this kind of damage in the future, according to a new report from the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit climate research and technology group. In the next 30 years, the report estimates, more than 13 million properties that aren’t currently exposed to tropical cyclones will be at risk. By 2053, the expected average annual loss from wind damage will grow by 7.5% to nearly $20 billion.

There are two main reasons for the increased risk, said Matthew Eby, the group’s founder and CEO.

“Overall, hurricanes are becoming much more intense,” he said.

Warmer sea surface temperatures lead to higher wind speeds, Eby said, and tropical cyclones will be more likely to become major hurricanes. In addition, “hurricanes are actually, latitudinally, moving further up north,” he added.

That means places like Brooklyn, New York, and Newport News, Virginia, will see big increases in maximum wind speeds and wind damage, the report found. Florida will remain the riskiest state, but Eby said hurricane danger will increase in northern cities like Jacksonville while actually declining a bit in South Florida.

“What you’re seeing across the state overall is an increase from $13 billion to $14 billion in average annualized losses, even though things are going down in certain areas,” Eby said.

Along with the report, the group launched a new tool this week on its website, RiskFactor.com. Type in any address in the country, and you can check out the risk of flooding, wildfire, extreme heat — and now wind. Based on factors like local building codes and the type and age of your roof, users can also view estimates of potential damage.

“The main thing we want people to do is know that there’s something you can do about this,” Eby said.

Understanding the risks can help homeowners make sure they have adequate insurance coverage, he said, “or do the appropriate resilience measures to harden your home.”

But will arming people with better information affect where they choose to live?

Daryl Fairweather is chief economist at Redfin, which has incorporated flood data from Risk Factor in its real estate listings for a few years. Last fall, the company published research showing that flood information did have some effect on behavior.

“People who were previously viewing extremely risky homes for flooding ended up buying homes with about half the risk that they originally were looking at,” she said.

Fairweather is a climate migrant herself, having moved from Washington state to Wisconsin after three summers of wildfire smoke kept her young children indoors.

“Every place has risks,” Fairweather said. “Where I am has high heat risk, but it didn’t have wildfire risk, it didn’t have hurricane risk, it didn’t really have flooding risks — so that definitely weighed on my decision of where to buy a home.”

Others are skeptical that climate information will significantly affect the housing market, pointing to recent increases in people moving to Western cities that face drought and wildfire risks and to hurricane-prone Florida.

There are just too many incentives that keep people living in harm’s way, said Robert Hartwig, professor of risk management and insurance at the University of South Carolina — including heavily subsidized insurance and government relief when disaster strikes.

“This is all very important information that I think that many individuals — but unfortunately, not the majority — will take into account,” Hartwig said. “Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that nothing, but nothing, will slow down the rapid economic growth we are seeing in some of the most vulnerable parts of the United States to climate change.”

For more on how people and communities are adapting to the climate crisis, check out our podcast “How We Survive.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.