Social media, elections and fake news: India edition

India holds its national elections next week. And as voters get ready to head to the polls, they’re being targeted with false and misleading information. The platform of choice? WhatsApp, the messaging service owned by Facebook that allows users to send encrypted messages to other individuals, groups of people and forward messages they’ve received.

According to a survey conducted by Microsoft, 64 percent of Indians reported they’ve encountered fake news. Marketplace tech host Tracey Samuelson caught up BBC producer Kinjal Pandya-Wagh to talk about the role of WhatsApp in India’s election. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kinjal Pandya-Wagh: I am myself a part of nearly 20 WhatsApp groups, including society WhatsApp groups, family WhatsApp groups, and all of that. And all of these groups are used to share information. They’re used to share pictures, also chat and exchange messages. It’s used for everything, largely to share news and information as well, and a lot of that does end up to be fake.

Tracey Samuelson: So give me an example. …

Pandya-Wagh: Yes. Fake news around politicians, fake news around what politicians have done, what they’ve said, how they laughed about things and how they cried about things.

Samuelson: How they laughed about things?

Pandya-Wagh: Yeah, I’ll give you a recent example. You know, in India and Pakistan, tensions were high recently after the attack in Pulwama. You know one politician’s picture [went] viral in India and it was shown that he is visiting the last rites of a soldier, and over there he’s laughing. And you know, it was obviously a doctored image but that was viral, and it was basically being spread to show that “Oh, look, this politician from this particular party was laughing about this. Is this really right? Or do you really think we should vote for him or this party?”

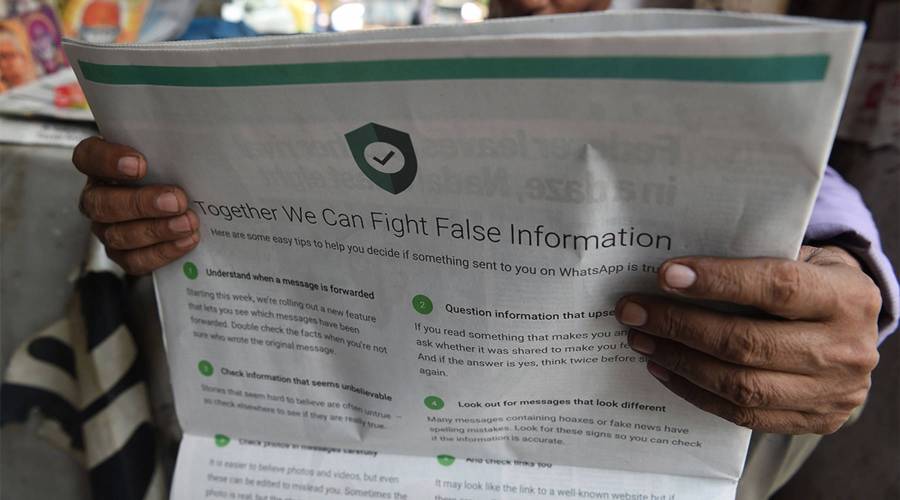

Samuelson: What is Facebook and WhatsApp doing to try and stop the spread of fake news?

Pandya-Wagh: Recently, Facebook has actually pulled out a lot of political pages from its platform, saying that these are the groups and accounts that are involved in inappropriate behavior. Now, it’s not very clear what they mean by that.

Samuelson: So they’ve blocked those accounts?

Pandya-Wagh: They have blocked those accounts. And WhatsApp has also started a helpline to verify fake news, basically, where people, Indians, who are using WhatsApp can share pictures, videos with WhatsApp, and ask whether these are authentic.

Sameulson: And is it working?

Pandya-Wagh: Well, it started. I mean, this announcement has just come a couple of days ago.

Samuelson: Messages on WhatsApp are encrypted, which actually makes this harder for governments and the company to trace or crack down on.

Pandya-Wagh: Yeah, absolutely. But this is also the unique selling proposition for WhatsApp, for its consumers and for its users. Because the users really want privacy, to their conversations with people, to their calls and to the kind of messages that they are exchanging. So if WhatsApp does agree to remove encryption, that basically means that they are compromising on the kind of privacy they are giving to its users, and then users might not be happy with WhatsApp. So this is really going to be a sticky point. The Indian government has been [pressuring] WhatsApp to make information more accessible to the government, to see who’s saying what and who’s doing what on WhatsApp. But I don’t think it’s going to be that easy for WhatsApp to agree to that, and for the government to get to do that, because both of them will be criticized

Samuelson: Do you think that the spread of fake news on WhatsApp could actually influence the Indian election?

Pandya-Wagh: I mean, obviously we cannot say that for sure. We have already seen in the last year how the kind of information that is shared on WhatsApp has an influence on people’s social behavior. Lynchings of people on the streets across India, after the spread of rumors of child kidnappers, has led to people being killed, innocent people being killed. So that is a good indicator that information that is shared widely on WhatsApp can influence people’s thoughts and people’s behavior.

Related links: more insight from Tracey Samuelson

That WhatsApp tip line Kinjal mentioned? It might not be the real-time feedback tool it initially appeared to be. Buzzfeed reported this week that it wasn’t getting timely responses to the texts and links it submitted to test the hotline. In response, Proto, an Indian start-upthat’s partnered with WhatsApp on the service, clarified that it’s actually a research project. It will primarily gather data and won’t be able to respond to every submission it receives. It shouldn’t be relied upon to combat political rumors in the run-up to India’s election.

Before India, there was Brazil. The Washington Post chronicled the spread of fake news on WhatsApp in Brazil’s presidential elections last fall.

And last month, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg came out with a long piece about the future of social media. He thinks it’ll revolve around private interactions, similar to those happening on WhatsApp, a “digital living room” to compliment Facebook’s digital public square. If he’s right, he admitted, the switch to private communications would make it even harder for companies to spot and stop fake news.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.