Private equity explained

Here are two words we’ve been seeing a lot in the headlines recently: private equity.

Private equity, or PE (as it likes to be known in the trade), doesn’t like being in the headlines. It’s been there before, back in the ’80s, and it didn’t enjoy the experience. The press wasn’t exactly flattering. In fact the press was so bad that PE changed its name. PE used to be called leveraged buyout, or LBO — but the LBO became tainted goods, and a makeover was required. More about that later.

Right now, PE’s in the news because of Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, who used to work at a private equity company called Bain Capital, back in the ’80s. That was back in the LBO days, when LBO shops were accused of being corporate raiders and asset strippers. Remember Gordon Gekko in the movie “Wall Street?” He was a private equity guy. And that “greed is good” speech? That’s the private equity hymn.

So what is private equity, actually? Well, if public equity means shares in public companies — like GE and Google — then private equity means shares in private companies, like my uncle’s ice cream company. Or Facebook. Right?

Yes, but that’s not the whole story. When people talk about “private equity,” they’re usually referring to private equity funds, like Bain Capital or the Carlyle Group, rather than the shares those firms buy. You see, there are plenty of institutions that buy shares in private companies. Venture capital funds, for one. And hedge funds. What distinguishes private equity funds, is that they buy these shares in a particular way. In fact they buy entire companies using that technique I mentioned earlier — the infamous leveraged buyout.

An LBO looks pretty simple on the face of it. It’s really just the way a bunch of people get together and flip a company for a profit.

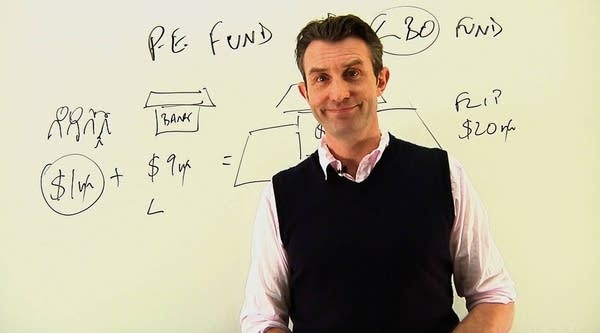

It’s rather like an episode of “Flip This House,” where a family clubs together to renovate a mansion in Malibu. Each member of the family chips in 100K each, so they have a down payment of a million bucks. Now they go to the bank and borrow $9 million. They buy the manse, sell off half the land around it, knock down the servants’ quarters and sack everyone but the butler. Then they put in wooden floors, granite countertops and a steel fridge and two years later, they sell the place for $20 mil. The bank gets its money back, and the family divides the $10 million or so that’s left. (They had to make interest payments on the debt, remember!)

Private equity funds do the same thing with companies. They get a bunch of investors together to pony up some cash — that’s the equity; then they go to the bank and borrow several times that initial amount — that’s the leverage; and then they acquire a target company — that’s the buyout. They then tweak the company with the aim of making it more profitable, so that they can sell it off in a few years for a profit. Pay back the loan and split the profits. It’s a bit like management consultancy on steroids.

And it’s not an other-worldly business. If you have a pension or a retirement account, your money is likely invested in LBO activity in one of two ways. Either your pension fund is an investor in the PE fund itself — and plenty are — or your pension fund has bought a slice of that bank debt. You think the bank holds that whole loan? No way. It slices the loan into little bits and sells it off to a range of other lenders from other banks to the Los Altos fire and police fund. That’s called syndication, if you’re interested.

Do private equity firms sack people? Yes, they do. My mum got the boot after 10 years working at a company that was acquired by Clayton Dubilier & Rice back in the ’90s.

Do PE firms create jobs? Yes, they do… if the company becomes profitable, grows and hires more people. That’s what happened in the case of Clear Channel, HCA and the most storied LBO of all, RJR Nabisco.

But sometimes things don’t work out the way PE funds hope, and sometimes PE funds make mistakes. When that happens, everyone loses — the workers, the bankers, the PE funds, and the institutions that invest your retirement money in them. Which menas you lose, too.

But I guess that’s capitalism, baby.