Chapter 4: The Battle of Newburgh

In 1961, the city manager of Newburgh, New York, declared war on its poorest residents by proclaiming, without evidence, that the city was overrun by welfare cheats.

“We challenge the right of chiselers and loafers to squat on the welfare rolls forever,” said City Manager Joseph Mitchell. He blamed generous welfare benefits for attracting new poor Black migrants to the small city.

In response, city officials launched a campaign of harsh crackdowns on welfare recipients that included surprise police interrogations, rigid eligibility restrictions and forcing able-bodied men to work to receive a welfare check. But were these new rules designed to reduce welfare fraud or target members of the city’s Black community?

After a national controversy erupted over Newburgh’s welfare rules, the city found itself at the center of a policy fight that’s still playing out today. It’s a moment in history when the belief that certain people need to be forced to work expanded its influence in our country’s system to help poor people.

Producer Peter Balonon-Rosen takes us back to Newburgh to retrace its war on welfare and examines how race became central to a battle over welfare policy.

Krissy Clark: Hey it’s Krissy you’re listening to The Uncertain Hour, we’re gonna pick back up right where last episode left off with producer Peter Balonon-Rosen and the story of an explosive battle over welfare in Newburgh, New York. A battle that would eventually influence welfare across America. Here’s Peter.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: On May 1 1961, Newburgh city officials tried a new tactic in weeding out welfare cheats. In the early morning in front of police headquarters. This line started to form first a few people, men some more, eventually a long line of new burgers, white and black, mostly women, many with infants in their arms, all with one thing in common. They were all there to get welfare checks.

Johanna Porr Yaun: Many have described it as a pitiful seen because the people who are on welfare obviously, many of them had, you know, reasons why they had their disabilities or they were elderly or or mothers with trying to wrangle children you know, and keep them in line as they’re waiting.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Johanna Porr Yaun the historian for Orange County where Newburgh is located, she took me to the spot.

Johanna Porr Yaun: At the time of the 1960s police the police station was in the basement here at City Hall.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: A building on a lively corner with red and green siding, some neatly trimmed bushes a few concrete steps. For years city officials had blamed welfare for attracting new poor people to town. People they claimed would rather get a government check than work.

Johanna Porr Yaun: For officials decided that as part of this idea of getting people to work, they needed to see the faces of the people that were on welfare and determine whether or not they were truly eligible.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Usually checks were mailed. But this month, city officials ordered people to pick them up here at the police station. People like these Newburgh residents from a 1962 NBC News documentary,

NBC Documentary (1962): What the welfare gives me and the kids. Every angle that I see that that I can make this money stress is exactly what I do.You’re trying to save pennies, which is completely impossible because you just can’t stretch the money that far.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: At the police station that day. Inside, there was a surprise interrogation waiting. Over the course of the day, police took 250 welfare recipients into a fingerprinting room and grilled them about their identity, their sex lives their drinking habits. And when they last worked, folks too ill or old to leave home, found police knocking on their doors the same questions. At the center of all this was new bricks new city manager Joseph Mitchell and ambitious chain smoking man who drove flashy cars and never shied away from getting into the headlines. The man who came up with the idea for this police interrogation, a woman came into the police station to congratulate the city manager. The local paper quoted her saying, “as a taxpayer I resent and I’ve long resented my tax money being used to support people who are capable of earning their own living.” But when reporters actually talked to welfare recipients. They often had been capable of earning their own living. They just needed help now.

News Footage: I paid taxes when I worked. Now I’m getting something back. I could figure it that way. But I don’t. I figure that people have been good to me. I was able to make a good living for myself. But through sickness more than anything else. We just had to lose everything.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: As the day wore on the line of the police station grew. But paper spoke to a white haired woman who had waited in line for an hour and a half. She was 71. This event the sneak attack police interrogation of welfare recipients in Newburgh, it has a name.

Johanna Porr Yaun: The muster. I mean, that’s what it was referred to.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Why the muster? That’s such a funky term.

Johanna Porr Yaun: Because this is a revolutionary war city. We speak like that here. I think

Peter Balonon-Rosen: The muster.

Johanna Porr Yaun: The muster. I mean, that’s what you do. When the mill, do you think of it as a military muster.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Which is technically a formal gathering of troops for inspection? And do they find any people who are fraudsters?

Johanna Porr Yaun: Nothing that I’ve seen reported.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: You’d think something as drastic as a surprise police interrogation of welfare recipients would mean like half of them were scamming the city. But no.

Johanna Porr Yaun: I don’t think that they were able to find anybody who was truly a Chiseler as they like to call people who were taking advantage of the system.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Chiseler that’s a term you hear over and over during this era.

Joseph Mitchell: We challenge the right of moral chiselers and loafers the squat on the relief rolls forever. We’re not looking for Chiseler as as the average person understands it. Mr. Mitchell portrays public welfare as an open cash register, into which 1000s of freeloaders chiselers, loafers and transients are free to dip their hands at the taxpayers’ expense.

Johanna Porr Yaun: The idea of a Chiseler is somebody who’s you know, chiseling, rather than working. It’s a term for some of these people that they believe we’re taking advantage of the system.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: I feel like it’s such an evocative term right, you can like see somebody kind of like cracking and carving away at this kind of big beautiful thing. At the city right carving away at the assets of the city or something like that. But yeah, it was it was a term that that Mitchell liked to use. Police grilled 336 people the day of the muster, they didn’t find a single Chiseler, didn’t find a single person getting welfare to evade work. Basically this muster, it was a buster, but to city manager Joseph Mitchell, the fact they couldn’t find anyone that was proof. Proof, it would take even harsher tactics to find welfare cheats.

Johanna Porr Yaun: Things really escalate. That’s when national attention turns to Newburgh.

INTRO

Krissy Clark: Welcome to The Uncertain Hour. I’m Krissy Clark. This season, we’re looking at the Welfare to Work industrial complex, the mandatory work that our cash welfare system is based on today, how for profit companies make money off that system, and the forces that are now pushing to bring work requirements to even more government benefits. Even if there’s not much evidence those requirements help people climb out of poverty. On today’s episode, we’re going back in time to look at one of America’s first Welfare to Work systems. And what that early attempt at putting work requirements into government benefits was designed to accomplish. It’s the story of one man in a small city that started to change the way some Americans think about welfare. One moment in history, when the expectation that certain people needed to be forced to work really began gaining momentum in our system to help poor people. We spent last episode looking at how a rumor that new black people were moving to Newburgh, New York to live on welfare riled up the city and how across the country suspicions grew about people getting welfare, right as the number of black people turning to it was growing. On today’s show, producer Peter ballin on Rosen brings us back to Newburgh and to the story of city manager Joseph Mitchell, a guy who wanted news reporters to pay attention to him and to write about his bold plan to crack down on welfare cheats. A plan that would ricochet across America and help shape the laws that people getting government aid still contend with today. Here’s Peter again.

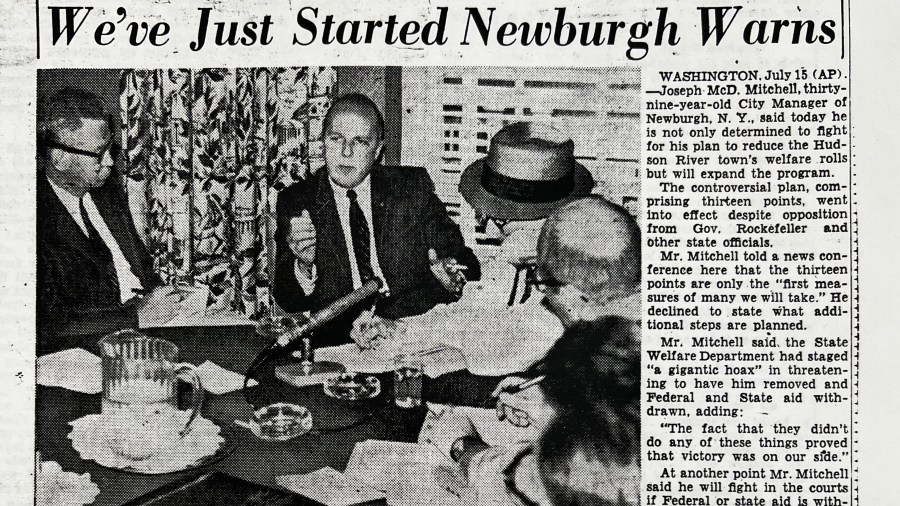

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Chapter 4: The Battle of Newburgh. After the muster city manager Joseph Mitchell had a dilemma on his hands. Newburghers came out on either side of whether a surprise police interrogation was a good way to crack down on welfare fraud, or plain harassment of the poor. State officials came to town to investigate whether Newburgh had broken laws. reports about everything became national news in the New York Times. Newburgh’s welfare crackdown made waves far outside of Newburgh, even if the muster itself was a flop. So the city found itself with two options ease up on their scrutiny of welfare, or doubled down.

News Footage: The city council of Newburgh gave Mr. Mitchell what he describes as extraordinary powers to take any action and welfare to reduce the costs and stop the influx of parasitic migrants into the city.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Despite not finding any Chiselers city manager Joseph Mitchell essentially declares war on welfare in Newburgh. At the time, the average cash payments to people who weren’t old, disabled or blind ranged from 25 to $32 a month. So up to about 300 bucks in today’s dollars, money for food, clothing transportation, welfare also covered rent and utilities. City Manager Joseph Mitchell he whips up this plan for people getting this money.

News Footage: City Manager Mitchell began a vigorous attack on the city’s public assistance program and together with the city council came up with a 13 point plan for getting tough with welfare.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: These 13 strict new welfare rules.

Johanna Porr Yaun: You hear this being called a 13 point plan.

Joseph Mitchell: Are there restrictions on welfare eligibility and payments.

Johanna Porr Yaun: Do you hear it being called the Mitchell plan?

Mary McTamaney: We know best we know who is a worthy human and who is not. And in 13 points we are going to determine your worthiness.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: A plan that would become a blueprint for other cities. 13 points in Newburgh took existing welfare rules from across the country and push them even further. Under the 13 points, the city could kick unmarried mothers off of welfare if they had more kids. The city could take children away from welfare recipients whose home lives were deemed unfit. And each year the city would cut off welfare to all welfare recipients after three months unless they were disabled or elderly. Mary McTamaney Newburgh’s official city historian says the 13 points came with all these moral judgments baked in. Out and about and the city city manager Joseph Mitchell maintained the key issue was employment. He believed welfare recipients had failed to earn their own living. So they needed to be made responsible for finding work because of what he called, quote-

Joseph Mitchell: The irresponsibility and godlessness of man.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: At a noisy community meeting about the 13 points city manager Joseph Mitchell set dressed in suit and thin black tie. He smirked as the crowd got riled up, a local pastor stood up.

Pastor: I wondered, sure if you would be kind enough to publish in the newspapers, perhaps even nationwide, the fact that you have not found any Chiselers. Because what disturbs me sir is an air of suspicion. And I just like to wander to be able to do this faster you’re getting back to this.

Joseph Mitchell: We feel that there are a lot of technically qualified people on the rolls who are not actually truly needy.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: So city manager Joseph Mitchell put this big idea into the 13 points, make welfare recipients work. Marry the city historian says in the 13 points, there’s this early example of welfare work requirements point to which an able-bodied men on relief of any kind.

Mary McTamaney: Are to be assigned to the chief of building maintenance for work assignments on a 40 hour workweek.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Man who collected cash payments for people in immediate need of housing, food or clothing. Now, in order to get that money, they’d have to work for the city like cleaning streets or clearing land. If they weren’t working already.

Mary McTamaney: We’re not going to really just boot them to the curb. We’re going to give them the chance to earn that money we give them.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Beyond that formal go do work for the city if you’re not working already requirements. Point three would cut off welfare if someone turned down a job offer. Point five would deny welfare to anyone who quit their last job rules and regulations that seem on their face designed to weed out lazy people make sure they’re working, which could make sense if you believe people only turn to welfare if their total lazy heads. But if you take a second and look at who was actually targeted by the proposed rules, Tamara Boussac the French scholar writing a book about Newburgh, she says you can connect everything in this code. Back to the rumor going around the city.

Tamara Boussac: That Newburgh has become a haven for welfare recipients for African Americans who would rather get public assistance than work.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: And that signs and bus stations and train stations in the South were telling people move to Newburgh to live for free on welfare. Newburgh’s demographics had changed rapidly in the 50s new black people were moving to Newburgh from the south on many white residents moved out to suburbs. In a decade, the black population nearly tripled. City leaders have looked around and blamed welfare. Tamara says they used the 13 points to target the city’s new black population.

Tamara Boussac: With the idea that if you force these people to work, it’s going to rehabilitate them in a way it’s going to make them more fit for life.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: And we see this interesting thing happen. Unlike places in the south, which at the time explicitly had laws about where black people could sit and drink and go to school. Newberg wasn’t as blatant they took a different approach. But how do you say black people in city policy without saying black people? You find a synonym, obviously, Johanna says that’s where point eight of 13 comes in. It said newcomers to Newburgh could only get welfare if they had proof a job offer originally brought them to town.

Johanna Porr Yaun: When you talk about a newcomer who are you really talking about? It’s the it’s not new faces. It’s New Faces of black men and women and children.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: City Manager Joseph Mitchell didn’t mince his words.

Joseph Mitchell: We found that many of the folks that came in our city, they just had no plans. They were just vegetables in a sense.

Tamara Boussac: He said for example, and I quote, they are attempting to destroy us racially and statistically. It’s a very blunt, very straightforward racial accusation, you know that the white population in Newburgh is being replaced by this newly arrived African American population.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: But despite the rhetoric, when you look at the numbers in Newberg, it was not a place overrun by welfare recipients of any race. A surprisingly small number of people were actually getting any form of government assistance at all. The 900 or so people getting welfare which included many children made up 3% of the entire population in Newburgh actually just below the statewide average journalist sat down with city manager, Joseph Mitchell to push him on this rule that seemed targeted at the city’s new black population.

Journalist: Mr. Mitchell, do you feel that a person ought to be permitted to move freely from one state to another in search of job? Well, American customs, right certainly is but your your residency restrictions which required a actual job contract for applicants receiving relief?

Joseph Mitchell: Yes. So that’s nothing different than the US Immigration Service requires. You try and get into this country and see the red tape you’ll go through a gap that was fine.

Journalist: But I’m not talking about coming from another country.

Joseph Mitchell: The analogy is the same.

Journalist: Except that we’re all Americans here.

Joseph Mitchell: Right.

Journalist: And it is fine to say that you believe in it, but do you really, if you set up standards that rigid?

Joseph Mitchell: No let me put it this way. Migration, improvement, opportunity is the American way.

Journalist: Of course.

Joseph Mitchell: But not at the expense of the taxpayer.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: With these 13 points, Newburgh ignited a national conversation about how the welfare rolls might just be full of lazy freeloaders and something needed to be done. op eds and articles started appearing everywhere. Talking about Newburgh’s revolutionary work first welfare second plan. The New York Herald Tribune printed the entire 13 Point code on their front page down in Florida before it Lauderdale News wrote quote, we think it is in the great American tradition that all those who can do so work for their daily bread. Soon articles about the plan, some positive some not came out in papers in Chicago, North Carolina, San Francisco, Minneapolis. Johanna, the county historian says the 13 points were so popular literal fan mail came in.

Johanna Porr Yaun: 15,000 letters come in from the public.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: 15,000.

Johanna Porr Yaun: 15,000 letters in support of Mitchell’s plan.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Okay, that’s I mean, I guess it’s not like dollars where we have to say in 1960 15,000 is 15,000. That is a lot.

Johanna Porr Yaun: Yeah, there was there was widespread support.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Newburgh City Hall had to hire an extra secretary to deal with the letters. But not everyone was on board with the city manager and his 13 points. Critics in the press said, this seems pretty neat and stingy groups like the NAACP came out to say, this seems pretty racist. and state officials said yeah, this might also be pretty illegal. And what would happen next, would make those three points of pushback, pretty stingy, pretty racist, pretty illegal, really come to light. papers like the New York Times wrote editorials calling for 13 points, cruel and unusual punishment for the crime of being poor, a local labor leader compared city manager, Joseph Mitchell, to Detective Javert, the villain and Les Mis, who dedicated his life to tracking down a man who stole a loaf of bread. But Johanna says city manager Joseph Mitchell was like, his 13 points are really about this larger idea.

Johanna Porr Yaun: That you can’t be a fully functioning person in, in this world without having a deep work ethic. And he sees the welfare system as a blockade, you know, to that self development that’s necessary. So he spins this not just into something political, but also into something moral, and personal, that in order to be a whole person, you need to know the value of work.

Krissy Clark: But plenty of those people that city manager Joseph Mitchell insisted needed to know about the value of work. They knew how to work just fine already. And they decided to fight back against his new welfare rules. That’s after a break.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: When Newburgh’s 13 points became city policy, there was one group that heard the racial dog whistles that city manager Joseph Mitchell was blowing with his welfare plan, loud and clear to the local NAACP. But 13 points were clearly aimed at black people. One of Newburgh’s local NAACP leaders, the Reverend William D. Burton. He denounced the plan.

Ramona Burton: Denounced the welfare plan as a policy of containment to stop migrations from the south.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: This is Ramona Burton reading Reverend Burton’s words.

Ramona Burton: Reverend William D. Whit Burton is my father. I was considered his baby and I was very close with my father.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Ramona big smile lover of houseplants, says her father, Reverend Burton was a kind man who often gave sermons focused on civil rights. Sitting on her couch. She tells me he was the type of guy to keep his kids home from school on MLK Day, even before it was a national holiday. He was pastor at the region’s largest black Baptist Church.

Ramona Burton: Everywhere we went. I mean, it was always somebody speaking to him. I mean, our telephone for oh my gosh, our telephone always. I mean, it rang day and night.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Ramona was three years old when this welfare controversy happened. Her dad Reverend Burton, who had moved to Newburgh from North Carolina, he pushed back against the welfare plan. I had to read a quote from her father in a book about Newburgh’s war on welfare.

Ramona Burton: The city should realize that when a person is hungry, he migrates looking for food. He doesn’t have to have a job offer any places better than where he is. The people who come here, knwo nothing of the welfare system. They come looking for a job.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Ramona says people she grew up next to in Newburgh did not migrate to the city looking for welfare.

Ramona Burton: That doesn’t even make sense. People are just coming for opportunities. I don’t think people came here saying, Oh, I’m gonna go to Newburgh and, and become you know, subjugated to racism. So I can get welfare money. I mean, really?

Peter Balonon-Rosen: She says it’s one of those clear examples of when the government cracks down on black people and bars them from helper opportunities.

Ramona Burton: Then the system turns around and says, Yeah, but they did it to themselves.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: The National Black press note of how changes to welfare policy could be used to target a city’s black population. The New York Amsterdam News, one of the country’s largest and oldest black newspapers, denounced the 13 points as illegal black codes. So Reverend Burton and the NAACP, they started raising alarm bells, that these welfare rules supposedly all about work, were actually all about race.

Tamara Boussac: They write to the governor of New York, they write to, you know, the senators of New York and the representatives in the House of Representatives. And you know, saying be careful, this is what’s happening in Newburgh and this has to be stopped.

Johanna Porr Yaun: So our governor at the time in New York was Nelson Rockefeller, who is against the idea of implementing harsh rules on individuals who are in need.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Governor Nelson Rockefeller was not a fan of the 13 points.

Johanna Porr Yaun: The state is concerned with the legality of all of this.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Local state and federal governments chipped in for welfare costs. State officials said Yeah, yeah, might not be able to do these 13 points with our money without getting sign off from us. Federal official said any local welfare program that instituted work requirements, couldn’t use federal funding. In fact, more than half of the $983,000 Newburgh annually spent on welfare was fully reimbursed. City Manager Joseph Mitchell’s new rules put that funding at risk. Does that stop Mitchell?

Johanna Porr Yaun: No. In fact, I think the opposite it makes them say well, now we’ve got to make a stand.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: And on July 17th 1961, what’s happening in Newburgh is national news. It’s the first Monday of the 13 points take effect.

Johanna Porr Yaun: The reporters came out in droves to be present and see how the plan is implemented. The first thing that they do is they try to show that they’re putting people to work.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: And just like the muster that round up a welfare recipients at the police station, the ever flashy city manager Joseph Mitchell trump’s up a spectacle. This time he sends welfare officials scrambling to find groups of men to put to work in front of reporters. But when they go looking officials can only find three people who qualified for the work requirements that say unemployed able bodied men need to work on city projects. One man who on closer inspection is already working, just getting welfare to help make ends meet, so not subject to work requirements. Officials bring the other two men to city hall where they discover One man’s disabled so also not subject to work requirements. And the third and final guy is an iron worker with one eye who’s not working because his wife is in the hospital, and he needs to watch their five kids. city official send them both home. But despite this failure, this total inability to find chiselers, who could be working but we’re getting welfare instead. City Manager Joseph Mitchell turns to the reporters and claims victory. He declares without proof his publicity about the plan must have scared fraudsters off the rolls. And that’s why they couldn’t find anyone. Just like the muster. He comes up totally empty handed and just like the muster, he says it’s proof we’re on the right track. Mary, the city historian says to her, the 13 points had little effect on the welfare rolls.

Mary McTamaney: I think all his 13 points did was rile up lots of, you know, shallow, bad feeling.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: If you look at the numbers the years before and after the publicity over the 13 points, the average number of people getting welfare Newburgh fell by three people total. Not exactly boatloads of Chiselers frightened away. One month after that media fiasco first day, the New York Attorney General and the courts bar Newburgh from legally enforcing 12 of the 13 points, saying the city didn’t have authority to carry out these rules. The only point that was legally required welfare recipients to have monthly conferences about their case. And what are the reactions to that?

Johanna Porr Yaun: People are unhappy they feel that the state has overstepped their their role. So a lot of people locally who were on Mitchell’s side, are not ready to just quit at this point.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Johanna, the county historian says city manager Joseph Mitchell thought if the 13 points were illegal under existing law-

Johanna Porr Yaun: Those laws need to be changed.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: And actually, that’s exactly what happened. The Newburgh’s controversy caused so much national buzz you can find written correspondence from 1961 between President John F. Kennedy and other federal officials, I Newburgh for their own federal cash welfare reform, saying welfare become quote, an explosive issue. So they had to make sure their own reform focused on work. Under JFK’s welfare reform the next year, the federal government allowed local governments to institute work requirements in exchange for welfare. A move one congressional representative said was, quote, our recognition of the problem that became known nationwide as the Newburgh case.

News Footage: The Newburgh story has struck a responsive chord nationally.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Other cities across the country started eyeing Newberg for their own welfare reform. Nationwide polls from the time showed 84% of Americans specifically like to work requirements for welfare within the city manager Joseph Mitchell’s star kept rising.

News Footage: Today Newburgh city manager is a national figure carrying his war against welfare far beyond the tiny boundaries of his city.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: He traveled to Washington DC where conservative lawmakers embraced him. Papers like the Wall Street Journal continued to sing his praises. The city manager leaned into his status as a minor celebrity. He booked national speaking tours in roughly six months he made nearly 50 out of town speeches all over the country. He’d book appearances at colleges, political groups, and on talk shows where he’d rage against lazy people clogging up welfare rolls call for stricter welfare policies and beat the drum that Newberg like the rest of America needed more work requirements for people getting welfare.

Mary McTamaney: He was radical and radical people make good press.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Mary, the city historian says all that press gave Newburgh a national reputation.

Mary McTamaney: A big bully Newburgh kicking dirt in the face of a poor needy population. So I mean, it just made us look like mean bullies.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: But even as the city manager was out making a name for himself all over the country, trouble back home would do him in. Maybe it was the national spotlight that made them feel invincible. Maybe it was something else. In 1962. This guy with a reputation for cracking down on welfare Chiselers gets accused of some major chiseling himself.

Mary McTamaney: He is accused of taking a $20,000 bribe and that’s what drives him out of office, not welfare.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: So Mr. Anti-fraud gets caught up in front of his own?

Mary McTamaney: He gets caught up in charges of fraud. Yes.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: The city manager never got convicted, but it’s enough for him to read the writing on the wall to see a support Newburgh waning city manager Joseph Mitchell eventually resigned. As far as his claim that black newcomers were coming to Newburgh, just for welfare.

Joseph Mitchell: That’s false. Was false from the get-go.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Looking at the numbers, the year before the 13 point code was created, the city spent exactly $205 on relief for new people in town. And those 205 bucks in welfare dollars, at the very most could have covered nine people total for a single month, up to nine black migrants. That city manager Joseph Mitchell was so up in arms about.

Mary McTamaney: And it just became a hook.

Joseph Mitchell: After leaving Newburgh, his next move was to work for a white supremacist organization.

Mary McTamaney: I can’t get over the fact that he left us and went to the White Citizens Council. I mean, you wouldn’t make that move unless your mind was way over there. In a very, you know, racially divisive aspect.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Joseph Mitchell gets hired on as a field director for the Citizens Councils, aka the White Citizens Councils, a network of white supremacist organizations formed specifically to oppose school integration and stopped voter registration in the south.

News Footage: The Citizens Council forum, America’s number one public affairs program.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: He’d continue giving talk show appearances, like on this TV program specifically designed to drum up public opinion against integration.

News Footage: It’s a real pleasure to have as our guest on the program today, Mr. Joseph Miguel Mitchell, same here, Deaconess, nice seeing you again. Since your Newburgh experience brought you to national prominence know you’ve had a chance to talk with Americans in almost every part of our nation. Do you feel a majority of the nation is with us is what the principles of the Citizens Council is on this racial issue?

Joseph Mitchell: Oh, yes, no question about it. It’s a necessity to the preservation of our social order. There is a strong feelings about racial integrity. They know what is right.

News Footage: Joe, three years ago, back in 1961, you were the city manager of Newburgh, New York. And at that time, you received national attention and you proposed a revision of your town’s welfare policies. And now I believe that it’s fair to say that the action you started in Newberg has precipitated a new look at some of the welfare policies prevalent in this nation.

Joseph Mitchell: Oh, that’s right, Vic. Of course when the question came up in Newburgh, we had no idea that we take such a beating. But nevertheless, I think I’d do it. Again. Only a little better this time.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Talking to people in Newburgh about all this at times I got a feeling I was dredging up history. They didn’t want to go back to that the past was the past. Maybe it should stay that way. So as Johanna, the County Historian, what’s going on there?

Johanna Porr Yaun: I think this community was really wounded by this. This was a big wound to have the National Eye on Newburgh in such a negative light. So I think people don’t want to bring it up because they don’t want to. They don’t want to be defined by what happened here in 1961.

Peter Balonon-Rosen: Which I get, no one wants to be defined by the skeletons in their closet. But even though city manager Joseph Mitchell fell out of favor in Newburgh, certain welfare ideas he championed only grew nationally in the decades after.

Joseph Mitchell: We challenge the right of freeloaders, to make more on relief than when working. And when we challenge the right of people to quit jobs at will and go on relief like spoiled children.

Nixon: We need a program, which will provide incentives for people to get off of welfare and to get to work.

Reagan: It’s now common knowledge that our welfare system has itself become a poverty trap, a creator and reinforcer of dependence.

Bill Clinton: From now on our nation’s answer to this great social challenge will no longer be a never ending cycle of welfare. It will be the dignity, the power, and the ethic of work.

George Bush: I am proposing that every state be required within five years to have 70% of welfare recipients working work.

Obama: It’s a pretty simple concept.

Trump: It’s time for all Americans to get off of welfare and get back to work, you’re gonna love it.

Tommy Thompson: Get a job and stay off of welfare. And that’s what this whole reform program is all about in Wisconsin.

Krissy Clark: Next week, we head back to Wisconsin to see how politicians are still using welfare as a campaign issue today with the work requirements right on the ballot, and we go deep into exactly how for Profit welfare companies are making money off the modern Welfare to Work system.

Speaker: If you think about what’s been called welfare reform to point out, and the movement to add work requirements is a competency that no other company in the market has like Maximus.

Krissy Clark: Government is one of your customers businesses are another. What about the welfare recipients are they-

Speaker: I think of them more as the product of our company? There our inventory.

OUTRO

Krissy Clark: That’s next week in the next chapter of this season of The Uncertain Hour. This episode was written and reported by Peter Balonon-Rosen. It was produced by Grace Rubin, Peter Balonon-Rosen and me, Krissy Clark. Editing from Michael May and Catherine Winter. In researching this episode the book “The Despised Poor” by Joseph Ritz was crucial to our understanding of Newburgh’s 1961 war on welfare. So was the NBC white paper documentary “The Battle of Newburgh” – where much of the archival tape in this episode came from. Check both those out if you’d like to learn more. Research and production assistance from Marque Greene and Tiffany Bui. Betsy Towner Levine provided fact-check support. Scoring and sound design by Chris Julin. Jayk Cherry mixed our episode. Caitlin Esch is our Senior Producer. Bridget Bodnar is Director of Podcasts at Marketplace. Francesca Levy is the Executive Director of Digital. Neal Scarbrough is Marketplace’s VP and General Manager. Special thanks to Nancy Farghalli, Donna Tam, Curtis Gilbert, Reema Khrais and Camila Kerwin.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

This season of “The Uncertain Hour” tells the unheard stories of real people affected by the welfare-to-work industrial complex.

Stories like these are seldom in the limelight. It takes extensive time and resources to do this type of investigative journalism … to help you understand the complexity of our economy and to hold the powerful to account.

We need your support to keep doing impactful reporting like this.

Become a Marketplace Investor today and stand up for vital, independent journalism.