Credit scores can help determine where you live, your interest rates on loans and credit cards and even how much you pay for car insurance.

Credit scores can help determine where you live, the interest rates you’re charged on loans and credit cards and even how much you pay for car insurance. The algorithms that generate these scores have been developed over decades, and how well someone can manage their score can influence a big part of their financial life.

A whole industry is built around monitoring and managing credit scores, and ad campaigns from the 2000s and onward popularized the idea of trying to navigate the nuances of the algorithms as part of keeping personal finances healthy.

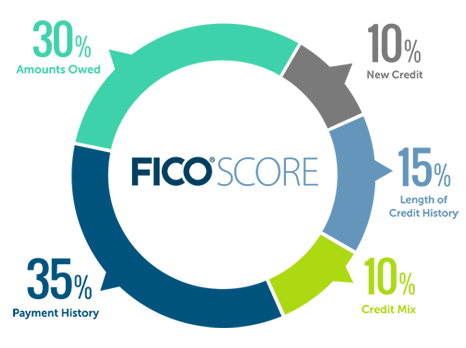

Credit scores range from the 300s to the mid-800s, depending on which company is calculating. And most people have several scores. The most popular is the FICO score.

“I think of the FICO score as an algorithm, a highly predictive algorithm,” said Ethan Dornhelm, who leads research and analytic development for FICO. “It’s one we develop from millions of anonymized credit reports. And we take this algorithm and deploy it at the credit bureaus.”

Credit bureaus like Experian, Equifax and TransUnion, which collect information about how you manage your debt.

“That will be information such as what are the past loans that you took out,” said Manju Puri, a finance professor at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University. “The credit cards, your lines [of credit], were you late? Did you default? All this information is taken in and packaged into a credit bureau score.”

As far as algorithms go, the ones that score credit tend to be relatively simple, said FICO’s Dornhelm.

“If I had a consumer’s credit report in front of me, I could actually calculate their FICO score by hand within 10 minutes or so,” he said.

And after decades of consumer education, many people feel like they generally know how to navigate the algorithm — even if not consciously.

Laura Ericksen, a retired academic adviser in Edina, Minnesota, said years of paying her bills on time and being careful with credit has kept her score “securely above 781.”

“It gave me a better rate when I bought my house. So it costs me less money to live. And I’m able to live in a nicer neighborhood than I would if I’d had a higher interest rate and had to spend less money on a house.”

Even though she’s pretty settled and comfortable, with no plans for upcoming major purchases, Ericksen said she still stays on top of her numbers because they affect other parts of her life as well.

“I just watch my credit scores because it affects my interest or my rate on my [auto] insurance … you get the best rate if you have a good score. “

In addition to FICO, there are other credit-scoring models, such as the VantageScore, and individual banks and lenders often have their own teams of data scientists and their own algorithms. Different models will assign varying levels of importance to components of a consumer’s credit report, which is why people can have multiple scores.

“The whole access to formal credit markets has typically relied on having a credit bureau score,” said Duke University’s Manju Puri. “And so people who have thin credit histories or thin credit files, they have trouble … getting a mortgage or other things because you don’t have a score.”

And that can create, or exacerbate, economic inequality, said Aaron Klein, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Klein led a panel in late 2021 examining whether credit scoring should be improved — or eliminated.

“Most people who failed to pay back a loan do so because of an exigent circumstance, like a medical catastrophe, a death in the family, a divorce or a job loss. These things are not necessarily well-modeled by whether or not you were late on a bill in the past,” Klein said.

Plus, Klein is concerned about credit scores and algorithms designed around the ability to pay back a debt creeping into other parts of the economy — as with the car insurance example.

“My car insurance rate was lowered, despite a less-than-stellar driving record, because I had good credit,” he said.

Toward the end of the 2000s, a series of ads about a hipster musician with bad credit helped popularize the idea of regularly checking your credit report.

The gaming YouTube Channel “Shameless Nerd” has an 8½-minute video tracing the story of the ads and what happened to the musicians involved.