How settlers abused financial guardianship in the Osage Nation

How settlers abused financial guardianship in the Osage Nation

Every month, “Marketplace Morning Report” watches one film with economic or money themes as part of our Econ Extra Credit project. For November, we’re watching “Killers of the Flower Moon,” which tells the story of the Osage Nation of Oklahoma in the early 20th century, and how its people were subject to exploitation and murder at the hands of settlers stealing their wealth.

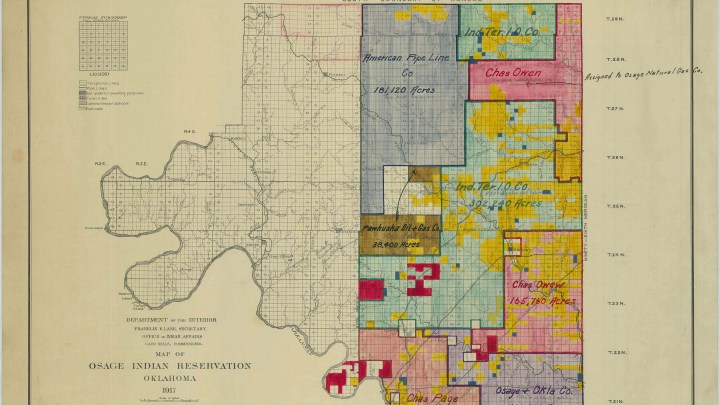

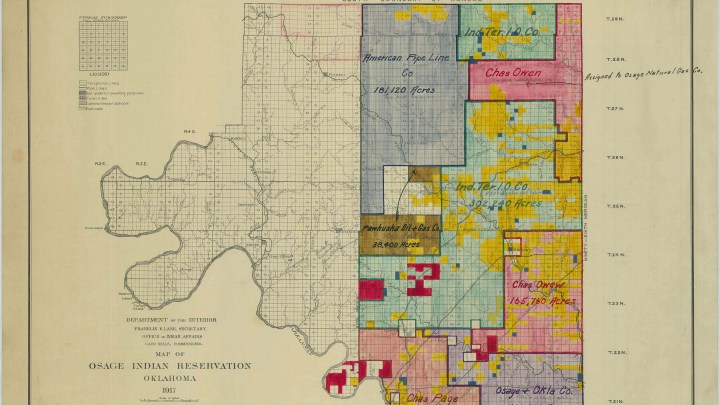

The Osage Indian Reservation was oil rich, and this led to immense wealth for the tribe. But, as the film depicts, Osages were actually restricted from managing or spending the money as they wished. Instead, financial guardians were put in charge of much of this money, because government policies deemed Osages unable to mange it themselves. And these financial guardianships were rife with corruption and theft.

Allison Herrera is a senior reporter for the investigative journalism outfit APM Reports, which is owned by the same parent company as Marketplace. She covers Indigenous Affairs, and her work can also be heard on the podcast from Bloomberg called “In Trust.” Herrera spoke with “Marketplace Morning Report” host Sabri Ben-Achour, and the following is an edited transcript of their interview.

Sabri Ben-Achour: There is this legal concept of “guardianship.” People might be familiar with this from the story of Britney Spears, after she fought to have her guardian removed a couple years ago. But this is basically somebody else being granted the authority to tell you how you can and cannot spend your money. It has a long legal history, which we see in “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Can you explain what we see there?

Allison Herrera: Yes, guardianships stem from this racist, paternalistic policy that was put in place by the federal government in the early 20th century that basically deemed Native people incompetent to run their own affairs and manage their own money. The policy was first implemented, ultimately, to protect Osages from being exploited by non-Indians, but it ended up not being that way. So in 1912, the United States government passed this law that said Osage citizens who are more than half blood were deemed incompetent. Or you may remember a scene from the film “Killers of the Flower Moon” where Mollie Burkhart has to go into the office and she has to read off her allotment number and say “incompetent.” And so that’s basically the system that people operated under. [Terry P. Wilson’s 1985 book, “The Underground Reservation,”] said that 18 years after the Osage Nation was allotted, white guardians were paid more than $8 million from their own Osage ward accounts. I haven’t adjusted that for inflation, but that’s a lot of money.

Ben-Achour: What kind of legal landscape developed around this?

Herrera: So that’s a really good question. And this goes back to Oklahoma statehood. There was an act that was put in place called the Oklahoma Enabling Act. And what this did was it made a lot of provisions and laws for Oklahoma to enter into the union. And the act laid out that in matters of Indian affairs, that was to be left between the federal government, because of the trust responsibility it has for tribal nations. But shortly after statehood, in 1907, you had all of these businessmen, these landowners, cattlemen, that lobbied really hard to give local courts and judges in eastern Oklahoma control over probates and wills and estates. And that allowed for judges to appoint their friends and family as guardians over these Osages. And in 1924, another congressional hearing that I read, it was held over headright payments and guardianships. And Chief Bacon Rind, the former chief of the Osage at that time, complained to the commissioner about guardianships and the payment restrictions, and said that it just unfairly put a target on Osages backs.

Ben-Achour: So, even in death, the access to wealth was kind of diverted, legally?

Herrera: Yes. I did some reporting about a woman named Lillie Morrell Burkhart. She was not related to Mollie Burkhart or the Kyle sisters. But this was in 1967. After she passed away, her will went into this lengthy probate in Osage County, and her then-divorced husband, Byron Burkhart, was able to claim that he was her common-law husband through the courts, and then was able to get a salary off of her estate. That the judge had said, “Yes, even though y’all were divorced, you were her common-law husband, and therefore you’re entitled to her salary and part of her belongings and part of her estate.” So, I mean, this isn’t something that was just in the 1920s. This was even later in the ’60s and ’70s.

Ben-Achour: A central figure in the film involved in the exploitation of the Osage tribe and land is William Hale. In the movie, he is played by Robert De Niro. He ends up going to prison for murder. And then there arises the question of who gets his land. The guardianship system is, again, a big part of that story arc. Can you explain how?

Herrera: Yeah, so his guardians were Roy Cecil and Fred Gentner Drummond, and Roy Cecil Drummond is the great-grandfather of the current Oklahoma Attorney General, Gentner Drummond, and rancher Ladd Drummond, who’s married to Food Network star Ree Drummond. They used money from a ward that they had named Myron Bangs Jr. Roy Cecil and his brother Fred Gentner were his financial guardians. And Fred Gentner, he ran this family store and he used $15,000 from Bangs Jr.’s account, that’s his ward, in payment for Hale’s land. And then he repaid it from another account.

So, Bangs Jr. fought to have this guardianship removed, because he felt that there was corruption going on. And this was a person that flew an airplane, he served in the U.S. Army. And so he hired this accountant to audit his books, and was partially successful in a lawsuit to have the Drummonds removed as his financial guardians. And so that’s how guardianships factored into the sale of Osage land. You know, people would borrow money from their wards’ accounts as a down payment for this really valuable ranching land.

Ben-Achour: Is there a legacy today of this guardianship system? Do Osages still talk about it?

Herrera: The policy of deeming someone incompetent because of their blood quantum is gone. But the subject is really painful to talk about. One woman I interviewed before the movie even came out, this was before the summer, she talked about how her mother was abused by her guardian. And there’s even a highway named after this particular guardian in Osage County.

Last week, I attended this event in Ponca City — that’s near the Osage reservation — where a friend of mine was giving a talk about the guardianship system. And the room was packed full of non-Native people. And I could hear people’s reactions of shock and awe when they heard about this system, you know, something that was about 100 years ago that people just still didn’t realize was happening in the state, in their county, to their neighbors. And so we were sitting in this fabulous, historic house built by an oil baron by the name of E. W. Marland, talking about guardians, and people were on the edge of their seats. So I think that the movie has prompted a lot of discussion about this racist policy, and I think people are starting to talk about it more openly.

Correction (Nov. 20, 2023): Previous versions of this story cited the wrong source for the $8 million figure that quantifies how much white guardians were paid from Osage ward accounts. That number comes from Terry P. Wilson’s 1985 book, “The Underground Reservation.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.