A rebellious yell from the underclass

Econ Extra Credit’s film for September is the documentary “City of Gold.” In this week’s newsletter, we dive into the economics of punk. Subscribe here to get the whole series in your inbox.

The late Jonathan Gold was the first food critic to win a Pulitzer Prize, but he was also an exceptional music critic, and his music reviews were as unpretentious and inviting as his restaurant reviews.

“He didn’t write like a [music] critic would, which I mean as a high compliment,” former Spin editor Craig Marks told The Los Angeles Times. “He had an appreciation for the people who liked the band he was writing about, which is not the norm for writing about popular music.”

As a kid, Gold learned to play the cello, and he majored in music history at the University of California, Los Angeles. While Gold would write about opera, hair metal, avant-garde jazz, rap and hip-hop, he credited punk rock for bringing him “out of his shell.” He also played in several punk bands and even ran a punk venue known as the Anti-Club.

“Econ Extra Credit” spoke with Vivien Goldman, aka the punk professor, about how we can see the punk ethos seep into Gold’s writing. She is a London-born journalist, post-punk musician and author of several books, including “Revenge of the She-Punks: A Feminist Music History from Poly Styrene to Pussy Riot.”

This interview has been edited.

Vivien Goldman: I hadn’t quite realized how much of a real child of Los Angeles [Jonathan Gold] was, unlike so many people in L.A., which is a city of transplants in many senses. As I understand it, he was drawn to the world of classical music. And he found punk to be exactly what punk is designed to be, which is a fantastic liberator.

In my book, “Revenge of the She-Punks,” [I wrote] about punk as a liberator for women, but it also had the same effect for men. And let’s face it, without one we can’t really have the other. And so it was for Jonathan Gold. [Even when] he’d found a home in the more raucous and freewheeling world of punk, he did not turn his back on his classical roots. In fact, what is so particularly charming and very DIY about Jonathan is how he would go and jam on stage with his cello with punk bands.

What was unique about the punk scene in Los Angeles?

Goldman: Yeah, it was a very particular scene in L.A. I would argue, as the “punk professor,” that it was the most glamorous of punk scenes. A sort of inverted, trashy glamour, in contrast with a more political London scene and a more kind of self-consciously artistic New York scene.

When [Gold] ran a punk club, he had a more expansive view of punk than some people who get very territorial. He invited British groups like The Fall, with their singer, Mark E. Smith, to perform at his club. That was very subversive in a way by introducing this very different, grumpier, more beleaguered British sound into the lusher, plusher arena of L.A. punk.

It was very transgressive, the scene he was drawn to, groups like the Screamers and X, [and its] singer Exene [Cervenka]. They were bold, progressive, free thinking and very much more sort of dramatic or theatrical in their presentation. And I think this also has a connection with the fireworks in Gold’s own writing, which is very snazzy and compelling. He had a sort of vibrancy in his writing that is very dramatic, and the flow of it, you can feel that he’s been unleashed by the wisdom of punk rock.

Punk has many meanings to different types of artists, different mediums. Do you think there is a unified or shared definition for the ethos of punk?

Goldman: I think what links the many mansions of punk is that it is supposed to be a rebellious yell from the underclass, whose authenticity and rage may resonate in a way that when people first hear it, may not be comfortable. It can be uneasy listening.

And that is also why one of Gold’s big cultural breakthroughs was his championing of punk’s fellow protest music, rap and hip-hop. He wrote some definitive primary source articles on N.W.A. And it really shows his deep understanding of the two genres that are profoundly rebellious protest music.

There are a lot of anti-establishment, anti-corporate messages in punk. How do you define the economic worldview of punk music?

Goldman: When you look at punk and economics, one might consider when punk began. In England in the mid-’70s, we were having an oil crisis. There was general societal collapse. There was no electricity. People could sign on the dole [get welfare]. There was a lot of [house] squatting. And people weren’t always being kicked out of the squats.

It seemed like in this post-colonial, post-Second World War era, all the given assumptions about the developed world had just been blown up. That’s why that expression from the Sex Pistols, “Anarchy in the U.K.,” seemed relevant.

Now, what also happened was the existing systems of [music] distribution and production, they were all really controlled by multinationals with a kind of a reductive view of what would sell, and they weren’t keen on taking up this new rowdy music that was anti-establishment.

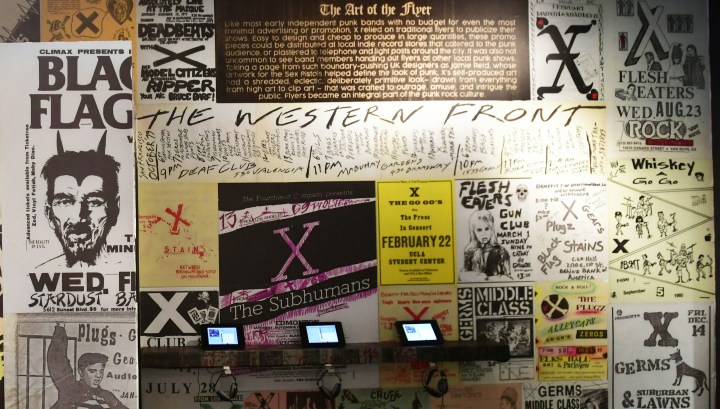

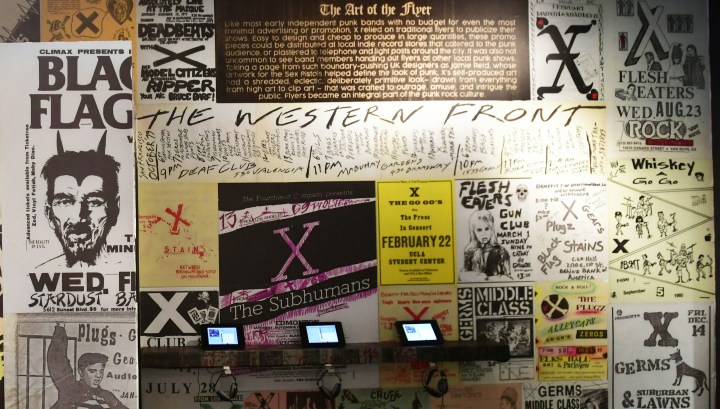

Punk, at its very essence, is a movement of do-it-yourself. So, punk kick-started an alternative sort of economy to disrupt the existing music business. Shops like Rough Trade developed an alternative distribution service. There was a band who on the album sleeve not only demystified how to play a chord, but also broke down how you could get your own record pressed. This was shattering all the mystery and mystique that had surrounded the commercial production of music. And that DIY is quintessentially punk.

Tipping: When we do it, how we do it, how much we do it

Going out for dinner in the U.S. usually comes with the expectation that you are going to pay a tip. (We hope at least 20%.) That’s been the status quo for decades, but a lot has changed in the restaurant industry in recent years. Since the pandemic began, the etiquette regarding how much to tip, and when, has become less clear-cut.

If you enjoyed our newsletters on “City of Gold,” we think you’ll also like “Marketplace Morning Report’s” series “Settling the Bill,” which explores the business of tipping. Listen to these stories to learn about the history of tipping, how expectations around it are changing and how it’s done in other countries.

- The tipped minimum wage has origins in slavery. That legacy means a worker can be paid as little as $2.13 an hour at the federal level.

- When — and how much — should I be tipping these days? Expectations around tipping have changed in the last several years. Here’s what to know.

- What does tipping look like in the United Kingdom? Free health care and a higher minimum wage in the U.K. means there’s less reliance on tips to make up workers’ income.

- A debate over tipping comes to South Korea: When a South Korean ride-hailing company started asking passengers for voluntary tips last month, it sparked backlash from some customers.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.