The crude reality of debt

There wasn’t a ton of career choices waiting for Kate Beaton when she returned from college to the Canadian coastal village where she grew up. And none of the jobs available in the economically depressed locale could satisfy her desire to become an artist.

But before she could pursue her dream, Beaton had to address one major obstacle: $40,000 of student loan debt. The overwhelming feeling that debt created was still fresh in Beaton’s mind when we spoke with her. “To me, that was an astronomical sum. I could not imagine paying that much off,” she said.

So Beaton turned to the desperate get-rich-quick plan that people from her town had followed for years: venturing west to Alberta province in search of work in the oil sands. Her whole life, she’d seen friends, family and neighbors do the same, “like a conveyor belt of bodies going to the oil sands to work,” as she described it to our host, Reema Khrais. Now Beaton was ready to join them. She had no idea what that would entail, but she knew the money was out there.

Beaton wasn’t prepared for the harsh conditions and the harsher realities of life in the oil camps. In this week’s episode, she discusses the experiences that led to her memoir and graphic novel, “Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands.”

If you liked this episode, share it with a friend. And to get even more Uncomfortable, subscribe to our newsletter. Each Friday you’ll get a note from Reema and some recs from the “This Is Uncomfortable” team. If you missed it, here’s the latest issue.

If you want to tell us what you thought about the episode or anything else, email us at uncomfortable@marketplace.org or fill out the form below.

This is Uncomfortable June 8, 2023 Transcript

Note: Marketplace podcasts are meant to be heard, with emphasis, tone and audio elements a transcript can’t capture. Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting it.

Reema Khrais

In October of 2005, Kate Beaton woke up at five in the morning, shuffled out of the one-bedroom she was sharing with two roommates, and made her way to the bus stop. It was the first day of her new job. She was wearing an old jacket, which barely held up against the cold.

Not normal cold. Really, really cold.

Kate Beaton: Like when you breathe in and it feels like there’s knives going in your throat, that’s, that’s the kind of cold. Or like if you breathe in, like into your nose and your nostrils just stick together.

Reema Khrais

In Northern Canada, where she’d just relocated, temperatures could drop to minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit, which I truly can’t even imagine.

Kate Beaton: it’s so cold that legally when it hits certain temperatures some of the workers are not allowed to work outside more than 15 minutes at a time that legally they have to come back inside and warm up

Reema Khrais

This was not your everyday 9 to 5. Kate was headed to work for a company called Syncrude… in the oil sands of Alberta —imagine a huge expanse of a black sticky, tar-like substance that can be processed into oil. It’s an isolated desolate place. Kate would be spending all day and sometimes, all night, in a frigid warehouse, handing tools to the workers out in the fields.

She was just 21. She’d be one of very few women, by some estimates, one woman for every fifty men.

This is not what Kate – or her parents – had envisioned for her. Going to college was supposed to spare her from this.

But Kate had taken out 40 thousand dollars in student loans. And if there was one thing she felt sure of, it was that her adult life could not begin with debt.

Kate Beaton: It felt like a foot on my neck it was just a pressure that wasn’t going to lift unless I was able to remove it.

Reema Khrais

Kate stood at the bus stop, stamping her feet against the cold with a few other oil workers beside her. The sun rises late in the winter when you’re that far north, so it was still dark out when they saw the headlights approaching.

She boarded and settled in for her first 40-minute commute.

Kate Beaton: And, uh, the first time that you see Syncrude coming out of the darkness, it is, it is just lights and smoke and flames and, uh, and you’ve never seen anything like it.

Reema Khrais

It felt like she had entered this bleak, alien world. Smokestacks…huge machinery…everywhere she looked she saw towering structures and flashing lights. Kate stared out the window, awestruck.

Kate Beaton: It’s an unbelievable site and you think we’re gonna go in there and, and this is where I work I, I just went and I hoped for the best sometimes you can be so naive.

Reema Khrais

I’m Reema Khrais and you’re listening to This Is Uncomfortable, a show from Marketplace about life and how money messes with it.

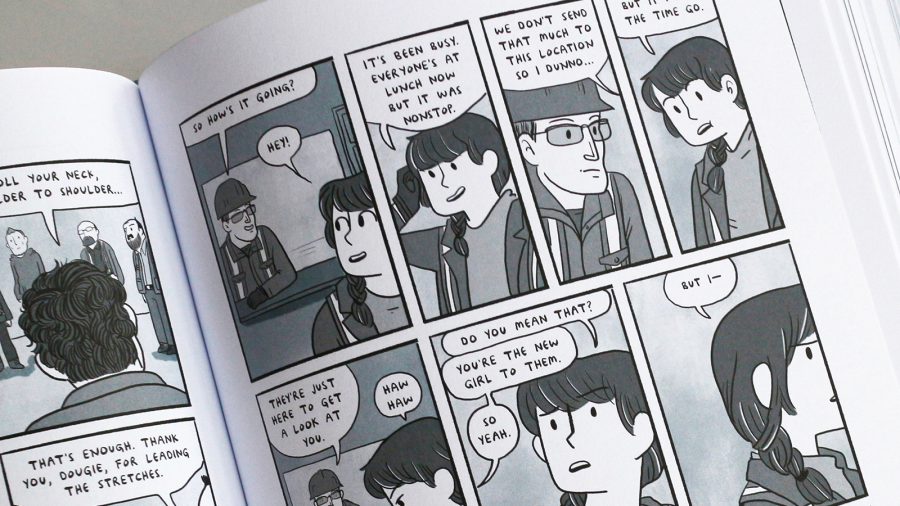

We learned about Kate through her graphic memoir, Ducks, which came out late last year. On the surface, it’s a story about the weight of student loans, and Kate’s determination to do anything to pay them off in one fell swoop.

But really, it’s much bigger than that.

This week, we follow Kate into a workplace that’s a world of its own, where boredom and loneliness are ever-present, a place where ordinary social expectations and rules don’t always apply.

It’s a story about class, home, and the forces that determine our fate.

And just as a warning, this episode contains descriptions of sexual assault.

Kate grew up in Cape Breton, an island off the eastern coast of Canada. It was a beautiful place to be as a kid—old forests, rocky cliffs, dramatic ocean views. The village where she grew up feels like what I imagine when someone says they grew up in a small place.

One volunteer fire department, a post office, a few stores and a population of 1500.

Kate’s dad was the meat manager at the local grocery store, and her mom worked at the credit union. They had four daughters to raise…and money anxiety was in the atmosphere of everything at home.

Kate Beaton: the fact that like this broke and it’s fixed with tape. or, or the state of, of the vehicles, which are, are always kind of sh you know, shabby

Reema Khrais

And it wasn’t just Kate’s family. Money was tight throughout the entire community . The main industries in town were fishing, mining and steel—industries that were dying, and leaving people financially ravaged.

As a kid, she couldn’t avoid hearing the nightly news reports…like the shutdown of the cod industry in 1992, which left 30,000 people out of work overnight. When the minister of fisheries ran up against the workers, there was this hugely publicized showdown…

Crosbie: I didn’t take the fish from the goddamn water.

Protester: You and your goddamn people took it! You and your people took it!

Reema Khrais

That same year, an explosion went off at a coal mine 2 hours away from Kate’s village.

Mine disaster news bite: At the time of the explosion there were 26 employees underground, working on the night shift.

Reema Khrais

Kate was 9 years old. One of the workers was from her village. She went to the service with her family.

Kate Beaton: I remember the adults saying no one’s gonna go to jail for this and no one ever did

Reema Khrais: And so what did you take away from that?

Kate Beaton: I knew my value as a worker, you know, the power of companies, when you hear stories like that, because those jobs, the people who took them knew that that was a dangerous place, but they were so grateful for a job. And that’s where I’m from.

Reema Khrais

As a teenager, Kate felt like the world was caving in, like there was just desperation all around her, and the only thing to do in Cape Breton was to leave.

Kate Beaton: You’d even go to the guidance counselor’s office and they would be like, leave And you’ll hear, oh, this person is gone. This person is gone. This person is going and you just felt like you were walking into this preordained thing.

Reema Khrais

And, really, there was nothing new about people leaving Cape Breton. The exodus has always been part of the island’s identity. But I was surprised to learn just how deep that goes.

Kate Beaton: There’s songs like, uh, heading for Halifax by Janelle and Cameron and, and, uh, the choruses. I’m heading for Halifax to see what’s to spare in the way of some work Song: Now I’m heading for Halifax, to see what’s to spare in the way of some work, and if there’s nothing there it’s Toronto, out west, to god only knows where, but there’s bound to be friends from back home…

Reema Khrais

Everything in Kate’s life was pointing outward, away from home. But everything beyond Cape Breton was like this big mystery.

Kate Beaton: I didn’t know anything outside the town you know how like when you’re playing a video game and the map isn’t filled in until you get there

Reema Khrais: Uh huh

Kate Beaton: It’s just like this big mist.

Reema Khrais

Her parents had never gone to college…but they wanted their kids to have better opportunities than they did.

For years, Kate thought she’d apply to animation school. She was that kid who drew all the time, sketching cartoons in her notebooks. She’d watch every animated movie she could find, pausing at the credits and writing down all the names, trying to figure out what the jobs were…what she had to do to become one of those people.

Kate Beaton: But then because I’m from this tiny place in the middle of nowhere, I also thought that there’s no way that I would be able to make it to animation school So I didn’t apply.

Reema Khrais

She talked herself out of it. She figured maybe she’d take some art electives…but that kind of work, it’s just a fantasy

Kate Beaton: That is one thing that coming from like a low-income place and a and a rural place will do to you. It will, it will take your confidence away. It’s kind of like I, that’s all I wanted my whole life. And then at the last minute I was just like, I can’t, what if I’m not good enough?

Reema Khrais

Kate ended up majoring in history and anthropology, at a small college 3 hours away. And like every other kid in town, she took out loans to pay for it.

The summer after graduation, she was living back at home, working an odd job. She had a 6-month grace period of interest relief on the loans. And it was around then that her parents started asking questions…

Kate Beaton: They’re like, where’s the job? You know, you’ve got the degree. Where’s the, where’s the job now?

Reema Khrais

With a degree, Kate could get one of the good jobs in town. She could be a nurse! A teacher! A job with benefits and a pension.

But there was this nagging voice in her head…what if she’d sold herself short on being an artist? She still loved to draw and make comics…maybe she could look into graduate programs, to really give her dream a shot. She broke it to her parents that…she didn’t really want one of those good jobs in town.

Kate Beaton: They’re like, what?! What were you doing? Why did you get the degree? Yeah. Yeah. That, that’s, that’s a bitter pill.

Reema Khrais

Kate wanted to give herself a chance at her dream of being an artist. But to do that, she wanted—needed—financial freedom. She needed to rid herself of debt, fast.

Kate Beaton: I needed to pay this off first for my own sanity because I just could not live with this If you’ve ever been poor and, like, and I don’t mean like broke, but like poor it is suffocating.

Reema Khrais

The most she had ever been paid was 11 bucks an hour for a summer job. Now, she owed 40 thousand dollars.

Kate Beaton: To me, like that was an astronomical sum. I could not, like, I could not imagine paying that much off.

Reema Khrais

Let alone at $11 per hour…at that rate, with interest, Kate would be paying off the loan for decades to come. She needed to make a lot of money.

Kate Beaton: And it just became very clear. It was, it was that I was gonna go to the oil sands.

Reema Khrais

Kate had seen recruiters pass through town before, recruiters from Syncrude, the oil company in Alberta. The whispers were everywhere…you could make lots of money working in the oil sands. They’ll hire you without any experience.

Kate Beaton: Everybody was going, and I mean, it was like a conveyor belt of bodies going to the oil sands to work.

Reema Khrais

For Kate, it was a simple decision. She wanted the freedom to make choices in her life.

Kate Beaton: I did not know how much money I would make. I didn’t know what kind of job I would get. I didn’t know anything.

Reema Khrais

All she knew was that the oil sands promised money.

At the airport, Kate’s mom wept. When would she see her daughter again? They hugged goodbye, and Kate boarded a plane that would take her 3000 miles west, to the frigid cold of her new home.

She found a one bedroom in town that she would split with two roommates. One slept in the room, one slept on the couch, and Kate threw down a mattress in the closet. She didn’t have much…but soon she landed a job at the oil company.

She had answered a newspaper ad for something called a “tool crib attendant.”

Kate Beaton: I went to an interview and I lied to them and said that my father owned a hardware store, so I knew a lot about tools.

Reema Khrais: Did you know anything about tools?

Kate Beaton: No, I didn’t know anything. And my dad is terrible with tools like he’s the one who’s going around the house fixing things with tape.

Reema Khrais

It would be Kate’s job to manage inventory—basically, she’d be checking out tools to workers who were running the equipment on site.

Her first day of work was a blur of orientation and safety videos. She was trying to get her bearings in this gigantic place…trying to not look too much like a newbie.

Kate Beaton: I wore like a blouse my first day because I was like, my first day of work, I better show up and literally everyone is wearing hoodies and like jeans.

Reema Khrais

Her new office was a big, freezing warehouse filled with all sorts of tools and equipment she’d never seen before. Safety gear, visors, drills, impact wrenches, impact wrench adaptors…

Everyday, she was out of bed at 5, at the bus stop at 6, ready to work by 7 for her 12-hour shift. Six days on, six days off…split between day and night shifts. There was a lot of repetition…

Kate Beaton: People coming to the counter, receiving pallets making orders taking orders talking to people seeing a lot of faces behind hard hats and glasses.

Reema Khrais

The tool crib became like a second home. At the beginning, the guys would help her out when she didn’t know what something was.

Kate Beaton: They all saw my job as cushy cuz it was inside, even if the inside was freezing.

Reema Khrais

The days blurred into each other. It seemed like no time had passed by the end of her second week, when her boss pulled her aside and handed her an envelope.

It was her first paycheck. She opened it right there.

Kate Beaton: I remember it being some like $1,200 and I was like, holy shit I was like, I am rich.

Reema Khrais

It was more money than she had ever held in her hands. More money than either of her parents had ever made in a single paycheck. She didn’t yet realize that she was getting paid terrible money by oil standards—about 18 bucks an hour…probably less than anyone there. But at that moment, it felt like a pot of gold. She paid her rent and made a payment towards her student loans.

The oil sands had promised money, and delivered. But it promised other things, too…and Kate was just beginning to understand what it’d mean to live in a place like this.

At first, it seemed mild enough…she’d get called pet names—Dollface, puddin’, ducky… Guys would comment on her big brown eyes. She got hit on a lot. She overheard guys talking about other women—the ones they liked…the ones they didn’t like.

But then, one night, something happened when Kate was alone in the tool crib…A man kept coming in over and over to see her.

Kate Beaton: He wanted to know if I had sex with anybody during my night shift, like for a little fun.

Reema Khrais: Oh woah

Kate Beaton: And, uh, and I said no. Um, and he got what he needed, but he kept coming back because it was cold. He said he was cold. And the warehouse was warm. And, um He was like, I’d like to fuck you on that pile of rags over there. There were like bundles of cleaning rags that we handed out to clean bitumen off the tools.

Reema Khrais

Kate was scared. She was completely alone…she didn’t know what to say.

Kate Beaton: After he left that time, I hid for the rest of the night if somebody came in kind of hid to the side unless I heard their voice and then I knew it wasn’t him. And then I would come and help them.

Reema Khrais

That night, she was supposed to wax the floor with this big buffing machine. There was an inspector coming in the next day to look through the warehouse. It was a gigantic floor. She was so spooked that she just didn’t do it.

Kate Beaton: And the next morning my boss was livid. He was insane I just remember his face being very bloated and, and angry.

Reema Khrais

She tried to think fast…said she’d been feeling sick the night before…

Kate Beaton: Of course, to him that just sounded like some bullshit, which it was and I hated myself and I hated him and I hated the man the night before. But I also felt so powerless because there was no one to call.

Reema Khrais

Kate nearly got fired that day. It had only been about two months since she arrived. But the harassment was like this smog in the air…

Kate Beaton: There wasn’t a day without it. It became part of the background noise. And there are gradients of it. There is anything from people being in your face saying things to you, touching you, getting too close it, it, it, it took all forms.

Reema Khrais

One time, guys lined up all the way around the tool crib to catch a glimpse of her, to rate her body out of 10…compare her to the other women on site. Other times it was dumb stuff…like the day she was sent to town to go get a cake for someone’s retirement party.

Kate Beaton: Then I was like, wait a minute What kind of cake does he like? And my coworker was like, “any kind you jump out of, Dollface!” and even now that’s so funny cause it’s so stupid.

Reema Khrais

It was strange…everyday, life could be offensive, funny, distasteful, scary…all at the same time. Dealing with the harassment began to feel like something she just had to endure, the price of admission to the life she really wanted.

As the months passed Kate just tried to keep her eye on the prize, still making her commute from the town to the site, day in and day out. She was making more money than she’d ever made. Still, she was realizing that after rent and utilities, 18 dollars an hour was hardly enough to make a dent in her loans.

She needed to ramp things up…to get more money, faster. And it was right around then that Kate was offered a job at the camps.

If the oil sands were like military basic training, the camps were the special forces.

Kate Beaton: You slept there with everybody else, so you never escaped it. And when I first arrived at the camps, I didn’t know what it was going to be at all.

Reema Khrais

The camps were a tradeoff: You didn’t have to pay rent…didn’t have to worry about groceries…no bills whatsoever. You could save nearly every dollar you made.

Kate Beaton: Even making, like, even making $18 an hour in the camp, it’s different when you, you pocket literally all of the money without anywhere to spend it. There’s nowhere to spend it when you’re on site.

Reema Khrais

The catch….is that you live in a long trailer with dozens of other guys, 24/7, out in the middle of nowhere.

Kate Beaton: people were cut off and isolated from anywhere.

Reema Khrais: Yeah.

Kate Beaton: It was a marked difference. And you saw what, what? Living conditions and working conditions did to people

The first night that I was there I slept with, uh, without locking my door And then I, I woke up in the morning and my door was wide open.

Reema Khrais: Oh God.

Kate Beaton: somebody had opened it and just left it open while I was sleeping

Reema Khrais: Do you remember what you felt that morning?

Kate Beaton: terror

Reema Khrais

Kate started locking her door after that. But the lock was mostly a comfort blanket…

Kate Beaton: You would wake up in the night and, and the doorknob would be, would be jiggling

Reema Khrais: Oof…

Kate Beaton: with somebody trying it. And, um, you’d think sometimes maybe they’re just mistaking where their room is It’s a long corridor with a bunch of doors. And look, they all look exactly the same. But then, then you’d talk to the other men that you work with, like, oh, it’s like my door not rattling. And they’re like, that doesn’t happen to me.

Reema Khrais

It was as though she’d entered another world with its own rules and logic. In isolation for weeks on end, the guys around her went stir crazy, jockeying for attention…throwing around big sums of money…almost no women, no family, nothing to do except work.

The way Kate saw it…these guys weren’t especially “bad”…they were just guys in a corrosive situation.

Kate Beaton: They’re honestly sometimes so bored that they’ll do insane things like this that make no sense and probably had no plan for after the doorknob worked. If, if that even makes sense to you. It makes sense to me.

Reema Khrais: No, it does. It does.

Kate Beaton: I don’t even think that those people wanted to come in and do anything. I think they were just trying the door just to try it because they’re so fucked up by being in this place that destroys your brain

Reema Khrais

A lot of her coworkers were from places like the place she was from—small, working class towns. They were sending money to their families back home.

They could make an offhand sexist joke one moment and then be sweet and genuine the next. There was the mechanic who secretly tried to teach her how to knit…the guy who gave her big, framed photographs of the Northern Lights…

Then there was the guy at Christmas. That first Christmas, Kate couldn’t afford a ticket home—it would have meant spending every dollar she had saved. Her mom sent her a plastic tree in the mail with little ornaments…but it felt too sad to set it up.

On Christmas Eve, Kate made her way to her usual post in the tool crib. It was snowing…everyone was unusually cheerful.

Kate Beaton: And they’re like making that overtime like, good for you. Like good for you girl. Making that overtime money

Reema Khrais

At some point during the night, this guy came in. Kate had seen him around— but they’d never really talked.

Kate Beaton: and he gave me a tin that had some cookies in it I was like, I don’t need these. And he was, and he was like, oh yes, take them, take them. My wife made them he said, I told her there was a young girl there, all, all alone by herself on Christmas evening. She said, that just won’t do. So she sent these to work with me today, these cookies.

Reema Khrais

Kate was taken aback. She didn’t know how to thank him.

Kate Beaton: That was such a nice gesture from this man that I really didn’t know. And this woman that I had never met, but she knew, they knew what it was like to be away from home on Christmas Eve.

Reema Khrais

As the man was walking out, Kate grabbed one of the ornaments her mom had sent and dashed outside to give it to him.

Still…the bad persisted along with the good. And Kate kept reminding herself of her north star. When I leave here, she thought, at least I’ll be free of my student debt. When I leave here, I can start focusing on my art.

Meanwhile, Kate started to notice herself changing. It’s like she was starting to get used to the harassment. Numb to it.

Like so many of her coworkers, she’d arrived at the oil sands as a sort of exile—casualties of poor opportunity at home. But once they got there, they became casualties of something else, isolation and grueling work. And sometimes, they lost themselves.

Kate Beaton: We also in so many ways have not equipped men with the tools to deal with pain I’m, I’m generalizing immensely here, but, but so many men are raised to, to just ingest their own pain and never speak it, never complain, just work and of course it comes out somewhere. It comes out somewhere awful It doesn’t excuse anybody’s behavior, but you can’t just say this place is full of monsters because it is a place that is created by corporations to exploit workers and it does its job.

Reema Khrais

After the break… Kate’s breaking point …

Kate was on track. Every month, she chipped away at the debt. There was a rhythm to the weeks that passed—eat, work, sleep, repeat…eat, work, sleep, repeat. It was all going to be worth it once she made that final payment.

But late in the spring of 2006, everything changed.

Kate Beaton: So the first time it happened, it was on site in the camp.

Reema Khrais

A coworker—one of the few other women there—had invited Kate to a birthday party where people were drinking.

Kate Beaton: The man who discovered that I couldn’t handle any drinks just led me to his room pretty much.

Reema Khrais

That night he assaulted her. The next morning, Kate was freaked out…confused.

Kate Beaton: I don’t accept what it is right away. I can’t talk about it. I’m sort of shell-shocked.

Reema Khrais

Did anybody know? Had the guy told anyone? For days afterwards, Kate was desperate to take a break from camp. She agreed to go to a party in town with some friends.

When she got there, someone handed her a drink.

Kate Beaton: I went to the bathroom and I dunno how long I was in there, but when I got out, everybody else was gone. it was just this one, one guy standing there I was crying when he did it and cuz he was like, don’t do that. And uh, cuz we have to hurry up before cuz we have to go meet the boys.

I think I was raped twice in a short amount of time because I suspect that when you are vulnerable there are people who can really sense it and, uh, like, you know, like blood in the water. And I was not okay.

Reema Khrais

Kate felt like she didn’t have anybody to turn to. She worried, Who would believe her? She had heard how the guys talked about the women who complained.

All of this had happened during a moment that was supposed to be celebratory: Kate had helped her sister and a friend get jobs at camp, and they’d be arriving soon. They had expenses to pay off too.

For weeks, Kate had been feeling excited to have loved ones nearby. Now, she just felt on edge…protective.

Kate Beaton: And I realized in a lot of ways after the assaults in how much I had become inured to the world around me and what I was bringing these girls into, you know, when they would be like, what’s it like? And I was like, oh, it’s pretty terrible. But, you know, you get used to it, how blithe I was being about how bad it really was because I had gotten too used to it.

Reema Khrais: yeah.

Kate Beaton: And here they were coming in cold

Reema Khrais

When they arrived, Kate noticed how the men leered at them. She tried to shield her sister and friend…to tell off the guys who would stare or make comments. But after what had happened to her, it’s like she was completely hollowed out.

Kate Beaton: But I wasn’t gonna leave. I wasn’t gonna leave them there. They had just arrived. You know? like I brought them there. Like I, I need to stay and, and be very protective of them in this world. But I, in the few months that after they first came I was unraveling a bit.

Reema Khrais

Kate was outside of herself…in a kind of suspended state.

Kate Beaton: Somebody came up to me once and he was like, are you okay? And I was like, what do you mean? And he was like, well, I, I found you walking around outside at 2:00 AM you were talking to yourself. And, and I was like, I don’t remember doing that.

Reema Khrais

She was keeping an eye out for the guys who’d raped her…what would happen if she ran into them? One day, when she was out running an errand, Kate saw one of the guys with a group of his friends. It was raining, and they were huddled next to a building. Kate made eye contact with him. It had been about a month since the assault.

Kate Beaton: Somebody looked up at me and then all of their heads turned towards me and then they all laughed and, um, started talking to each other again.

Reema Khrais

It was too much. Kate could barely hold a conversation…Her sister had taken notice.

Kate Beaton: She was like, I talk to you and you don’t answer. You’re like always staring at the wall you don’t acknowledge things your head is in a different land. Uh, like something is wrong. Something is wrong with you. And I dunno what it is

Reema Khrais

The moment of confession finally came one evening a couple months after it happened. Kate and her sister were sitting side by side on Kate’s bed in the camps.

Kate Beaton: At that point I was still sort of blaming myself. I was like, it’s my fault I let it happen. I didn’t even tell her about the two of them. I could only tell her about one

Reema Khrais

Kate decided it was time to leave the oil sands. She’d been there for a year, earning $18 an hour. The plan was to be there for at least another year to pay off her debt. But now, the toll was too steep.

Kate Beaton: I felt I really, really needed to leave because I was clearly not doing okay And that’s very bittersweet because it’s, it’s almost like, you know, that you’re going to go and waste your time somewhere because you still have to pay it off.

Reema Khrais: How much did you have left?

Kate Beaton: half.

Reema Khrais

20 thousand dollars, sitting between her and her dreams. On the one hand, leaving the camps was this huge relief. But how was she gonna pay off the other half of the debt?

Kate moved to Victoria and found a job at a museum. This time, she’d be earning just 13 dollars an hour…21 hours a week. It was a huge pay cut. At first, returning to normal society, where she wasn’t surrounded by crowds of men who lived and breathed their work—it felt jarring.

Kate Beaton: I felt like an alien person like I didn’t, uh, I didn’t know how to comport myself in a social setting when people were gathering around and laughing with a drink in their hand. And I would just be so awkward.

Reema Khrais

Still, it was exciting. Kate went to the opera…hung out with hippie types…and for the first time in a long time, she started to draw again. She made a website for her comics.

Inevitably, though, she started to feel the financial squeeze. Kate had to get odd gigs to supplement the museum job. But that wasn’t enough, either.

Kate Beaton: I couldn’t have worked that hard and gone through all of that just to start piling up interest on the loan to get it back up to the point where it was just as much as it was before that, that seemed to defeat the purpose of the whole thing.

Reema Khrais

Kate was desperate. So one day, she decided to try a hail mary. She was sitting in an office in the museum that overlooked a beautiful harbor and historic buildings. The sun was shining down, it felt like a physical symbol of her newfound cultured life. Kate picked up the phone, dialed the 888 number for the loan office, and began to plead for mercy.

Kate Beaton: I was like well listen, I just spent a year like with this job where I was putting so much money on and I just needed a break from it cuz it was really hard So if, if I can have interest relief for a few months, Then I can work on my career a little bit and um, and then maybe go back to paying my student loans when I get ahead a little bit. And they were like, no bitch. [duck laughter]

Reema Khrais

Yea, no they were not gonna do that. The officer told Kate….there was no getting out of the interest charge.

Kate Beaton: And they were like, no Um, but what happened to that other job that you had that was paying so good

I was dressed in like, like an argyle sweater vest with a little cravat and like a skirt with knee socks and stuff like I, I wanted to look like a little museum lady And then I was just, you know, just picturing myself in like, in my work boots and stuff again. And I was just like, oh God. Like I, I, uh, I, I was, I was this whole other person, but I, I had to go back and beat that other person again.

Reema Khrais

Kate went home to her apartment, collapsed onto the couch and cried. It had been a year since she’d left the oil sands. A year of distance between herself and the assaults. She didn’t want to go back. But there was just no other job that could compete with the money she could make up there.

Kate Beaton: I needed to get rid of it. So I went back.

Reema Khrais

If Kate was going back to the oil sands, things would have to be different. She applied for a better position, in a different location, away from the men who’d raped her—and instead of the tool crib, she’d have an office job. She wouldn’t be in contact with the workers as much…no more night shifts. And her pay would jump significantly—25/hour.

But the safety came with guilt.

Kate Beaton: This move was like sort of stepping over the heads of people who in a lot of ways were more qualified, but I was more qualified on paper and I knew how to work Excel and, and that that’s the kind of thing that gets you ahead, is knowing how to work excel.

Reema Khrais

It was like her jump in station had exposed this tension between Kate and her old coworkers. On the one hand, they were cut from the same cloth. They’d ended up in the oil sands because that was just where their people went for work.

But on the other hand, unlike many of her coworkers, Kate had a college degree. And, for the first time since graduation, that degree was working its magic.

Kate Beaton: I got to work in the office. I got to get to have the nicer room. I got to sit on my ass all day in, in the office chair as they like to point out to me all the time. And they were kind of bitter about it, but I don’t blame them for that.

Reema Khrais

These guys, they had experience with tools and machinery that Kate couldn’t compete with. But just like that, she’d leapfrogged them. They had families at home…wives and little kids who depended on them. Kate was young and child-free.

Kate Beaton: Often people would bring it up to me, you know, you could walk away anytime you don’t like it here, you can just walk away. And you knew they couldn’t.

Reema Khrais: Because they needed to provide for their families or they felt like this was the only option.

Kate Beaton: Yes. In some cases it really was.

Reema Khrais

For months, Kate kept her head down. She’d work and draw…work and draw…she was posting stuff on her comics website, using the office scanner to upload images. She was starting to build an online following…amazed that people seemed to like her work.

Then on June 6th, 2008, Kate sat down at her desk to take stock of where she was with the loan payments. She did some calculating, paused, and then stared at her computer screen…

Kate Beaton: I was like, oh, I have enough to pay it all off

I logged into like my Royal Bank account and looked at my balance and just put the money onto it, the same amount that was owing. I put that exact amount in and, uh, and had like almost nothing left in my savings.

Um, and I was like, wow, it’s done.

Reema Khrais

She didn’t know what to do. She was just sitting in her chair in front of the laptop, alone…

Kate Beaton: so I was looking at my laptop and looking at that amount, and the figures matched and I, you know, I I was like, I, I did it. This is what I came here for and I did it. BUT UH when you, when you labor at something for like, um, for years and years, and then you get it, you’re, it is kind of anti-climactic.

Reema Khrais

It was weird. The promise that she’d made to herself—that she’d pursue being an artist as long as she paid off the debt— was suddenly sitting right in front of her.

Kate called her mom.

Kate Beaton: I said, mom, I have no money. And she went, what? I said, I have no money because I, I gave it all to the government. I I paid off all my student loans. I’ve paid them all off. I did it. And, uh, and she, you know, she’s like, oh, Katie she wanted to know what I was gonna do next. And so I’m gonna stay, stay here for a little longer and, and save up a bit more money. And, um, I’m gonna try and make it as a cartoonist. And mom was like, oh, Katie

Reema Khrais

A few months later, Kate left the oil sands for good. She devoted every spare moment to cultivating her web comic. And to make a long story short, she now makes a living as a full-time cartoonist. Her work has won several awards, and one of her picture books was adapted into a TV show.

She still worries all the time about money—she suspects that worry will never fully go away. But she’s been debt free since 2008.

Kate Beaton: Lots of people live with their student loans. But I, I needed to, I needed to pay it off in order to prove something to myself in order to, to move on myself. And in order to maybe justify some things that happened to me that like I went through this for this end. I needed to, I need to get rid of this thing.

Reema Khrais

Kate gets asked a lot whether it was worth it—but it’s a question she feels like she can’t answer. This is the only life she’s lived. She doesn’t know any other experience.

Kate Beaton: I can only say that without having gone to the oil sands, I, I wouldn’t be able to live the life I live now as a cartoonist living at home I probably would’ve taken a safe route, a safe job somewhere that that would’ve, would’ve supplied both rental pay and student loan pay. And I probably would’ve found myself stuck somewhere And so I, I benefited from my time there immensely, and I suffered from my time there as well.

Reema Khrais

A few years ago, Kate moved back home, to Cape Breton. It was a rare reversal of the standard exodus…the population is still declining. But now that she makes a living as a full-time artist, Kate can afford to be back there. She and her husband are raising their two kids just minutes from the street where she grew up.

When I asked Kate why she moved back, she said it’s because when she’s home she feels like she’s a part of the painting instead of something on top of it that doesn’t belong in the picture.

Kate feels tied not to just the physical place, but to the story of her home, a story that both pulls you in and pushes you out, where you feel deep love for the smell of the ocean and the quiet of the night, but also fear that opportunity here is not enough, where the songs remind you that this home is just temporary.

Kate has often described leaving Cape Breton as something preordained…but maybe her return was fated, too… as inevitable as the island’s ocean tides.

Alright that’s all for our show this week…

If you want to learn more about Kate’s story, and life in the oil sands in general, go check out Ducks, her graphic memoir.

If you have any thoughts about this story, or just wanna shoot us a note, you can always email me and the team at uncomfortable@marketplace.org, we love hearing from you all

Also don’t forget to sign up for our weekly newsletter if you haven’t already. There’s always great recommendations in there for things to cook or listen to or watch. You can sign up for that at marketplace.org slash comfort.

Camila Kerwin

This episode was lead-produced and written by me, Camila Kerwin, and hosted by Reema Khrais.

The episode got additional support from Alice Wilder, Hannah Harris Green, and Peter Balonon-Rosen.

Zoë Saunders is our senior producer.

Our editor is Jasmine Romero

Marque Greene is our digital producer, with help from Tony Wagner

Our intern is Yvonne Marquez

Sound design and audio engineering by Drew Jostad.

Bridget Bodnar is the Marketplace’s Director of Podcasts

Francesca Levy is the Executive Director of Digital.

And our theme music is by Wonderly.

Reema Khrais

I should also say that this is our intern Yvonne’s last week with us. For the last six months she’s helped us produce this new season for you all, she’s been absolutely wonderful and we’re really gonna miss her.

Alright, I’ll catch y’all next week.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

We know that as a fan of “This Is Uncomfortable,” you’re no stranger to money and how life messes with it — and 2023 isn’t any different.

As part of a nonprofit news organization, we count on listeners like you to make sure that these and other important conversations are heard.