AI lessons from the telephone operators of the 1920s

The rise of generative AI — and ChatGPT in particular — has raised a lot of alarm bells in some industries worried that the technology could make many humans’ jobs obsolete. And those concerns are real, especially for some research jobs like paralegal work.

But to give some context around what it could really look like for technology to transform jobs — or take them away — Dylan Matthews, senior correspondent at Vox, looked back at one such transformation that happened almost a century ago.

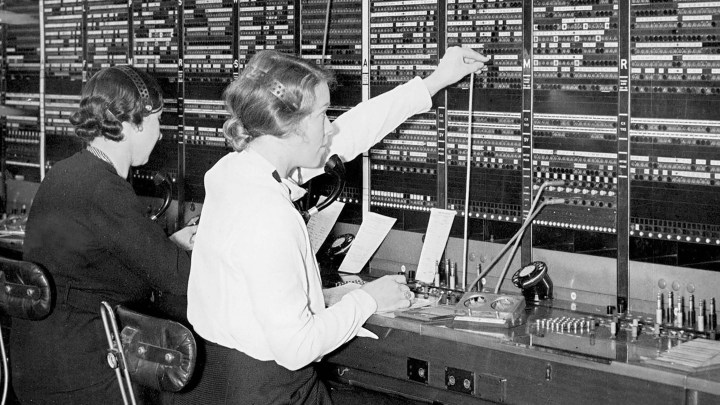

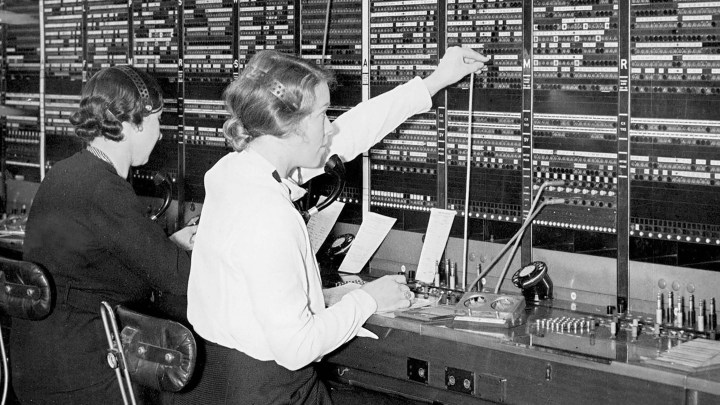

In the early 20th century, thousands of young women worked as telephone operators, taking calls and patching them through to their correct destination. But in the late 1920s, AT&T, which had a monopoly on the telephone wires, switched over to “mechanical switching” — and put thousands of women out of jobs in the process.

“Women who were already working as telephone operators, who were displaced by this — they really did suffer. They saw earnings losses in the near term, many of them dropped out of the workforce entirely,” Matthews said. “I think the lesson for people sort of coming up behind is that if you have enough time, it is possible to adjust.”

“Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal talked to Matthews about what the case of telephone operators can teach us about what AI could mean for jobs today. Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: So there you are in 1920s America, you’re a young woman. And if you are working, there’s a good chance that you’re a telephone operator. And then one day AT&T comes along, and what happens?

Dylan Matthews: So yeah, AT&T has a ton of power over this market. If you’re working as a telephone operator, and 160,000 women were, you were probably working for AT&T. And AT&T decides in the late 1920s to move over from individual women on switchboards to mechanical switching, which renders the human operators obsolete.

Ryssdal: So, walk me through the rest of the economy as the 20th century progresses, because this is not the only time that automation does what it does.

Matthews: Absolutely. So you and I are journalists, we’ve seen automation change our jobs rather dramatically. It used to be that the only way I could listen to “Marketplace” was on a radio, either in a car or at my house. Now, I can listen to it on my phone or I can listen to it via the internet. I mostly write text, and it used to be that that was a job that involved a lot of physical layout. You had people who were physically cutting and pasting text to make the layouts for newspapers. We’ve moved to digital, and that has automated a lot of work, but it’s also created a lot of other complementary work. And I think that’s the general pattern, is that most jobs aren’t automated away completely. Sometimes they shrink. There are fewer newspaper jobs than there used to be, there are fewer travel agents than there used to be, but they also evolve.

Ryssdal: So as we sit here on the cusp of yet another enormous technological change of AI and ChatGPT and all of that, draw some lessons. I mean, we’re summarizing a very long piece that you wrote in great detail in a four-minute radio interview or internet or what have you interview. Now what?

Matthews: So I think one lesson I take from this is that if automation sort of hits you square in the forehead, it can really hurt. So, women who were already working as telephone operators, who were displaced by this — they really did suffer. They saw earnings losses in the near term, many of them dropped out of the workforce entirely. And people who stayed in the workforce tended to get sort of worse-paying jobs. I think the lesson for people sort of coming up behind is that if you have enough time, it is possible to adjust. Women a few years younger mostly didn’t suffer because of this. This is an era where lunch counters and soda fountains started to sprout up, in part because you had this group of women who wanted to work. So one of my main takeaways from this is that, given enough time, the economy and people, in general, are quite resilient. But in the near term, it can be quite painful.

Ryssdal: Also, just to pull on that thread for a minute about when you happen to be born. Timing is everything, right? Because there are people whose jobs exist now, who will lose those jobs because of AI and all the rest of it. There are people who are going to be born in I don’t know, 3, 5, 8, 10 years, who will enter an economy where there’s just a whole different kind of jobs.

Matthews: Absolutely. I’ve started seeing a lot of job postings for a “prompt engineer.”

Ryssdal: I saw those the other day! It’s wild. It’s just amazing. There’s this new thing coming up. And ChatGPT has been around for like, what, half an hour practically?

Matthews: Right. And you can already get a job for using ChatGPT, not even making it but being the person who writes the prompts to get the best thing out of it. I don’t know if that job will be around forever. These things come and go. But as technologies come around, there are new possibilities that come with that. I think another thing to say here is that it can take some time for automation to take off. With telephone operation, it was very sudden when it happened. But they were using a technology that had been invented some 30 years before, it just wasn’t cost-effective for them to use until then. And similarly, there are hospitals and doctors right now who are using fax machines to do their work. And it’s not that they’re unaware that email exists, but it takes time and effort and money to transition. And so this won’t be immediate. And when they see the most starry-eyed proclamations of the world that AI will build, the point I tried to keep in mind is that it really relies on humans making that transition, and we’ll do so at our own pace.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.