“Predictive policing” technology is showing up in communities across the country

Many law enforcement agencies use software that crunches crime statistics, 911 calls and other data to try to predict where crimes are likely to happen. The idea is, this can help them know where to deploy scarce resources.

A recent investigation by Gizmodo and The Markup looked into one of the companies doing this, PredPol, and found that the software disproportionately targeted certain neighborhoods.

Aaron Sankin is a reporter with The Markup and one of the authors. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

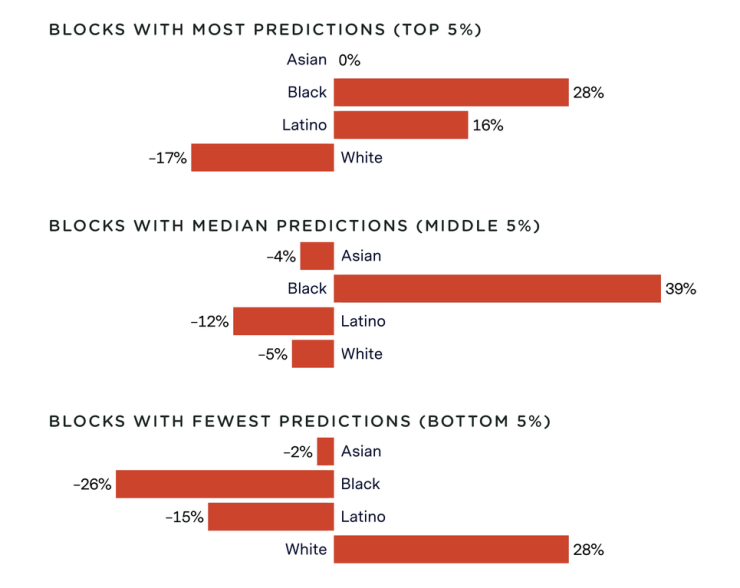

Aaron Sankin: This system tended to produce predictions that were clustering in areas where Black and Latino and low-income folks live, while not suggesting that same level of scrutiny be given to areas where more white people or middle- or higher-income people live.

Kimberly Adams: Which, one could argue, those are the communities that already tend to have an overrepresentation of police presence. What’s different about what’s happening with the software?

Sankin: Fundamentally, whether an officer is at a location because this is just their own kind of preconceived idea of where they should be, or department brass told them to go to this location or it was a computer program doing it — the ultimate effect is the same, is that there are going to be more police officers in a given area. And what that means is going to be different in each community. There are some communities where, I’m sure, people by and large want more police officers, and there are other communities, as we’ve seen from last year’s kind of wave of protests around the country, where people in these communities were not particularly happy with the level of police presence in their areas. And when police are in an area, they often will have interactions with the residents of that area. And those interactions can turn negative, and when those interactions turn negative, they can have negative consequences for people. There’s criminology research showing that if adolescent boys are stopped by police, then in the future, [they] report higher levels of psychological and emotional distress, and then go on to engage in more deviant behavior. Or even things like having lots of police stops in an area could then lead to people in that area, just being less likely to engage with the government at all — to do kind of basic civic services like report to 311 that there need to be potholes filled in their communities.

Adams: Well, it also ties into this conversation about algorithmic bias, because if that’s what’s feeding into the algorithm to determine where police should go, is this helping? Or is it reinforcing, maybe, preexisting biases?

Sankin: The idea behind a system like PredPol is that it’s supposed to take kind of the individual bias of a given police officer out of the equation. There are issues around how not every crime that occurs, and not every victimization that occurs, becomes a piece of a crime report or a piece of crime data that’s fed into the system. If a police officer is driving around a given area because they think there’s crime there, they’re more likely to see crime occurring, which then creates a crime report and generates more predictions than in areas where they wouldn’t otherwise be. So I think all of those things acting in tandem are creating a push in one direction to — if you’re just looking at this, this data that is even outside of an individual police officer’s set of biases could still replicate the same kind of patrol locations that they had before.

Adams: And that doesn’t even really take into account the crimes that occur out of public view, like domestic violence and many types of sexual assault.

Sankin: Yeah, and that was something that we found as well. In our data set, we were able to see what crimes are being predicted for, and that’s something that’s set by each individual police department. And we had seen a number of police departments predicting for crimes like sexual assault, and then when we brought this, and we reached out to PredPol and said, “Hey what’s, what’s going on here?” they said, “This is not something that we advise our clients to use to predict.” Because, as you said, like, these things aren’t, these are happening outside of public view, it’s not usually going to create, like, a large deterrent effect by sticking a police officer on, you know, down the block from where this is occurring. So I think to that point, like you, this is not exactly a blunt instrument that could be used for all types of crimes. And at the same time, we also found about four different departments using this to predict drug crimes, which is something that in previous public statements, PredPol’s leadership has said they do not advise their clients to do simply because there is a long history of racially biased enforcement of drug crimes. And PredPol’s leadership has said that they don’t want this happening. But we still found it happening at a handful of departments.

Adams: Can you give me a sense of how much software like this costs and the size of the industry overall, even beyond PredPol?

Sankin: So in terms of PredPol, kind of looking at public contracting data, we found it ranging from somewhere about like $10,000 for smaller departments up into like the low hundreds of thousands of dollars for larger departments. But I think predictive policing, as PredPol does, and other companies that kind of do this kind of specific place-based thing, they’re in a kind of larger subset of the police technology industry. And the idea of taking in data about where and when and to whom crimes occur, and then using that to kind of inform how police departments can be proactive, is not something I think that’s, that is going away anytime soon.

Adams: I noticed in your piece that in this data you pulled, you also found evidence that this software is being used for other kinds of monitoring as well, like a protest in Bahrain and oil theft, I think, were the examples that you had.

Sankin: Oh yes. We did find a couple sets of reports globally, in Venezuela and the, and Bahrain. We did not go and investigate those particularly deeply, simply because what, we were really trying to limit our analysis on law enforcement in the U.S. But that data is there. And we did, we did in fact find it. So that does suggest that this sort of technology is being used globally and in, potentially, in lots of different ways outside of just, you know, trying to prevent car break-ins in given cities across the U.S.

Adams: I can’t let you go without asking this question. So how close are we to the book and movie “Minority Report,” which is where people are getting arrested before they even commit the crime?

Sankin: Well, so there’s kind of two different parts of predictive policing, right? And fundamentally, they’re really like two pretty different technologies that have the same, that kind of grouped under the same name, which is what we were looking for, is we’re looking at it’s really place-based stuff. So it’s really just like, you set where they think crime might occur. But there is, you know, another set of predictive policing technologies that do look at the individual, that look at trying to find who is going to be the next victim of crime or to be perpetrating crime. And those technologies have been used by police departments, to, I think, very controversial and often fairly harmful uses. So, you know, I think it’s hard to say where we are in that — I think anyone would be advised to have a healthy degree of skepticism about how truly effective, you know, we can be in predicting basically anything. You know, as Yogi Berra said, “It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” And I think that’s true for, for humans as well as algorithms.

Related links: More insight from Kimberly Adams

We have a link to the full investigation. Heads up: It’s a long read but goes deep into how the team stumbled upon the trove of data that revealed these trends, and the methodology, including formulas the team used to measure the impact of the algorithms.

We also have a link to PredPol’s site, where the company says its software is being used to help protect 1 out of every 33 people in the U.S.

PredPol also says that by using a data-driven approach to deploying officers, communities are able to save money, increase transparency and potentially reduce crime.

And the company’s CEO, Brian MacDonald, pointed us to research showing crime tends to concentrate in specific areas and that helping police figure out where those areas are makes sense. In an email, he wrote:

“Numerous studies show that crime consistently tends to concentrate in narrow geographic locations. This is commonly known as ‘the law of crime concentration,’ first proposed by sociologist David Weisburd. You can read more about it here. Our patrol guidance is based on crimes reported by the victims themselves. We have no data on the underlying demographics or economics of any of the areas under patrol, and we never use any personally identifiable information. The only data we collect and use is crime type, crime location, and crime date and time. That’s it. This is the most objective data we know of. Given that the primary goal of police is the protection of people and property, it makes sense that their time is best spent in areas with higher crime rates. We help our agencies identify those hotspot locations.”

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.