What the authoritarian crackdown on social media means for global activism

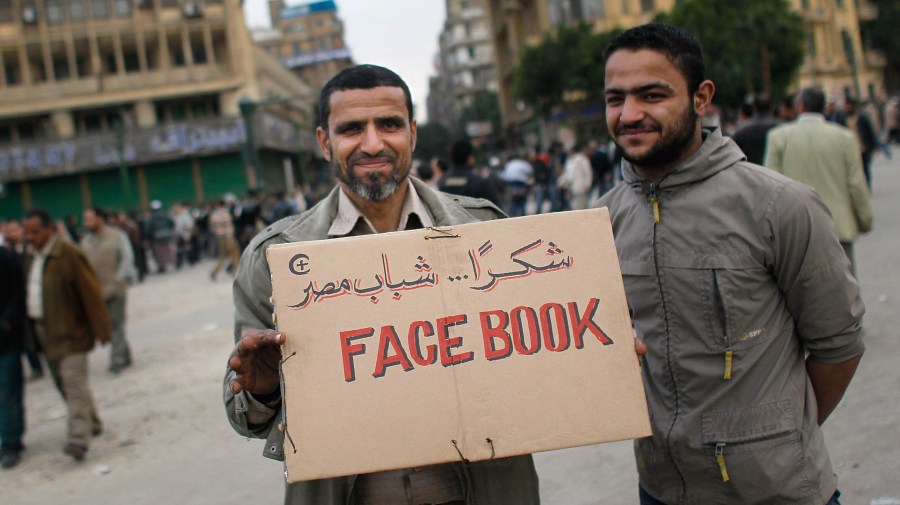

It’s been more than a decade since the revolution that came to be known as the Arab Spring, when protesters across the Middle East challenged — and in some cases overthrew — authoritarian governments. Social media played a central role in helping activists organize and build support.

Now, autocratic leaders around the world have been stifling dissent on these platforms or banning them altogether. Russia, China, India and Nigeria are some recent examples. Could social media play the same role today that it did in 2010?

Philip Howard is a professor of sociology, information and international affairs at Oxford University. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Philip Howard: When the Arab Spring happened, the newness of social media platforms, the newness of Twitter and Facebook, really gave those tools an edge for activists. Dictators weren’t there. The police weren’t on social media as much. It was mostly a tool for young people, and those revolutions were perhaps unusual in that they were led by young people, and they were sparked off in Tunisia, and in Egypt, by stories, photos, videos of young people being beaten up. These things went viral at a time when state agencies didn’t have a response strategy, so the fact that they were new was quite important.

Amy Scott: And now, a decade later, governments have figured this out.

Howard: Definitely. Governments employ hundreds, if not thousands, of people to monitor social media. They have campaign teams and PR agencies that help maintain sort of an image on social media. They do much more active tracking of who’s saying what. In fact, several governments use social media as an intelligence tool to figure out who’s meeting who and who knows which opposition leaders are networking with each other. It’s very much a tool for social control as much as it is for social protests these days.

Scott: Facebook is in many of these countries basically the internet. It’s all there is, and I’m wondering what role the size plays in the ability of new platforms to provide an alternative.

Howard: Facebook is definitely the behemoth in all of this. They dominate the market for social media services. They buy up new platforms when those platforms become interesting, and I think it means that it’s very hard for a new social media platform to compete. I also think it means that smaller social media firms, like Twitter or Telegram, are waiting to see how Facebook responds in a lot of situations, so if Facebook decides to make a tough decision, make a tough call in an election, other social media firms often follow suit. But if Facebook decides to stay out of it, then other social media firms also won’t get involved. And Facebook’s very much in a leadership position in a lot of these decisions.

Scott: I’m also wondering how American social media platforms monitor political activity abroad and identify potential problems?

Howard: The largest of the social media firms, Facebook, has many teams. They tend to gear up when there’s an election. They’ll grow the staffing. They don’t cover all languages and they don’t cover all countries, and sometimes the teams are responsible for whole continents and subcontinents. So I think they are sort of understaffed when it comes to keeping track of the political sensitivities around the world.

Scott: Do you think they should be doing more? I mean, given how widely these tools are used all over the world, is this something they should invest more in?

Howard: Social media firms definitely should invest more on this. I think there’s two things they need to be doing. In each country, they need to be aware of the local sensitivities, the local context. That means learning the local language and having some capacity to deal with hate speech or racism or sexism that might happen in other languages. But then there’s a little bit of standardization I want to see. I think Facebook and Twitter have done some very creative things around election time in the U.S., around election time in Canada and Australia. But those “get out the vote” campaigns, the special apps and special services they roll out during elections in those countries, they don’t offer them to all countries. They don’t offer them in Ghana. They don’t offer them in Tunisia. And so, I think having a stable set of pro-democracy tools that are offered around the world is something I’d want to see from the social media firms.

We reached out to Facebook for more about how in operates in countries with authoritarian regimes. A Facebook spokesman said: “We always strive to preserve voice for the greatest number of people. This means we only restrict content that is illegal but doesn’t break our rules when we have a valid legal basis to do so and our international human rights commitments are met. We are transparent about content we restrict based on local law in our Transparency Report, and we are regularly assessed by an independent panel of experts on our commitments to a set of global principles on freedom of expression and privacy.”

Related Links: More insight from Amy Scott

One reason we called Phillip Howard? Back in 2011, he worked with a team at the University of Washington to analyze more than 3 million tweets, hours of YouTube videos and thousands of blog posts to study the role social media played in the Arab Spring. At the time, he said a cascade of messages about freedom and democracy across North Africa and the Middle East “helped raise expectations for the success of political uprising.”

You can read more about the crackdowns on social media in India and especially Nigeria, where Twitter recently took down a post by President Muhammadu Buhari for threatening violence. Buhari responded by indefinitely blocking Twitter in the country and ordering the arrest of any users of the app.

I mentioned earlier that in some places Facebook is the internet for a lot people. In many developing countries, the company’s Free Basics service offers bare-bones mobile internet access without data charges. Last year, the company expanded on that program with an app called Discover, which strips some content from websites, like photos and videos, to make them more accessible over cellular networks.

A new study from University of California, Irvine, and the University of the Philippines found that the service favored content from Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram. Those sites were more likely to be fully or mostly functional for Discover users than other sites. Facebook told tech journalism outfit Rest of World that the unequal treatment was unintentional and that the company has resolved the error. Critics have called the larger effort “digital colonialism” for serving up mostly Western content, primarily in English, without the tools of the open internet.

And, as Pride Month continues, the open internet advocacy group Fight for the Future is out with a report accusing Apple of enabling government censorship of LGBTQ+-friendly apps in repressive countries. The report says many of those apps aren’t available in 152 of its regional App Stores. Saudi Arabia, China and the United Arab Emirates top the list of countries with the most apps unavailable.

Apple told us it has blocked apps in a few cases where the company is following local laws, but that developers control where they make their apps available and often choose not to in certain locations for legal reasons or sometimes their own safety.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.