Nate DiMeo’s new book makes history feel like fiction

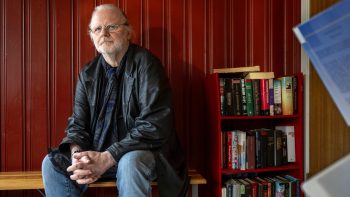

Nate DiMeo has long wanted to write a book based on his hit podcast, “The Memory Palace,” but the type of book he envisioned was always pretty specific.

“I would think about the books that I had as a kid, these sort of collections of short pieces,” said DiMeo, mentioning favorites like Shel Silverstein’s “Where the Sidewalk Ends.” “And I always wanted to collect stories from ‘The Memory Palace,’ and that might be like one of those books that don’t really exist for adults. And make one for adults, about adult concerns.”

Now, his new book, “The Memory Palace: True Short Stories of the Past” is a realization of that dream. As the title implies, it features short stories of both famous and not-so-famous people throughout history, often focusing on the moments that slip through the cracks.

DiMeo even turned the focus on his own life, including several chapters of his own family stories. The following is an excerpt from the book.

I spent my twenties in Providence. I lived on the bottom floor of a two-family house on the west side of the city, on the other side of the highway from downtown, and the other side of the tracks from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design and the homes of people who raised their kids to assume they could go to places like Brown or RISD. My mom grew up in that house. Her father did too. And when my grandfather died at eighty-six years old, his widow couldn’t take living there anymore. She couldn’t take sharing her space with the ghosts of days spent with her husband and their daughters, and with her husband’s family, and with herself as a young woman, ghosts that would appear in every corner. At the top of the stairs. At the sink by the window. In the empty side of the bed. So my grandmother moved out and I moved in.

I loved it. And not just because I was twenty-three and aimless and underemployed and got to live rent-free. I loved the house itself. When I was growing up, it had echoed with stories, endlessly re- peated at big Italian family dinners, and during the tail ends of Christmases, with the dying embers and the embarrassing uncle passed out on the maroon velour chair. For new audiences, the stories were stretched and embellished; for close family they were invoked, compressed like Mandarin proverbs until they could be summoned by a couple of brushstrokes: “Dad and the Studebaker,” “Mom’s Broken Finger,” “Janice Through the Bathroom Window.”

I loved those stories. Surely the reason I tell stories for a living is because I loved those stories. And despite the sheer volume and breadth of the memories that accumulate in a house in which one family had lived since 1914, most of the stories, and the ones retold most often, were drawn from a single era.

For several years, from the late 1930s until not long after the end of World War II, my grandfather ran a nightclub on the banks of the Pawtuxet River in Rhode Island. It started out as the Hi-Ho and was eventually rebranded as the Club Baghdad, complete with an oasis painted on the wall and a general Casablanca, certainly-offensive- today, Edward Said–y “Orientalism” vibe. They did a full revue: crooners, comedians, a midsize big band, showgirls, national tour- ing acts, regional mob bosses. My grandfather was the MC. One night a few of the dancers got the flu and my grandfather called a talent agency up in Boston for some fill-in showgirls. One of them would turn out to be my grandmother.

And so there are reasons these were the stories I heard the most. They are the origin story of the family. My mom and her three sisters loved to hear about their mom and dad falling in love. The stories were glamorous and dramatic. “Dad and the Studebaker” and “Mom’s Broken Finger” are solid. But the club stories were things like “The Day the Bear Got Loose,” “Dad’s Three Girlfriends,” “The Russian [forgive me] Midgets Get Stuck in the Snow,” “The Night the Great Dane Danced with the Stickup Man,” “The Night My Grandmother Climbed Up the Ladder Where My Grandfather Stood Hanging the Star on the Christmas Tree by the Coat Check and Surprised Him with Their First Kiss.” And “The Day They Piled into the Back Seat of a Friend’s Car on the Way Back from the Beach and She Sat on My Grandfather’s Lap and He Held Her Hand and She Had Never Noticed Her Hand Was So Small Before and She Knew That She Loved Him.”

I heard that story a hundred times. The last time my grandmother told it to me was the night my grandfather lay dying in an adjustable bed at Rhode Island Hospital. Her hand was in mine. It was so small.

Not long after, I moved in.

The house of stories was also a house of stuff. Eighty-something years of stuff. In closets and crawl spaces and crumbling cardboard boxes stacked in locked rooms. The cigarette cases and tiepins and Bakelite clocks and the roller skate keys—all of it.

My mom and her sisters, no longer needing to ask their parents’ permission to poke around in the basement, would send me on missions. One of them would call me up and say things like “There’s this big Coke sign, I think, from when Uncle Leo ran that concessions stand in Narragansett in the fifties. It would look amazing over my new stove.” And I’d go digging.

There was one artifact they all wanted more than any other. The holy grail of family ephemera was a record. The Baghdad had a record-pressing machine. It was a bread-box-sized device into which you plugged a microphone, and it would record whatever it heard by carving it into an acetate disk. There was a promotion at the club where you could pay a buck and then sing with the band and take your record home, like karaoke for keeps. Somewhere in the house, they all swore, was a recording of the floor show at the Baghdad. If I could find it, they could hear the Club Baghdad. Could hear Dad sing. Hear him banter. Hear him introduce the showgirls. Picture their mother high-kicking in the center of the line. I just had to keep digging.

I lived in the house for seven years. Every now and then, the sisters would check in and ask about the record. I’d tell them about other stuff I’d found. Wonderful things from that golden era of the nightclub. Pictures of the chorus girls, of the dance floor, of the bear, before he got loose. Old menus: thirty-five cents for a boiler- maker, a buck ten for the Clams Casino. But no record. They’d be disappointed, but I didn’t care. Because I found letters. And diary entries. And pictures of my nana’s cousin Amy, the flapper, who she’d once told me had opened her world up and made it seem possible to do things like become a showgirl and cool to try smoking weed in the back of a Lindy Hop hall with two of the Mills Brothers. Okay to climb up the ladder and make the first move. I found union cards. Streetcar transfers. The ID bracelet from the trip to the hospital when my grandparents had the baby who never came home. The stuff of lives. Of raising kids. Of doing the work to sustain a marriage for fifty years after a kiss in the red-green glow of a Christmas tree by the coat check. Of my grandfather, in the years after the nightclub, putting a family on his back while working decades of double shifts as a steam fitter. Putting pipes into buildings, building boilers, when he used to sing and tell jokes and juggle dates with showgirls. So his four daughters could go to college. So I could write this for you now.

From the book THE MEMORY PALACE: True Short Stories of the Past by Nate DiMeo. Copyright © 2024 by Nate DiMeo. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.