How high’s the bar when it comes to suing an amusement park?

How much wiggle room does the law give us to make dumb decisions and still seek compensation?

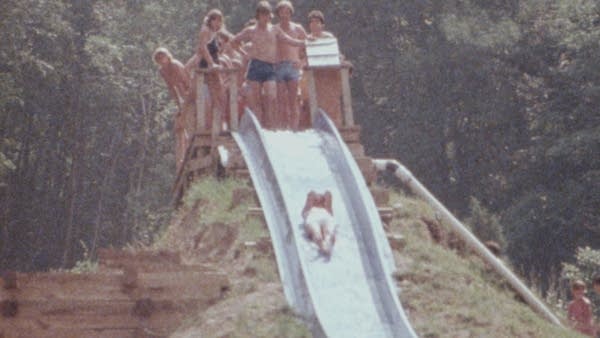

Our Econ Extra Credit series focuses on one documentary film a month with Marketplace themes. (Sign up for our newsletter here!) This month, we’re diving into “Class Action Park,” about an infamous and now defunct amusement and water park in New Jersey that took a lot of skin and bones — and some lives — before it went out of business in the mid-’90s.

Action Park’s marketing leaned into the idea that it might be dangerous, and we’ve been looking at the money lessons, especially lessons in legal liability. It’s a masterclass in tort law and a reminder that while the conduct of the operators of a theme park or ski slope matters if something happens, your conduct matters, too. To learn more, “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio spoke with Keith Hylton, a professor of law at Boston University. Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: So one of the things that emerges, partly from the documentary we watched but also from a book that was written by the son of the park’s then-owner, is that when someone complained that things had gone wrong, if they’d gotten hurt, a park official would talk to them quite quickly, very often, and find out, “So what were you doing at the time?” Does it matter in this situation if the park goer had been horsing around?

Keith Hylton: Oh sure, it does matter. I mean, every state has a notion of contributory negligence in their basic tort law. So if you’re horsing around — and to put in a non-technical way — horsing around too much, you might trip over the line and a court might find you guilty of contributory negligence. You’re allowed to make mistakes, of course, but there’s a certain point at which you can take it too far.

Contributory and comparative negligence

Brancaccio: I don’t know if you’ve been over to the American Museum of Tort Law, but one of the things I learned was that there was a time when if you contributed at all to the mishap, you’re out of luck, you couldn’t get any damages. But then there was a case, at some point, where this notion of, even if you are partly to blame you might be eligible for some kind of redress.

Hylton: Right. The harshest doctrine, which is known as “contributory negligence,” which gives you zero, if you’re guilty as the plaintiff of any negligence at all or substantial negligence. Then many states have developed a doctrine known as “comparative negligence.” And what that does is it gives you a share of the damages based on the degree to which your fault contributed to your own injury. So you can get something, under the comparative negligence regimes, you can get something for your damages, even though you’ve been guilty of contributory negligence yourself. So the harshness of the contributory negligence regime has been lessened quite a bit in a number of jurisdictions. But we still have a number of jurisdictions that have the harsh contributory negligence rule still in effect.

Brancaccio: Generally speaking, though, how much room do we have under the law to make knuckleheaded decisions but then still seek compensation?

Hylton: That’s an interesting question. And I don’t know if any courts have laid out really a general set of bright-line rules on that question, because at bottom, the question that courts ask is something known as the “reasonable person standard.” But to get quickly to your question, I guess I’d say that there are certain accidents, there are certain types of inadvertence, carelessness that would be permitted under the reasonable person standard, because it’s understood that not everyone is perfect all the time. There’s a certain point at which you crossed the line and a court would say, “That’s just too far. You know, that’s too much carelessness on the part of the plaintiff. And so we just can’t give the plaintiff a full award.” Again, in a comparative negligence state there would be some percentage of the full loss and in a contributory negligence state, the court would give the plaintiff zero. But even in the harshest contributory negligence regimes, courts have made some allowance for inadvertent, little mistakes. You know, failures to have your guard up all the time. Those things courts have looked over and juries have ignored and allowed the plaintiff to still collect damages.

Brancaccio: Right, because in the context of a water park or a theme park, you wouldn’t expect a young patron to be flawless all the time. In other words, you don’t need any seat belt for that ride because everyone will just settle in and sit there nicely. That seems a stretch. So there seemed to be like there might be a duty on the part of the park to have a seat belt to rope down the potential knuckleheads.

Hylton: That’s right. And I would say, depending on the ride, again — all of these cases depend on their specific facts — but depending on the ride, you know, you could say failure to wear a seatbelt is an obvious case of contributory negligence. And that would lead to some loss in the recovery and perhaps, you know, being set at zero in some states. But again, all of this really depends on what happened and going back to this, what I referred to before as the reasonable person standard, you know, would a reasonable person behave as the plaintiff did under the conditions that the plaintiff faced at the time?

What about when someone’s acting unreasonable?

Brancaccio: You should see this crazy park and the people who often would go to it. As depicted in the documentary and other sources, some people weren’t reasonable. They went there for the danger, you know, they didn’t go with the idea that they would never leave and that they would die, but they were hoping for things to happen to them. Which in a sense, seems almost unreasonable to those of us who didn’t go to the park and are looking in. You can see the subjectivity of that standard a little bit.

Hylton: Right. And your comment brings up another standard in the law, and that’s known as “assumption of risk.” And so if you go to a park and the dangers are open and obvious, and you walk right into those dangers, knowing what you’re getting into, then a court might say, “Well, that’s something that’s maybe worse than a contributory negligence, that’s something we’ll call ‘assumption of risk.’ ” And the assumption of risk rule is a bit harsher than contributory negligence, because once the court finds that you assumed the risk, then most courts say, “Well then your damages are zero.” You know, it gets sort of complicated in trying to look at the relationship between assumption of risk and contributory negligence across all the jurisdictions. But assumption of risk is something that’s generally a bit harsher for the plaintiff. And so you have a number of cases in which people go into amusement parks and get on a ride and get hurt, and the court says, “Well, the dangers that affected you are open and obvious and therefore you assumed the risk of danger.”

Brancaccio: You’re really helping me understand this, because the movie depicts one of the rides, it was called the “Alpine Slide.” It was like some kind of luge run from hell. And you’d hurdle down this thing, but you supposedly had control of the little sled you were sitting on. And people wouldn’t slow it down, it would go fast, and people would get hurt. And there’s this tension there, right? Because you’re being told to be in control of this thing. And there’s a reputation that also went with that ride, people knew that people would get hurt and they would go on it anyway. It helps explain one of the reasons this place wasn’t sued out of existence, it went out of business for other reasons.

Hylton: Right. With the assumption of risks doctrine, courts do require generally something more than just a reputation. I mean, most of the cases involve instances where the dangers were open and obvious, where someone could see them very easily. And not obscure, not a kind of danger that when you’re sitting outside of the ride and you’re looking you don’t see it, but once you get on the ride, then you notice, “Oh, you know, this is more dangerous than I realized.” So assumption of risk does generally require dangerous hazards that you can see and understand pretty well, just observing the ride. And so certainly, the one that you’re talking about sounds like it could easily subject the plaintiff to an assumption of risk charge. And then, as I said before, that’s distinguishable from the claim that, you know, whether you assume the risk or not, you just didn’t take the kind of care that you should have taken for your own safety.

The teachable moment

Brancaccio: I’m getting the lesson here that if I go to a theme park or a ski slope, I should behave myself and follow the rules. Because if something did happen and I felt that I was going to sue, that certainly would put me in a stronger position in a lawsuit if I had been not horsing about.

Hylton: For sure. You’re in the strongest position if you’ve taken reasonable care for your own safety and the danger that happens is something that wasn’t open and obvious and that you’d expect happening to anyone. Then you’re in a fairly good position as a plaintiff. And outside of those conditions, then you’re running into some troubles.