IMF’s acting director on U.S. and China: “It takes two to tango”

“Both sides should sit down and talk more,” says David Lipton of the International Monetary Fund.

The International Monetary Fund’s Acting Managing Director David Lipton is calling for more dialogue between the United States and China. Lipton assumed the role after Christine Lagarde resigned from her position at the IMF last month. Lipton spoke with Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal about escalating trade tensions, the fragility of the global economy and the state of multilateralism 75 years after the creation of the IMF. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: So I’ll tell you what, I saw you on CNBC the other day and here’s what you said. You said it’s time for countries to have dialogue, to reach agreements, to find a way through this since the global economy is fragile. How are we doing with finding our way through this?

David Lipton: I think we have some more work to do with new tariffs announced recently. It’s really important to keep the global economy growing, because if we have a recession, we probably have less ammunition for dealing with recession than we did at the time of the global financial crisis. We’ve used monetary policy space, central banks have lowered interest rates in many cases very, very low and fiscal policy has been used, debt levels have increased. So it’s important first and foremost that we do no harm that we not throw the global economy into recession. Now that said, on trade, both sides have to take this seriously and try and find a way through through dialogue.

Ryssdal: Well, so look — sorry to interrupt. I hear you on that, but it’s important that we point out that this is not just a China-U.S. thing, right? I mean, you’ve got Japan and South Korea going at each other, you got Brexit, and who knows what’s happening there. I mean, it’s a global trend.

Lipton: Yeah. I mean Brexit is another matter. I think though the basic message is this: This is a time to do no harm. Now on trade, you’re right that there are many different complaints about trade. I mean, there’s discontent about disruption from trade and from technology. It’s leading those who are losers to be upset. It’s leading to changes in political attitudes towards important matters like the integration of countries into the global economy. We’re seeing trade growth now slow to the point where in the first half of this year, trade exports actually fell on a global basis. So the key point is that everyone needs to be open to making changes to help remedy the problems and to try to deal with these discontents. That should be done openly. It should be done in a cooperative way, and that should include rethinking the international rules and the rules of the [World Trade Organization] if those are proving not to be satisfactory for the membership.

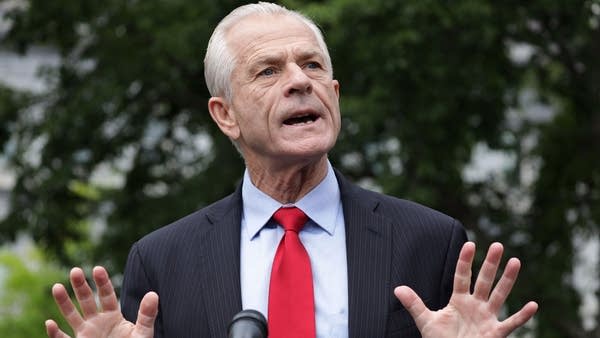

Ryssdal: All right, so let me get you back to the elephant in the room. You’re, like, around the corner from the White House and down the block, and I’m sure you can get [White House economic adviser] Larry Kudlow on the phone, you know, with a snap of the fingers. Do you believe the president of the United States and his trade advisers, Mr. [Peter] Navarro, Mr. Kudlow and Treasury Secretary [Steven] Mnuchin and Trade Representative [Robert] Lighthizer, do you believe they get that?

Lipton: I think so. I mean —

Ryssdal: Do you think or do you hope?

Lipton: Well, Secretary Mnuchin says that the United States would like to see free trade, free and reciprocal trade in a setting where there’s no tariffs, and their difference of approach is to use tariffs to try to get to that better outcome. You know, we take him at his word. The issue is that so far, the two sides haven’t been able to, through dialogue, reach some ways to improve international trade practices. I think China also has to consider that many of the practices that they’ve followed that really weren’t very consequential, say, in the year 2000, about when they joined the WTO, it didn’t matter for the world when China was a trillion-dollar economy, but now there are huge spillovers from Chinese approaches and policies now that they’re a $13 trillion economy. It takes two to tango. Both sides should sit down and talk more.

Ryssdal: Let me be clear on that and try to nail you down a little bit, please. President Trump gets a lot of the slings and arrows of this trade war. China has some work to do structurally and both internationally to get this done. Do you agree?

Lipton: I do, and I think, you know, we’ve been advising China on how to open up its economy, how to rebalance it years ago when it was an economy that was saving so much that it had a huge excess of exports over imports, the so-called current account surplus. I think they’ve made a lot of progress, but there’s surely enough left to do in the area you mentioned in structural reform, in opening up. There are still things that would be in China’s interest and would lead to fewer of these spillovers and less discontent among their trading partners.

Ryssdal: You’ve been around the IMF for a very long time, Mr. Lipton. Have you ever seen anything like this?

Lipton: No, not in my lifetime. I mean, the truth is that there have been phases of trade disputes. I mean, when I was in the Clinton administration, there was a dialogue between the United States and Japan about Japanese trade practices. But I’d say that the difference is that we have a global economy that’s at a much more fragile point where the uncertainty coming from this subject along with the other issues in the world, you mentioned Brexit and there are many others, are together contributing to a fragility, to a slowing of trade. And this comes at a moment where we really need to be supporting the continued growth in the global economy and be very careful about anything that might tip the world into recession.

Ryssdal: I wonder if, perhaps, Americans are a little blasé about, as you say the fragility of the global economy, because you look around here and things are nominally good, right? Jobs, wages, consumer confidence, and even though [Federal Reserve Chair Jerome] Powell came out the other day and said, you know, the downside risk is global, and as you’ve been saying, global risk, are we just kind of whistling past the graveyard in this country?

Lipton: I think you made an important point. The United States economy is strong. I mean, the unemployment rate hasn’t been this low for a very, very long time. Wages are growing. Business and consumer confidence is strong. The U.S. economy is strong. But as Chair Powell pointed out, you know, that when you look at the global economy, it is more sluggish, and we are all in the same boat. The global economy is still very interconnected. So one has to, and I think this goes for all central banks, all central banks have to be now taking into account and weighing the internal and the, you know, global factors when they make decisions.

Ryssdal: Let me change gears for you for a second and take you sort of a bigger picture, beyond the macro that we’ve been talking about. This is the 75th anniversary this year of the International Monetary Fund. You gave a speech over in Paris a couple of weeks ago talking about threats to multilateralism and how the IMF has to adapt. How do you adapt when things are changing literally by the hour, at least on the American side, and multilateralism is to some degree threatened?

Lipton: Well, it’s true. I think there are doubts about whether cooperating in the international setting is more appropriate or less appropriate now. Many countries where there are winners and losers are more focused on domestic policies than on continuing to abide by international rules of the game. I mean, our institution was set up to promote global growth and stability and to make sure that all countries can gain through interconnectedness. I think it’s still a very important goal. We’ll not see the poorer countries in the world have a chance to catch up and have their living standards converge unless we all keep working together. So the answer, though, is that we need to help countries like the U.S. and Europe, where there are winners and losers, where there is a sense of being aggrieved by inadequacies in the global system, we need to help them figure out domestic policies that can address equal opportunity, create better sources of growth and do so without interrupting the globalization, the integration that’s been so important for pulling people out of poverty around the world. We also need to rethink the international rules of the game where they are inadequate, where they are genuinely leading to disruptions or permitting disruptions that will lead to resentments.

Ryssdal: Would you say you’re hopeful that we —

Lipton: I’m very hopeful. I mean, if you think about the International Monetary Fund, I mean, we were set up, as you pointed out, 75 years ago to deal with a fixed exchange rate system in the world. We’ve never had a Bretton Woods 2, and yet, we’re an international institution that has dealt with the Latin American debt crisis, the collapse of communism and the need to transition, you know, 25 countries from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union into capitalism. We’ve dealt with financial sector crises and the Asian crisis, and we’ve helped the world make its way through the global financial crisis. So, you know, I think we do change pretty well. We have to hit the pitch that’s thrown, and sometimes it’s a curve ball. But I am hopeful that — and when I say “we,” I mean, we are an organization with 189 member countries, member countries that are dedicated to trying to find ways to work together for mutual gain, and I think that that’s been a tremendous success over our 75-year history.