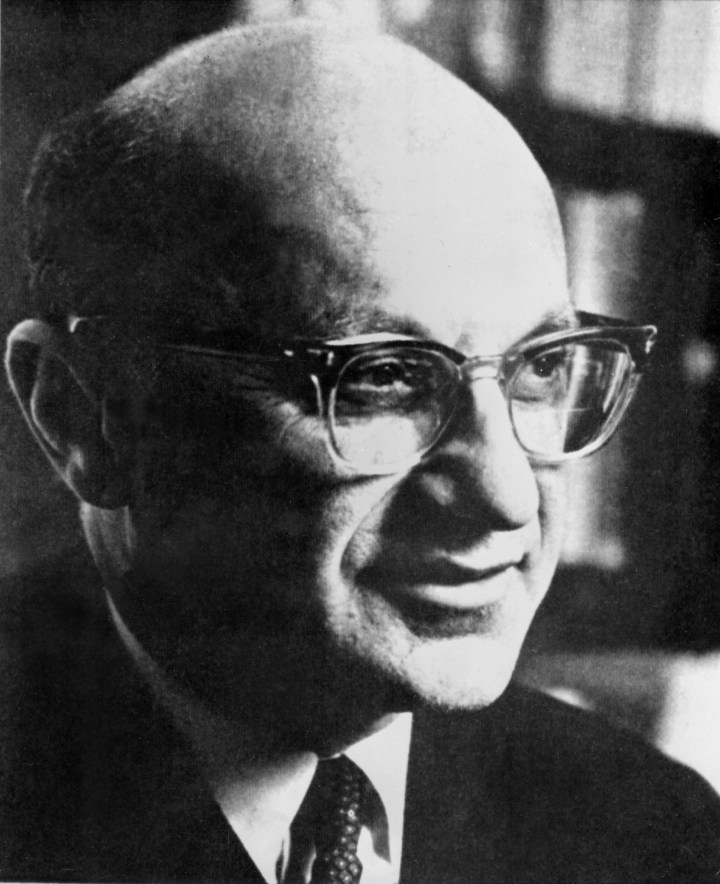

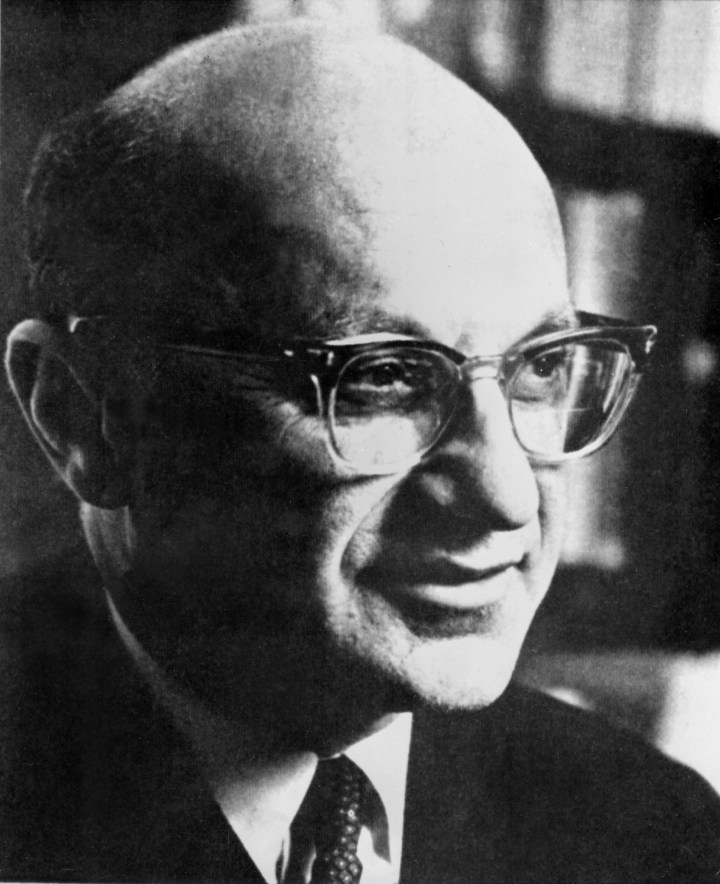

Are we still living in Milton Friedman’s economy?

Are we still living in Milton Friedman’s economy?

While campaigning for President in 2020, Joe Biden declared, “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore” in an interview with Politico. Yet 17 years after the economist’s death, many of the ideas Friedman wrote and talked about still shape current economic thought and policy.

Jennifer Burns is an associate professor of history and author of a new book called “Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative.” She spoke with “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal about Friedman’s life and legacy. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: Let me go to the subtitle of your book first. Why “The Last Conservative”?

Jennifer Burns: So, that’s a great question, and it’s one I get a lot because Friedman didn’t really identify himself as a conservative in his lifetime. But I have two ways in which I think that word is accurate to describe him. One is, throughout his life, he was not just an academic economist, he was someone who was very close to policymakers, ranging from Barry Goldwater to Richard Nixon, to Ronald Reagan. And all of those figures identified their politics as being part of the conservative movement. There’s a second reason though, which is, as an economist, Friedman really made his name by going back to older ideas of economics that the discipline was leaving behind. And he was, in that way, “conserving” the insights and discoveries of an earlier generation of economists. And the [word] “last” is really a gesture to the fact that the political synthesis Friedman represented —which was a combination of free market economics, strong national defense and a global orientation — is really coming apart at the seams in our current moment. So, I don’t actually know that he’s the last conservative of that type — I mean, I think there’s room for us all to find out — but I think it’s a question worth thinking over.

Ryssdal: Hold that thought on our current political environment and Milton Friedman, because that’s where I want to end. But this idea of him as “the last conservative” and going back to those values and conserving them, it also made him come off during his lifetime as a little bit of a contrarian, don’t you think?

Burns: It’s true. He was profoundly out of step, politically, intellectually and methodologically, with all his peers. And this was a moment when a number of economists with Jewish immigrant backgrounds like him poured into the academy and really reshaped the field. They all tended to be politically liberal and many of them were very much oriented around bringing new mathematical techniques and analyses into economics and making it more quantitative. And Friedman stood against all of this from his earliest days as an economist, and, as a result, he was incredibly unpopular, in part because economists thought, “Well, if it weren’t for this guy, Friedman, we would all be agreeing on everything, and we would have almost unlimited power because we would be able to stand up and in one voice tell politicians and policymakers what to do.” And every time they tried to do that, Friedman would pop up and say, “No, they’ve got it all wrong!” And so he really was quite disliked for much of his career.

Ryssdal: Let’s talk about, for a second, the two things he’s most known for now. One is the Chicago School of economic thought and theory and the other one is this idea of “monetarism.” And I know that before we turned the microphones on, I said that I need you to keep it high level here, but I do think we need to explain what Milton Friedman was about in economic theory.

Burns: So I guess I’ll start with monetarism. One easy way to summarize this is by Friedman’s famous dictum, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Monetarism really points to the role of money in the economy. And Friedman really developed this idea through the historical studies he did with Anna Schwartz. Specifically, their analysis of the Great Depression. They concluded what made the Great Depression “great” was a loss of one-third of the quantity of money in the United States over the course of the early years. And so they said, when you measure an economy’s health and activity, this really basic idea “How much money is there in the system?” is foundational.

Ryssdal: And we should also say here that Friedman and Anna Schwartz, his co-author about whom we’re going to talk in a minute, they basically said, “The Federal Reserve blew it during the Depression.”

Burns: Oh, yeah, absolutely. So, it’s interesting — if inflation is a monetary phenomenon, it’s also a political and an institutional phenomenon, because there were people who were supposed to support the quantity of money circulating in the economy. Those people were the Federal Reserve. [Friedman and Schwartz said] what they should have done is recognize this as a liquidity crisis, and flood as much money as they could into the banking system. Coincidentally — actually, not coincidentally, this is what policymakers do today, in large part because they have imbibed this lesson that Friedman and Schwartz discovered: That in the Great Depression, these extraordinary measures were not taken and the result was a decade or longer of economic depression.

Ryssdal: I mentioned Anna Schwartz a minute ago. Also, his wife, Rose. [Friedman] owes, and he kind of acknowledged it, but kind of, you know, rode their coattails as it were, the role of women in his life and how they helped him in his work. They were critical.

Burns: Yeah, absolutely. At every major publication, Friedman had or was working closely with a co-author or collaborator who was a woman. The most obvious is “A Monetary History of the United States,” because Schwartz was a co-author, although she really had to fight (and Friedman had to fight behind the scenes) for her to get proper credit for that book. But one of his technical works of economics, “Theory of the Consumption Function,” what I uncovered in my research, is this group of women economists — who studied consumption and who talked with Friedman about their ideas and their findings during summer vacations and over the years. These conversations grew more and more robust, more and more important to him and eventually, he wrote them up in a paper that then turned into the book. And so, that was basically a way for women — at a time when economics as a discipline wouldn’t really recognize their contribution — they almost planted their ideas with Friedman, and you know, saw them prosper and grow there.

Ryssdal: It’s — you talked about this in the book a little bit — the whole idea of “home economics.”

Burns: That’s right. It’s a great irony because women were considered to have expertise in buying, selling, shopping, these types of things. And so those were kind of left to the side [by male economists], that was women’s work. And over the course of the 20th century, how to support consumption (which is an essential part of demand) became really important to the political system and the economics profession. And so the people who knew the most about actual consumption — how real people, real families, made these decisions — were these women researchers who were often in low-prestige, low-paid jobs. And Friedman figured out how to use their findings and how to think the way they did. And then because he was a tenured professor, he was able to package these ideas in a way that really caught the attention of the broader profession.

Ryssdal: I want to talk about Milton Friedman, as you call him in the book, “the political figurehead.” His alignment with Goldwater, Nixon and Reagan. And now you progress through the Republican Party of today. I wonder, [if Friedman] were to come today and look around at the nominally Conservative Party in this country, what does he think?

Burns: So, one way to think about that is to understand that throughout his life, he saw himself as fighting a countercurrent in Republican politics and the conservative movement of populist and conspiratorially minded conservatives. So this started in the 1950s, when he saw himself as fighting what he called, “the McCarthy McCormick wing.” That was Joe McCarthy, the anti-communist senator and Robert McCormick, the publisher of the isolationist, Chicago Tribune. [Friedman] called them sometimes “the crackpot conservatives” of the radical fringe, and that was who he was hoping to displace. So I think he would see, you know, the current state of play today is that this is an old tendency. This is something that happens over and over again, and we can’t give in to the more populous and conspiratorially minded trends, we have to provide a better alternative.

Ryssdal: And then to the management of this economy today. I mean, Jay Powell, for crying out loud, I don’t know if you watch his press conferences, but pretty much every time, Powell [mentions] the long and variable lags of monetary policy and Joe Biden, in the 2020 campaign said, “Milton Friedman is not in charge anymore.” I mean, he’s still a presence in the management of this economy [years] after he died.

Burns: Yeah, that’s absolutely true. And just, you know, going back to my title, “the last conservative,” there’s a way in which he’s “the last conservative” because his ideas have become very important to liberals and to Democrats. They’ve kind of marked out a centrist liberalism, that, you know, is now under attack from a more progressively oriented members of the party. So, you know, I think when Joe Biden talks about Milton Friedman, it’s kind of gesturing to that divide within the Democratic Party. In terms of Jay Powell, I think that as inflation has emerged, Friedman has become an important figure, because he was really part of the first effort to tackle the great inflation in the 1970s. And so to talk about Friedman is to signal a certain position and to sort of call on his prestige and his credentials.

Ryssdal: When you look around in this economy today, what signs of Milton Friedman, do you still see in policies or programs?

Burns: So, beyond the inflation debate, I think it’s really interesting how pandemic relief was structured. It was really structured along the lines of the Earned Income Tax Credit, whether it was a child tax credit or some of the more direct relief. And this is what Friedman had been calling for, for most of his lifetime. And so I think that model of policy has become very ingrained, and become very natural and it was not at all in [Friedman’s] day. So that’s one thing I see.

Ryssdal: With all possible respect, this [book] is a tome. It is not light reading, as much as I enjoyed it. But what do you want people to know about Milton Friedman? And I’m going to ask you to answer that in like 45 seconds, but what’s it important for people to know about this guy?

Burns: What I really want them to know is that the Friedman you might see on YouTube, or hear about the you know, the last things he said in the ’90s and ’80s, is not the full Friedman. You really have to understand the young Friedman, and the Friedman, who lived through the Great Depression, lived through World War Two, lived through the crisis of stagflation and that his ideas really respond to those historical moments. And whether we agree with the conclusions he came to or not, we have a model of somebody thinking through his time and doing his best to use the intellectual tools and capacities he [had] to propose new solutions and new ideas.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.