“It’s Jenga meets pick-up sticks, which meets slinky rubber band”

“It’s Jenga meets pick-up sticks, which meets slinky rubber band”

From a distance, the wreckage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore looks like a heap of Tinkertoys some kid spilled on the floor. But from a Coast Guard boat that’s doing a loop around the debris, the sheer size of it is overwhelming.

Giant steel trusses jut up at precarious angles, and, like an iceberg, there’s a lot more below the surface, including about a mile of interstate highway. There are at least 11 cranes visible, all on barges, with tugboats nearby moving that wreckage.

On the Coast Guard boat, Chief Petty Officer Johan Ulloa, part of the emergency response team, points out flames on one barge where workers are cutting the steel with torches.

“They’re trying to cut those pieces of bridge down into smaller sizes,” he said.

The Key Bridge created an estimated 50,000 tons of wreckage when it collapsed, blocking the Port of Baltimore from regular ship traffic. Since then, more than a thousand people have been involved with the recovery and salvage efforts around the fallen bridge. They include members of the Coast Guard, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Navy, as well as civilians from the salvage industry, like divers and crane operators.

Back on the water, one of those crane operators slowly pulls up a weight and then drops it like an anchor to pulverize parts of the bridge.

“They’re actually smashing it with that large weight,” Ulloa said. “So a lot of sophisticated tools being used, and then just some grit.”

“Yeah, basic physics,” added Senior Chief Petty Officer John Stephanos, who’s also in the Coast Guard. He pointed out another crane with a giant claw that drops into the water.

“Like an arcade claw game,” Stephanos said. “It’s going to reach down in, and based on what they’re pulling up, also based on sonar scans of the bottom … they’ll know which tool, which claw, to put on the end and roughly where to grab.”

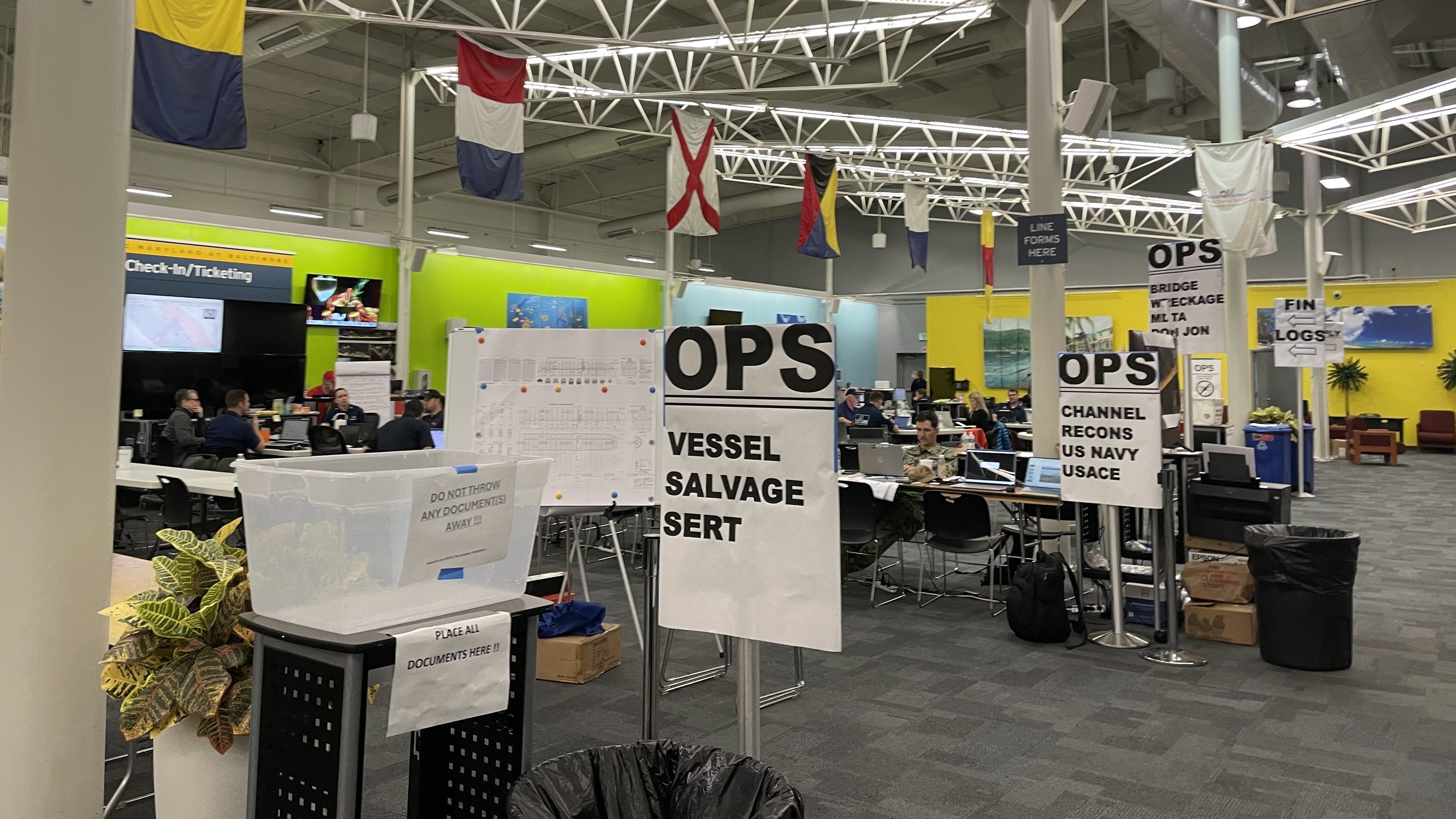

This is being planned at what’s usually the Maryland cruise terminal, which has been taken over as the incident command post. This means there are signs that say “missing luggage” next to giant diagrams of the Key Bridge.

One person working to clear the waterway is Col. Estee Pinchasin, commander of the Baltimore district of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. She said the work changes as they cut and move different parts of the bridge.

“It’s Jenga meets pick-up sticks, which meets slinky rubber band,” Pinchasin said, because there’s stored energy inside those giant bridge pieces.

“So, if you were to imagine holding a spring really tight, and then you’re pulling it apart, and then you cut it, it’s going to have a reaction. It’s going to snap back. You have that on massive steel members,” Pinchasin said.

To manage that snapback takes know-how from structural engineers and crane operators.

“You watch it, it looks so graceful, they’re just picking stuff up out of the water — there’s a lot to it. They can literally feel how the load is reacting,” Pinchasin said.

That’s where the planning comes in, said another leader of the salvage operation, Coast Guard Capt. David O’Connell.

“They go to the engineers and say, ‘Is this going to work?’ The engineers say, ‘Yes, we think that’s going to work,’ and then they do it, and hopefully it all works out,” said O’Connell. So far, everything has worked out, he said.

One big question is how much this is all going to cost, especially since there’s a timeline to clear the permanent shipping channel by the end of May.

“From our perspective, we’re just focused on the work,” O’Connell said. “I mean, obviously, it’s costing money, and people are working here, and they’re getting paid, and everything’s moving forward.”

O’Connell said there’s no model for dealing with this exact kind of disaster. So, the Coast Guard is using what it’s learned from previous crises to respond to one he calls unprecedented.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.